Arbitrating for peace: Stockholm, SCC Arbitration Institute, and ISDS

Authors: Jake Lowther, Raoul J. Sievers, and Caroline Falconer1

Table of contents

Introduction

Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanisms are integral to the modern global foreign investment system, providing foreign investors with neutral fora to seek redress against host states if disputes related to their investments arise. These mechanisms are often characterized by high-value claims, complex legal issues, and the need for specialized expertise. The disputes typically involve intricate questions of international law, state sovereignty, and the protection of investor rights, which requires a neutral and specialized arbitration platform.

The SCC Arbitration Institute’s (SCC) reputation as a favourable forum for ISDS proceedings is underscored by its frequent inclusion in the arbitration clauses of international investment agreements (IIAs). These IIAs, which govern the treatment of foreign investments and provide a legal framework for addressing disputes, often designate specific arbitration fora to administer and resolve disputes between investors and states. Most IIAs take the form of bilateral investment treaties (BITs), though there are several multilateral investment agreements, such as the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT).

Since 1993, the SCC has been one of these preferred ISDS fora. To date the SCC has registered a total of 129 ISDS cases. In the past ten years alone, the SCC administered over 50 ISDS cases, with many initiated pursuant toarbitration clauses in key IIAs, including the ECT. In 2017, the SCC Arbitration Rules were revised, with specific ISDS provisions introduced for the first time. These introduced ISDS provisions regulate inter alia submissions by third parties and non-disputing treaty partners.2 This demonstrates the SCC’s ongoing commitment to ensuring a neutral and impartial process for the parties and other stakeholders in ISDS.

Furthermore, the SCC has been an active observer organisation at the UNCITRAL Working Group III sessions, which since 2017 has a broad man date to work on the possible reform of the ISDS system. In November 2024, the SCC also hosted UNCITRAL Secretary Anna Joubin-Bret to discuss inter alia the question of ISDS reform.3 The SCC is proud to contribute to the promotion of free trade and access to justice via the ISDS system of peaceful international dispute resolution.

This report is a partial update to the 2017 report “Investor-state disputes at the SCC” by Celeste E. Salinas Quero.4 This updated report analyses the SCC’s role in ISDS and examine how the inclusion of the SCC in ISDS clauses varies across different treaties and contracting parties. Through this analysis, the report highlights for investors and other arbitration practitioners where the SCC’s ISDS services have been and may be utilised, contributing to transparency in the ISDS system.

Purpose

The primary purpose of this report is to analyse the role of the SCC in arbitrating for peace and to examine how the inclusion of the SCC in ISDS clauses varies across different treaties and between contracting parties. By conducting this analysis, the report aims to highlight for investors and other arbitration practitioners where the SCC’s ISDS services may be and have been utilized, thereby contributing to transparency in the ISDS system. The report provides the users of ISDS a better understanding of the jurisdictions in which the SCC is used for ISDS disputes. Moreover, the statistics derived from publicly available sources address some of the perceived problems with ISDS, including its alleged pro-investor bias at the expense of state sovereignty.

As an update to the 2017 report, this report will also provide updated statistics and identify trends in ISDS cases administered by the SCC.

Methodology and material

Methodology

The data underlying this report was obtained in part from the SCC’s database, taking into account the SCC’s strict confidentiality obligations under the SCC Rules. Data for a more detailed analysis of the ISDS disputes administered by the SCC has also been obtained by examining the IIAs publicly available on the UN Trade and Development (UNCTAD)’s Investment Policy Hub5, and in particular the IIAs’ respective dispute settlement clauses.

Material – types of dispute settlement clauses

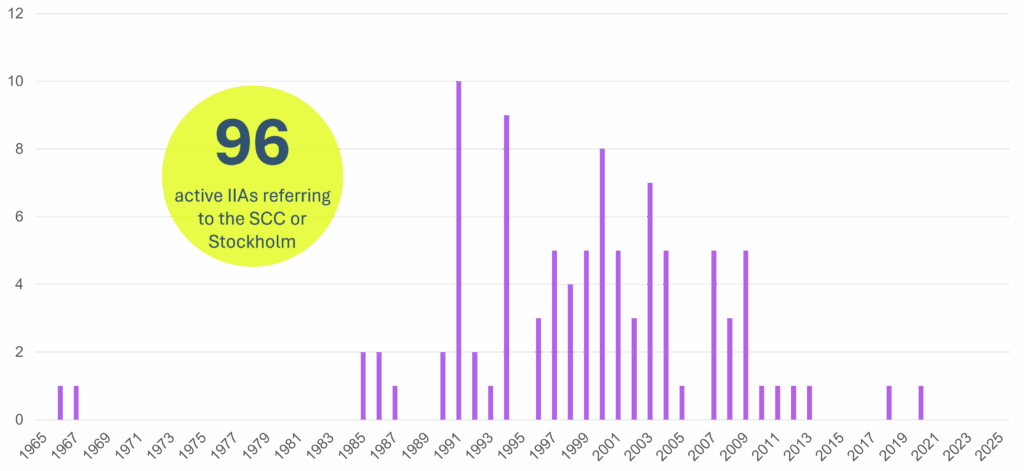

Out of the IIAs listed on the UNCTAD’s database, 288 agreements refer to either the “SCC” or “Stockholm”, with the earliest BIT dating back to 1965. Of these, 96 IIAs which refer to either the “SCC” or “Stockholm” are still in force as of March 2025 and were therefore considered in this report.6 Terminated IIAs have not been considered. Based on the wording of the IIAs, four different types of dispute settlement clauses emerge:

Alternative: Clauses under which the SCC is one of the institutions that may administer the dispute. For example:

“In the event that an investor elects to submit the dispute for resolution to international arbitration, the investor shall further provide its consent in writing for the dispute to be submitted to […] an arbitral tribunal constituted pursuant to the arbitration rules of any arbitral institution mutually agreed upon between the parties to the dispute, [where the SCC is one of the agreed upon arbitral institutions].” 7

Supportive: Clauses under which the SCC has a supportive role in the process, such as appointing arbitrators or providing inspiration for resolving the dispute according to SCC Rules. For example:

“In case the abovementioned deadlines are not honored, then each Party to the dispute may request the chairman of the arbitration panel at the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce to make the necessary appointments.” 8

Ad hoc or SCC: Clauses under which parties may decide to either use the SCC or ad hoc arbitration as a method of dispute resolution. For example:

“If the dispute cannot be settled amicably through negotiations for a period of five months starting from the date of receipt of the written request of any party to the dispute resolution through negotiations such a dispute may be submitted at the choice of the investor to […] an ad hoc arbitral tribunal in accordance with the Arbitration Rules of the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL); or the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce.” 9

Alternative seat: Clauses under which Stockholm is listed as one of the potential seats for arbitration. For example:

“Venue of arbitration shall be the Hague (Holland) or Stockholm (Sweden).” 10

Material – legal systems

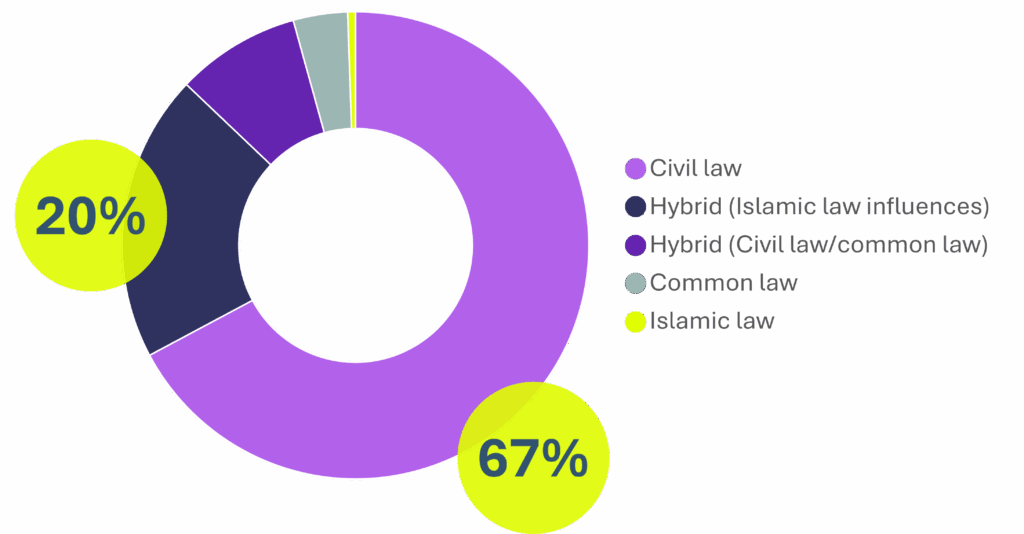

In terms of legal systems, we divided the agreements into four categories: civil law, common law, Islamic law, and hybrid legal systems. With regard to the hybrid legal systems, we note that some systems have drawn inspiration from both civil and common law traditions while others developed a distinct system often in conjunction with Islamic law principles. The hybrid category captures legal systems that do not fit neatly into either pure civil law, pure common law or pure Islamic law jurisdictions and tracks the respective influences. In particular, the hybrid law jurisdictions with Islamic law influences are often also influenced by both common and civil law. As a result, some of these jurisdictions may be counted more than once in the statistics on the distribution of legal systems.

To determine which legal systems are involved in the IIAs that mention the “SCC” or “Stockholm”, we examined the number of active IIAs of each country. To assess which legal systems are more likely to use the SCC, we have counted each IIA as having two legal systems – one for each party. For example, if there is a BIT between the United Kingdom (common law) and France (civil law), it would be counted once for common law and once for civil law. The total number of BITs reflected in the distribution of legal systems is therefore higher than the actual number of active BITs.

Analysis of active IIAs

Fewer ratifications of BITs

Currently, there are 96 active IIAs that refer either to the “SCC” or “Stockholm”. It should be noted, that a considerable number of dispute settlement clauses referring to the SCC were terminated in 2022 when the European Union (EU) terminated all BITs between its member states in response to the Court of Justice of the European Union’s (CJEU) judgment in Slovak Republic v Achmea (Achmea).11 We note the termination of 31 intra-EU BITs referring to the “SCC” or “Stockholm” for the resolution of disputes between January 2019 and August 2022.

Most of the active BITs that refer to the “SCC” or “Stockholm” were signed between 1990 and 2009. This trend mirrors a global trend of states moving away from policies promoting free and open trade, including the ISDS system.12

Legal systems

Among the BITs that mention either the “SCC” or “Stockholm” in their respective dispute resolution clauses, 67% are linked to a party from a civil law jurisdiction with another 9% of agreements connected to hybrid systems influenced by civil law principles.13 This emphasizes the SCC’s historically strong standing in continental Europe, the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), and the People’s Republic of China – all civil law jurisdictions.

Another 23% of BITs referring to the “SCC” or “Stockholm” are connected to parties from common law jurisdictions or jurisdictions influenced by common law principles. Of this 23%, 19% are considered hybrid jurisdictions with common law influences and include Cyprus, South Africa, Kuwait, Eritrea, the Seychelles, and Sri Lanka. The remaining 4% can be classified as pure common law jurisdictions. Examples of these jurisdictions include the UK, Malaysia, Ghana, and Hong Kong.

According to our analysis, 20% of BITs are related to Middle East and North Africa (MENA) jurisdictions classified as hybrid jurisdictions characterised by Islamic law influences. Examples include Qatar, Algeria, Egypt, Lebanon, Libya, Turkmenistan, and Jordan. One further BIT was linked to a party that is understood to maintain a pure Islamic law jurisdiction, namely the Islamic Republic of Iran.

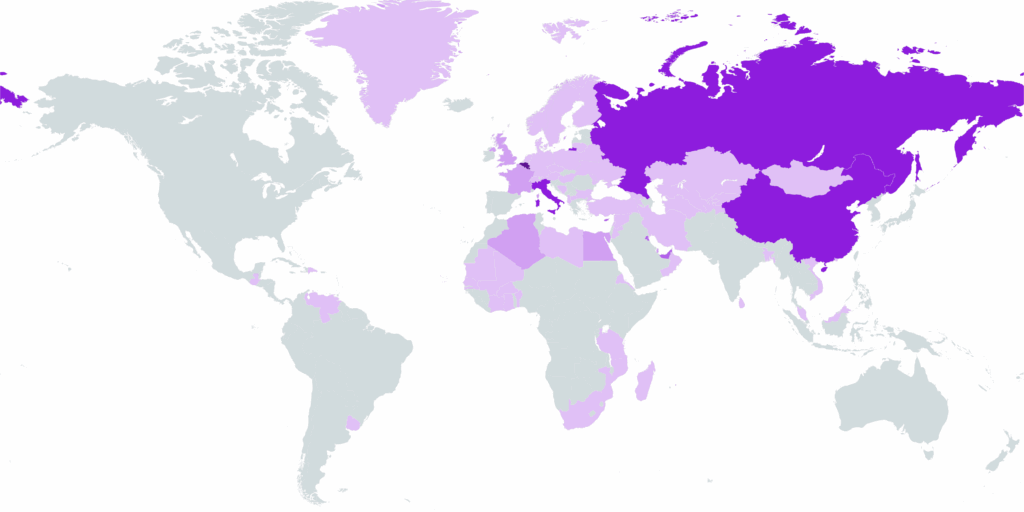

According to the UNCTAD data, a total of 71 different jurisdictions have concluded BIT’s referring disputes to the “SCC” or “Stockholm”. The fact that 18 BITs referring to the “SCC” or “Stockholm” were signed by states from non-civil-law jurisdictions suggests that confidence in the SCC as an institution and Stockholm as a neutral seat is not influenced by the legal traditions of the parties involved.

We observe that the majority of BITs which use clauses referring to the “SCC” or “Stockholm” include at least one of four states which frequently designate the “SCC” or “Stockholm” as a dispute resolution forum in their BITs, namely the Belgium–Luxembourg Economic Union (BLEU) (17 BITs), Russia (15 BITs), Italy, and the People’s Republic of China (both 12 BITs). These jurisdictions are involved in 56 of the 95 active BITs referring to the “SCC” or “Stockholm” (59%).

Meanwhile, the SCC’s growing popularity in legal systems typical for the MENA region is also reflected in the total number of BIT’s involving jurisdictions from the region with Kuwait (8 BITs), the United Arab Emirates (UAE) (7 BITs), Algeria, and Egypt (both 5 BITs) ranking among the ten countries with most BITs referring to the ”SCC” or ”Stockholm”

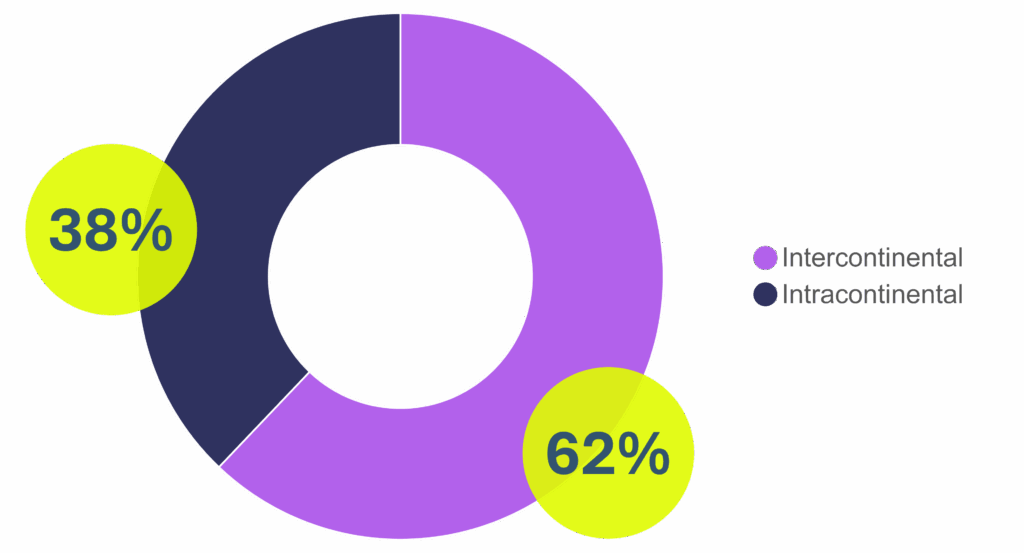

Intercontinental BITs

Notably, most of the BITs that refer to the “SCC” are intercontinental agreements, i.e., between states from different continents. A minority of BITs concerned parties located on the same continent.14 A total of 59 active BITs areintercontinental (62%), as opposed to 36 intracontinental agreements (38%).

15 BITs involve states from Europe and Africa, while four BITs between parties in Africa and Asia refer to the “SCC” or “Stockholm”. Finally, two BITs involve countries from Europe and North America while another two BITs referring to the “SCC” or “Stockholm” involve parties from Europe and South America.

The largest group of IIAs that refer to the “SCC” or “Stockholm” were concluded between parties from Europe and Asia (28 BITs). This confirms the SCC’s historic status as a dispute resolution hub for East-West disputes, with many IIAs involving either the People’s Republic of China or Russia. This role first developed in 1977, when the SCC was included into the Optional Arbitration Clause for Use in Contracts in trade between the US and the Soviet Union. In 1984, the SCC and the China Council for Promotion of International Trade entered into a cooperation agreement, which cemented the SCC’s position as a bridge between East and West.

Intracontinental BITs

There are a number of intracontinental BITs between parties from Asia (10 BITs) and Africa (6 BITs) respectively. However, most intracontinental BITs referring disputes to the jurisdiction of the SCC or providing for Stockholmas the seat involved European countries (21 BITs). As mentioned, this excludes 31 intra-EU BITs which were recently terminated in response to the CJEU’s Achmea jurisprudence.15 Furthermore, it should be noted that seven intracontinental BITs currently in force involve parties who are EU member states and candidates for EU membership respectively.16 For now, these BITs remain unaffected by the EU’s jurisprudence as at least one of the parties is not a member state of the EU.

BITs involving Nordic jurisdictions

Given the prominence of the SCC and Stockholm in ISDS, it should come as no surprise that Nordic jurisdictions also appear in the UNCTAD data. This is primarily the case in respect to IIAs between Nordic jurisdictions and China and Russia.

Denmark has entered into three BITs referring to the “SCC” or “Stockholm”. Two of these are intercontinental BITs in which the SCC has a supportive role in the process. The third is the Denmark-Russian Federation BIT (1993) in which the SCC is the only arbitral institution that may administer the dispute.

Finland has entered into one intracontinental BIT in which the SCC has a supportive role in the process.17

Norway has entered into two BITs referring to the “SCC” or “Stockholm”. One is an intracontinental BIT in which the SCC is the only arbitral institution that may administer disputes.18 The second is an intercontinental BIT in which the SCC has a supportive role in the process.19

Interestingly, Sweden has entered into two intercontinental BITs with African jurisdictions referring to the SCC.20 Both of these IIAs contain clauses providing for the SCC as an alternative dispute resolution forum.

The role of the SCC and Stockholm where they are designated

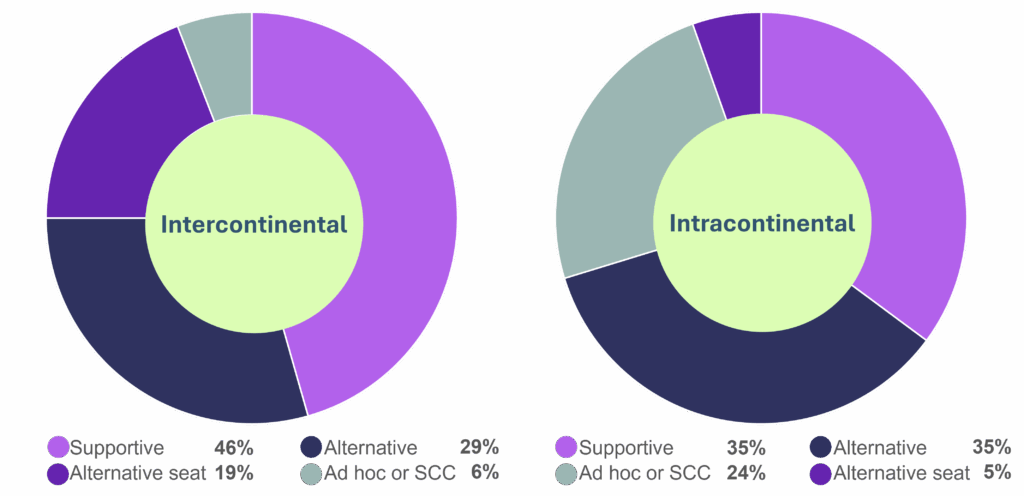

Across the IIAs that refer to the “SCC” or “Stockholm” for dispute resolution services, 46% provide for the SCC as a supportive authority (44 IIAs) while 36% designate the SCC as an alternative dispute settlement forum (34 IIAs). Stockholm is designated as an alternative seat in 16% of these IIAs (15 IIAs). Notably, another 14% of BITs include clauses under which the parties are given the choice to either initiate ad hoc arbitration or submit their dispute to the jurisdiction of the SCC as the only available institution (13 IIAs).

The IIAs currently in force predominately designate the SCC as a supportive authority followed by a significant share of BITs providing for the SCC as an alternative dispute resolution forum. The two alternatives form the basis for over 80% of IIAs which refer to the SCC. IIAs providing for Stockholm as an alternative seat of arbitration are less common.

Interestingly, in intracontinental agreements, the SCC is as commonly designated as an alternative dispute settlement forum (13 BITs) as it is as supportive authority (13 BITs). In contrast, intercontinental BITs refer to the SCC far more frequently as a supportive authority (31 BITs) than as an alternative dispute resolution forum (20 BITs). In a similar manner, BITs providing the parties with the choice between either ad hoc arbitration or institutional arbitration administered by the SCC are significantly more frequent among intracontinental (24% of intracontinental BITs) than among intercontinental agreements (6% of intercontinental BITs).

Disputes

SCC’s data

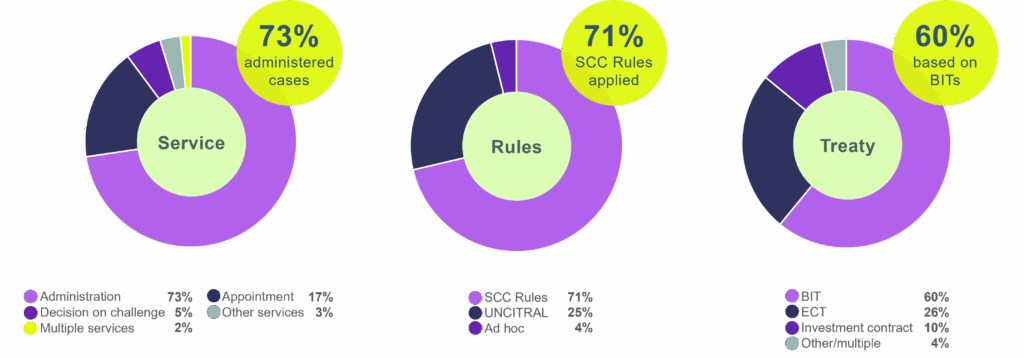

As mentioned above, the SCC has registered a total of 129 ISDS cases since 1993. Three of these cases are pending as of 22 May 2025. Of these 129 cases, 94 were administered by the SCC (73%) while the SCC acted as appointing authority in another 22 disputes (17%). In the remaining cases, the SCC was designated to decide on challenges or to provide other services such as fund holding. In the majority of cases, a BIT provided the basis for consent to arbitrate (60%) followed by disputes referred to the SCC under the ECT as well as under individual investment agreements. In most disputes administered by the SCC, the SCC Rules applied (71%). The remaining proceedings were conducted either under the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules or were ad hoc proceedings with no predetermined set of rules.

Comparison with the 2017 Report

Since the 2017 report,21 the SCC has registered another 37 ISDS cases. As in the cases analysed in the 2017 report, the SCC was designated as the administering institution in the vast majority of these disputes (73%). Other services included decisions on challenges, appointments of arbitrators, and fund holding. The SCC Rules formed the procedural framework in most cases (70%) followed by the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules and a smaller number of ad hoc arbitrations with no predetermined set of rules.

While BITs continue to provide the basis for consent to arbitrate in most disputes (54%), we note an increase in the share of disputes referred to the SCC through individual investment agreements compared to the statistics shared in our 2017 report. Finally, we also observed a slight increase in the amounts disputed in investment cases. In our 2017 report, we calculated an average amount in dispute of EUR 332 million.22 Since then, the SCC administered a volume of roughly EUR 7 billion claimed in investment disputes, accounting for an average of EUR 358 million per case.

In the period following the 2017 report, the SCC’s administration of investment disputes has faced some challenges arising inter alia from the termination of over 30 BITs following Achmea, several withdrawals from the ECT, and the CJEU’s jurisprudence in Republic of Moldova v Komstroy.23 However, the present caseload analysis reveals a high degree of resilience and adaptability. For instance, an increasing number of cases have been referred to the SCC on the basis of extra-EU BITs and individual investment agreements. The trends that emerge from this analysis demonstrate that the SCC remains a leading and important forum for ISDS cases.

Data listed on UNCTAD

With reference to the SCC’s strict confidentiality obligations under the SCC Rules, in this section we have restricted the following in-depth analysis of ISDS disputes to the publicly available information available on the UNCTAD’s Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator.24 The statistics in this section therefore do not contain any confidential information derived from the SCC’s digital case management platforms, unless clearly stated otherwise. As a result, the following analysis concerns 56 publicly listed disputes arising in connection with IIAs administered by the SCC. In this regard, our analysis focuses on two questions:

(i) which IIAs are the most active in terms of the number of disputes arising in connection with them, and

(ii) how successful are investors in disputes administered by the SCC.

To the first question, we assessed the listed caseload with regard to the active IIAs under which they arose. From this, we can observe the following:

- Notably, of the 56 ISDS cases administered by the SCC as listed by UNCTAD, exactly half of the cases arose in connection with the ECT, with the other half arising in connection with a BIT. This is in contrast to the SCC’s own data, which reveals a much larger proportion of BIT cases overall, as discussed in section 5.1.

- Nine of these ECT disputes listed by UNCTAD were initiated by investors bringing claims against Spain arising out of a series of energy reforms undertaken by the government affecting the renewables sector.

- Other respondent states UNCTAD frequently lists in ECT disputes administered by the SCC include Ukraine, Poland, and Italy.

- Six further cases listed on UNCTAD arose out of investments made under the Moldova-Russia BIT (1998), all of which saw Moldova on the respondent side.

- Moreover, UNCTAD lists multiple cases of UK investors bringing proceedings against state respondents under both the Czechia-United Kingdom BIT (1990) as well as the Russia-United Kingdom BIT (1989).

- We further note that another 12 listed disputes were initiated under BITs which are no longer active.

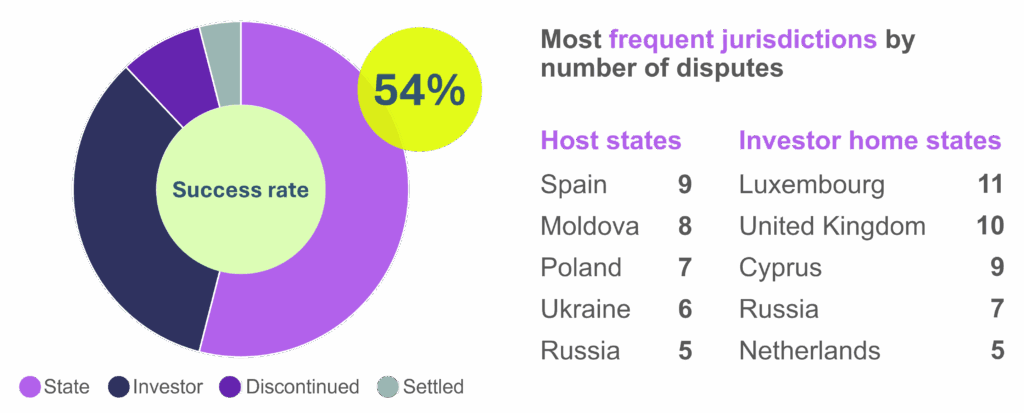

In respect to the second question, we observed that ISDS inter alia frequently faces criticism for being overly investor friendly. This led us to examine the success rate of investors in IIA disputes listed by UNCTAD as administered by the SCC. Notably, in the 50 listed and concluded cases administered by the SCC (this excludes the six cases UNCTAD classifies as “pending” as per 22 May 2025), there was a favourable decision for the state in 27 of the 50 proceedings (54%).25 By contrast, according to UNCTAD’s database investors were successful only in 17 cases administered by the SCC (35%). In two disputes, UNCTAD reports that the parties ultimately agreed to settle (6%), while another four cases were eventually discontinued (8%). It should be noted that this assessment excludes six cases listed by UNCTAD as currently pending before the SCC.

Among the most reported respondent states, UNCTAD lists Spain as leading the list (9 cases), followed by Moldova (8 cases), Poland (7 cases), Ukraine (6 cases), and Russia (5 cases). Except for Moldova, all of these jurisdictions are also included among the ten most frequent host states in all ISDS cases registered on UNCTAD between 1987 and 2023.26

Concluding remarks

In summary, this report has analysed the SCC’s role in arbitrating for peace and examined the inclusion of the SCC and Stockholm in ISDS clauses across the IIAs.

In highlighting where the SCC’s ISDS services have been and may be utilised, the report contributes to greater knowledge and transparency in the ISDS system. Moreover, by building on the analysis of the 2017 report, the SCC demonstrates its ongoing commitment to providing a neutral and efficient dispute resolution forum. This report’s new insights offer investors, states, and arbitration practitioners a clearer understanding of the jurisdictions in which the SCC is a trusted forum.

An analysis of the data addresses some of the perceived issues with ISDS, such as its alleged pro-investor bias. Moreover, it can be concluded that the SCC continues to have a significant role in ISDS and peaceful dispute resolution. The SCC and Stockholm’s inclusion in numerous, predominately intercontinental IIAs, from the Nordics to jurisdictions located across five continents, reflects its reputation as a trusted independent and neutral forum across continents and regions. The effect of the CJEU’s jurisprudence in Achmea has been the termination of the majority of European intracontinental BITs. However, the SCC and Stockholm maintain their importance, referred to in 96 IIAs between states from all over the world. This is further confirmed by the steady flow of complex, high-value investment cases administered by the SCC each year. This report therefore reinforces the significance of the SCC and Stockholm in the global investment treaty arbitration landscape.

Notes

1 The authors are grateful to Raffaela Isepponi, Erik Erba Stenhammar, Chloé Heydarian, and Gaurav Majumdar for their invaluable contributions to this report.

2 See SCC Arbitration Rules, Appendix III.

3 See, e.g., SCC, “UNCITRAL-secretary on reforming Investor State Dispute Settlement” (19 November 2024) ; Sievers, R., Kluwer Arbitration Blog, “SCC Arbitration Institute Explores Security for Costs in International Arbitration” (17 November 2024) .

4 Salinas Quero, C. E., “Investor-state disputes at the SCC” (SCC, 2017).

5 UNCTAD, Investment Policy Hub (updated as of 31 July 202 4).

6 Previously, 126 IIAs referred to either the “SCC” or “Stockholm”.

7 Art. 9(3)(c) BIT between Bosnia and Kuwait.

8 Art. 7(2) BIT between Algeria and Jordan.

9 Art. 9(2) BIT between Russia and Venezuela.

10 Art. 8(5) BIT between China and Qatar.

11 CJEU, Judgment of 6 March 2018, Case No. C-284/16.

12 As mentioned before (cf. under section 3.3), hybrid law jurisdictions with Islamic law influences are often also influenced by both common and civil law. As a result, some of these jurisdictions will be counted more than once in the statistics on the distribution of legal systems and the following percentages should not be understood as totalling 100%

13 As mentioned before (cf. under section 3. 3), hybrid law jurisdictions with Islamic law influences are often also influenced by both common and civil law. As a result, some of these jurisdictions will be counted more than once in the statistics on the distribution of legal systems and the following percentages should not be understood as totalling 100%.

14 In cases where a country spans two continents (e.g., Russia or Turkey), the agreement is considered intra-continental if the other party is from either one of the continents.

15 To provide clarity for the international investment treaty arbitration community, the SCC in its policy adopted in October 2024 clarified that, in the absence of party agreement in investment treaty cases, the SCC Board will determine a seat outside the EU. This policy confirms the SCC’s obligations under the SCC Rules to make every reasonable effort to ensure that any award is legally enforceable. See SCC Policy: Deciding the seat in intra-EU investment arbitrations administered under the SCC Rules as adopted by the SCC Board on 16 October 2024. https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/wp content/uploads/2025/01/scc_policy_seat_of_arbitration_2024_1.pdf.

16 Namely, the Albania-Cyprus BIT (2010), the BLEU-Bosnia Herzegovina BIT (2004), the Cyprus-Republic of Moldova BIT (2007), the BLEU-North Macedonia BIT (1999), the BLEU-Republic of Moldova BIT (1996), the BLEU-Ukraine BIT (1996), and the BLEU-Georgia BIT (1993).

17 Finland-Russian Federation BIT (1989).

18 Norway-Russian Federation BIT (1995).

19 China-Norway BIT (1984).

20 Côte d’Ivoire-Sweden BIT (1965); Madagascar-Sweden BIT (1966).

21 Salinas Quero, C. E., “Investor-state disputes at the SCC” (SCC, 2017) .

22 Salinas Quero, C. E., “Investor-state disputes at the SCC” (SCC, 2017) , p. 6.

23 CJEU, Judgment of 2 September 2021, Case No. C-741/19.

24 UNCTAD, Investment Policy Hub, “Investment Dispute Settlement Navigator” (updated as of 31 July 2024).

25 This includes cases in which an Arbitral Tribunal found liability but no damages.

26 Spain is the third most common host state in ISDS cases registered on UNCTAD (56 listed disputes), Poland is in seventh place (37 listed disputes), and Ukraine and Russia share the tenth place (31 disputes) (UNCTAD, IIA Issues Note: Facts and Figures on Investor-State Dispute Settlement Cases, November 2024, p. 6).