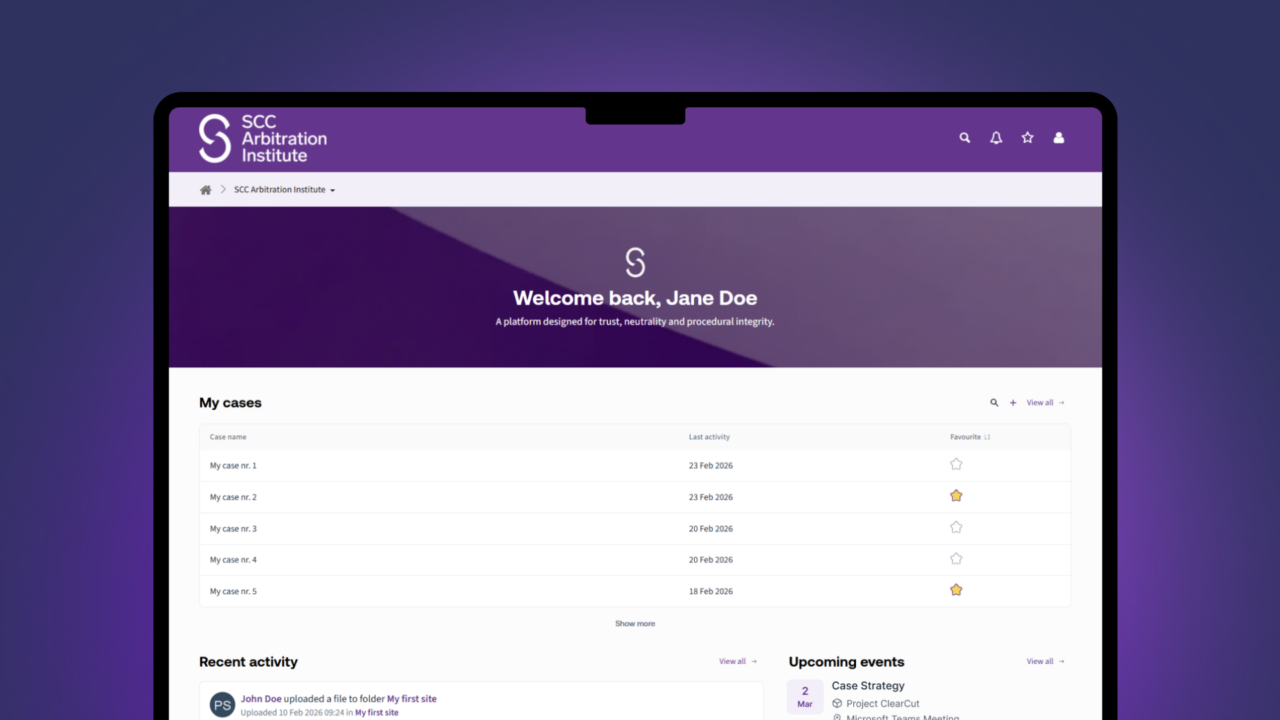

SCC Platform: Enhanced user experience with redesigned landing page

The new design provides a clearer overview, improved navigation and greater control for users managing their cases and documents. Together, these changes are intended to support a more efficient and user-friendly experience from the moment you log in.

Published

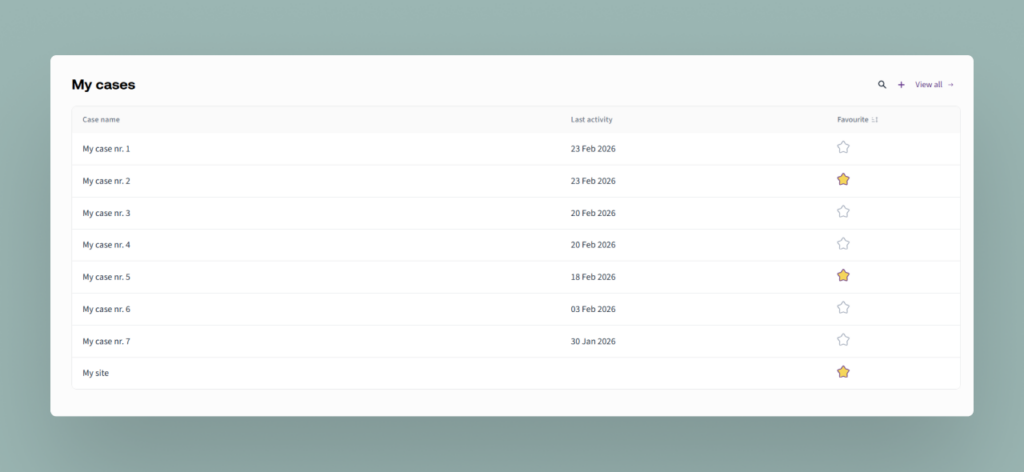

Cases front and centre

The redesigned layout prioritises what matters most: immediate access to cases. The new interface positions case information prominently in the starting view, enabling users to locate and access the correct case quickly and efficiently. This streamlined approach reduces navigation time and allows practitioners to focus on substantive work. Users can easily search, sort by most recent activity, or filter by favourites to quickly surface the cases they need.

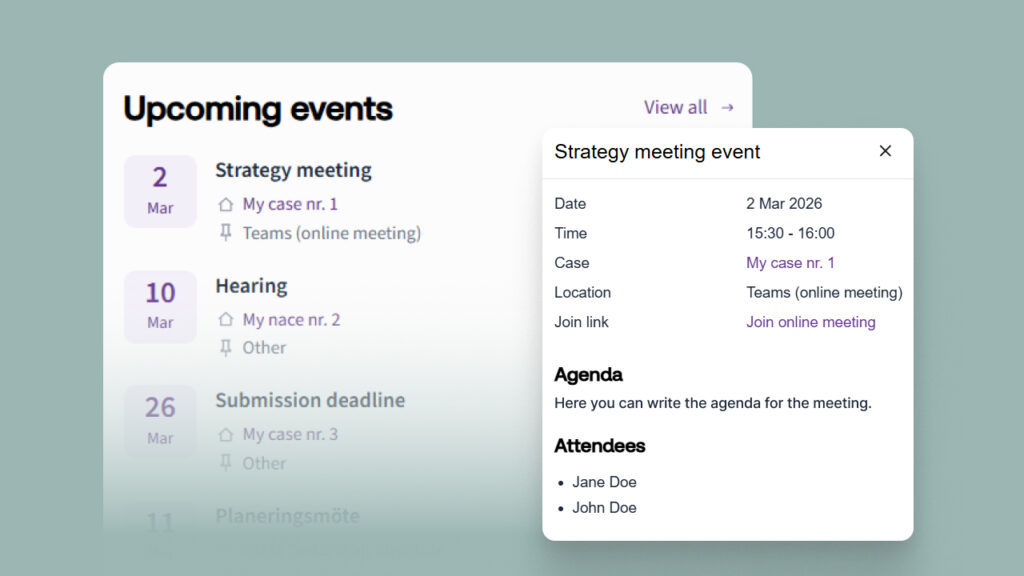

Stay ahead with upcoming events

A new upcoming events feature has been integrated into the landing page, giving users greater control over their schedules. The feature displays important deadlines and scheduled Teams meetings at a glance, ensuring that critical dates and virtual hearings remain top of mind.

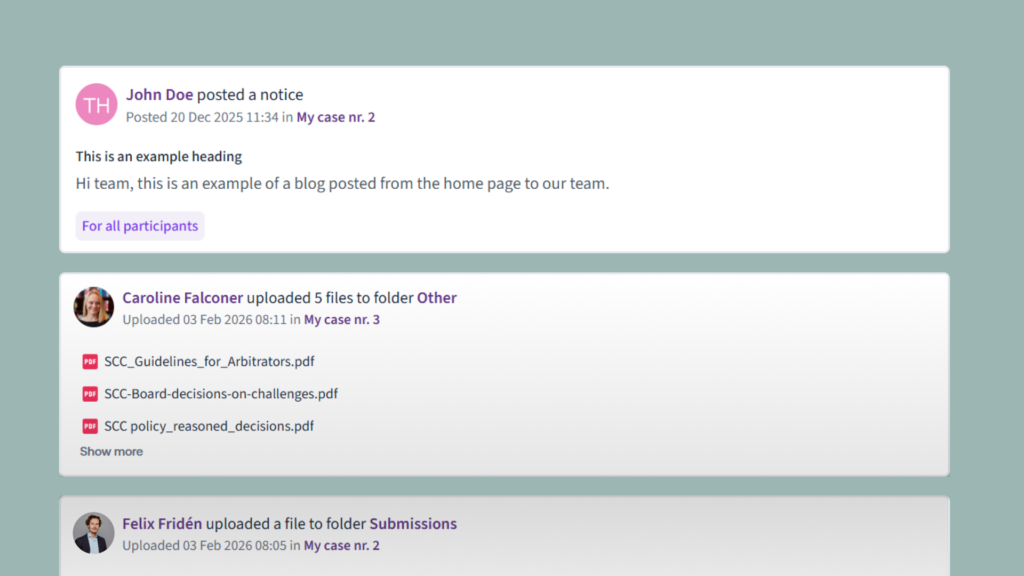

Refined activity feed with smart tag management

The activity feed has been upgraded with improved tag management functionality. Tags display intelligently, appearing only to relevant users, such as the SCC, ensuring that information reaches the right people without unnecessary clutter. This targeted approach to notifications helps users stay informed about developments that matter to their specific role in each case.

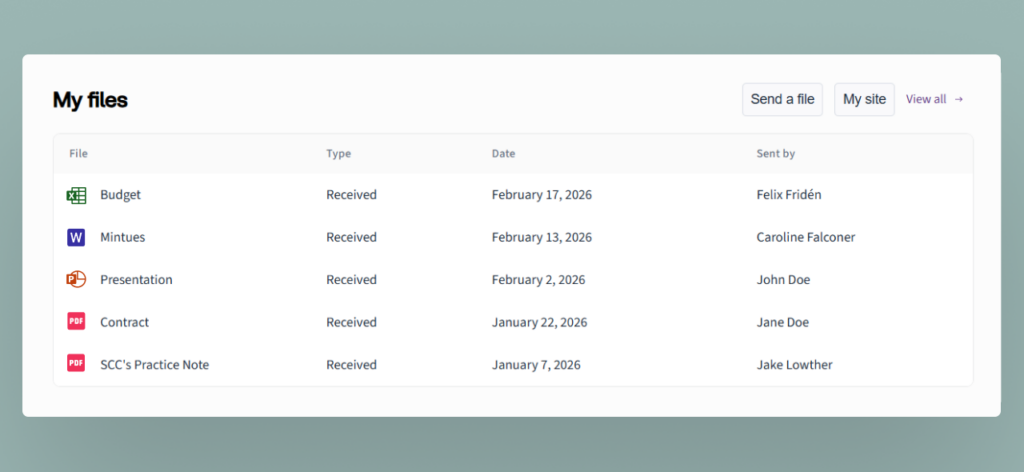

Improved “My files” experience

The “My files” feature has been redesigned with a refreshed layout that makes document management more straightforward. The new list view enables users to locate documents with greater ease, supporting the feature’s core purpose: facilitating the confidential sharing of documents within the secure SCC Platform environment.