Green technology disputes at the SCC Arbitration Institute

Author: Christoffer Coello Hedberg

Table of contents

Introduction

In August 2019, the SCC Arbitration Institute (the “SCC”) published a report titled “Green Technology Disputes in Stockholm” written by Andrina Kjellgren for the SCC (the “2019 Report”).1 The 2019 Report looked at commercial disputes involving green technologies registered by the SCC between 2014 and 2018, as well as investment treaty disputes concerning investments in the green technology sector registered by the SCC between 2012 and 2018.

The 2019 Report found that, parallel to a global rise in climate change litigation, the SCC had experienced an increase in commercial and investment treaty disputes involving green technology. According to the 2019 Report, the number of those disputes was expected to increase in line with the continued expansion of green technology, green investments and the transformation to a low-carbon economy. Considering the developments in climate action since then, this report follows up on the 2019 Report by analysing (i) whether the number of commercial disputes involving green technology and investment treaty disputes concerning investments in the green technology sector has increased in line with the 2019 Report’s predictions, and (ii) whether the nature and characteristics of the green technology cases, registered by the SCC since then, have changed.

Needless to say, the urgency of climate change and the need for a global green transition has not decreased since the 2019 Report. The Paris Agreement on Climate Change, adopted in 2015, remains one of the most important international climate agreements. It aims to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.2 A key measure for reaching these goals is climate mitigation, meaning human intervention to reduce sources, or enhance the sinks, of greenhouse gases (“GHG”).3 The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report (the “IPCC Report”), found that total GHG emissions continued to increase between 2010–2019 with annual average GHG emissions being higher in this period than in any previous decade.4

At the same time, the rate of growth of emissions was lower than the previous decade,5 while the cost of low emissions technologies, such as solar and wind power, had decreased, resulting in their increased deployment.6 The IPCC Report also found that policy packages have been effective in supporting low-emission innovations,7 and that the consistent expansion of policies and laws addressing climate change mitigation has helped avoid GHG emissions that would otherwise have occurred.8 Still, the IPCC Report found that, in the absence of immediate, rapid, and large-scale reductions in GHG emissions, the goal of limiting the global average temperature increase to 1.5°C or 2°C will be beyond reach.9

The urgency of climate change mitigation was also highlighted in a recent report by the United Nations Environment Programme (“UNEP”), which found that policies currently in place are projected to result in global warming well over 2°C over the twenty-first century and that economy-wide transformations are required to limit global warming to below 2°C.10 Another key measure for climate change action is adaption, meaning the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate change and its effects.11

Large investments in climate change mitigation and adaption are needed to accomplish a shift to low-carbon economies.12 This fact is reflected in the Paris Agreement, where parties undertake to make “finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse-gas emissions and climate resilient development”.13 The IPCC Report found that finance flows for climate change mitigation and adaption action increased by 60% between 2013/14 and 2019/20.14 According to a report published by United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (“UNCTAD”), international investment increased following the introduction of the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015, while strong acceleration occurred in 2021 with the total project value increasing to twice that of pre COVID-19 pandemic values.15 According to the same report, 94% of climate investments went towards mitigation actions rather than adaption measures.16 BloombergNEF confirms similar findings. According to its report, global investment in the low-carbon energy transition totalled USD 755 billion in 2021 which was an increase from USD 595 billion in 2020 and from USD 264 billion in 2011.17 According to the same report, the renewable energy sector attracted the most investments while the rate of growth of investments was biggest in the electrified transport sector.18

Since the 2019 Report, climate change litigation has continued to increase globally. A report published by UNEP considered the term “climate change litigation” to include all cases that raise material issues of law or fact relating to climate change mitigation, adaptation, or the science of climate change. The UNEP report revealed that as of 1 July 2020, at least 1,550 climate change cases had been filed in 38 countries. This means that the number of climate change litigation cases has nearly doubled since March 2017.19 As will be further elaborated upon in this report, the SCC has experienced a similar increase in the number of Green Technology Commercial Disputes.

Considering the threatening rate of climate change, increasing financial flows for climate action and the vast number of regulatory changes affecting existing industries, the arbitration community must also do its part in preventing and reducing the negative impacts of climate change. This is not only prudent from a moral point of view, but as acknowledged in the SCC Sustainability Commitment, which will be described below, end users of dispute resolution services put ESG and sustainability at the core of their businesses. As providers of dispute resolution services, the arbitration community should align with those requirements. To quote Lucy Greenwood’s article “The Canary is Dead: Arbitration and Climate Change”:

Against this background, this report follows up on the 2019 Report by examining commercial disputes and investment treaty disputes registered with the SCC between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022. In doing so, the report examines whether the trends discussed in the 2019 Report have continued during this period and whether any new trends are discernible. The report aims to provide a better understanding of how companies contributing to the green transition benefit from the use of the SCC’s dispute resolution services. As will be further elaborated upon below, this report’s findings support the view that the number of disputes involving such companies is increasing.

The SCC Arbitration Institute

Founded in 1917, the SCC’s mission is to facilitate trade and business by providing a neutral, independent and impartial venue for dispute resolution. The SCC changed its name from the Arbitration Institute of the Stockholm Chamber of Commerce to the SCC Arbitration Institute in November 2022.

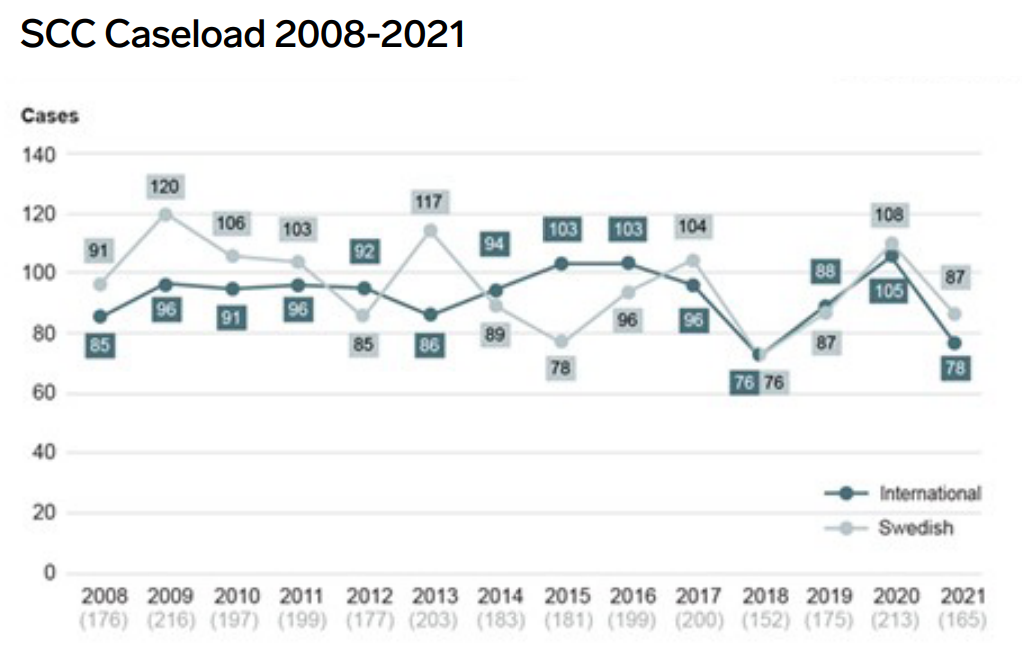

The SCC maintains different rules that are regularly updated in line with recent developments in arbitration and the needs of its users. The Arbitration Rules and the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations apply to the majority of SCC cases. The Arbitration Rules apply to approximately 60% of the cases registered by the SCC every year, while the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations apply to approximately 30% of the annual caseload. In 2021, the Arbitration Rules applied to 62% of cases and the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations applied to 30% of them. Parties from 43 different countries appeared in SCC administered cases in 2021.

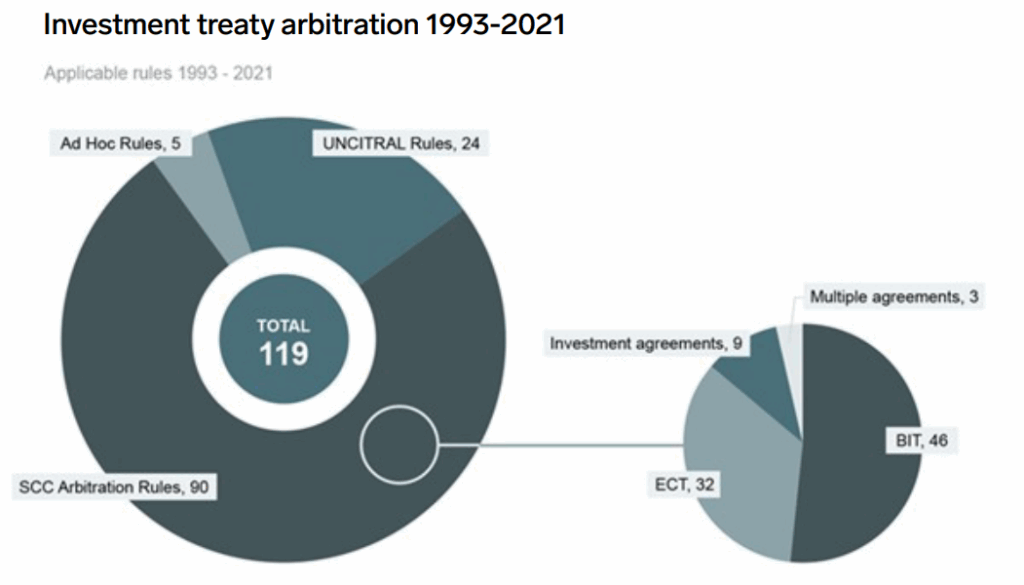

In addition to administering commercial arbitrations, the SCC is one of the leading international arbitral institutions administering disputes between investors and states based on investment treaties. To date, the SCC has registered 119 investment treaty disputes. The Arbitration Rules applied to 76% of those cases, with the majority being based on bilateral investment treaties (“BITs”) or the Energy Charter Treaty (the “ECT”). Sweden and the SCC are listed as a forum for investment treaty arbitration in 121 BITs, as well as in the ECT. Of these 121 BITs, 61 agreements provide that the Arbitration Rules are to apply to disputes arising from the agreement. The remaining 60 BITs nominate the SCC as an Appointing Authority under the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules or Sweden as the seat of arbitration.21

The SCC also maintains procedures for the administration of arbitrations under the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, the SCC Mediation Rules, and the SCC Rules for Express Dispute Assessment (the “SCC Express”). The SCC Express, adopted in 2021, provides an alternative form of dispute resolution designed to meet a specific need identified among arbitration users. The SCC Express is a consent-based and confidential process

which offer parties a legal assessment of their dispute within three weeks, for a fixed fee.

Since the 2019 Report, the SCC has closely examined its role in the transition to a low-carbon economy. As a result, the SCC recently launched the SCC Sustainability Commitment, which sets out the measures taken by the SCC to provide dispute resolution services in line with its users’ ESG and sustainability requirements.22

As set out in the SCC Sustainability Commitment, the SCC has taken measures to reduce its own carbon footprint by using a digital case management platform and encouraging carbon offsetting for arbitrators’ flights and reimbursing such expenses. The SCC has also facilitated virtual attendance at hearings and promoted online participation as an alternative to travel. Moreover, the SCC supports the Campaign for Greener Arbitrations as a signatory to the Green Pledge and has implemented the Green Protocols into its operations.23

Further, the SCC provides efficient tools for the resolutions of climate- related disputes. The need for climate action is urgent and climate related disputes require efficient resolution in order for companies to keep up with the pace of the climate transition and focus their resources on business and climate goals. As noted in the 2019 Report, arbitration has an important role to play in putting power behind the words of commercial contracts in the green technology sector and the protection granted under investment treaties. Efficiency and expeditiousness are two of the SCC Rules’ cornerstone principles and they are enshrined in Article 2 of the Arbitration Rules and the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations. They require that “the SCC, the Arbitral Tribunal and the parties shall act in an efficient and expeditious manner”. The principles are reinforced by the fact that the SCC considers the arbitral tribunal’s efficiency and expeditiousness when determining the costs of the arbitration.24 A similar mechanism applies to the arbitral tribunal’s apportionment of costs incurred by the parties and the costs of the arbitration between the parties. In that regard, the arbitral tribunal shall consider each party’s contribution to the efficiency and expeditiousness of the proceedings.25

Further, the SCC Rules provide for flexible proceedings which can be tailored to accommodate the typically complex and international nature of climate related disputes. Other aspects that affirm the suitability of arbitration as an instrument for resolving such disputes include the fact that (a) arbitration allows for disputes to be resolved by arbitrators possessing relevant qualifications and expertise, and (b) arbitral awards are internationally enforceable under the 1958 New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (the “New York Convention”). As one of the most successful international treaties with more than 160 parties, the New York Convention not only makes international recognition and enforcement of arbitral awards possible, but contributes to arbitration’s suitability in resolving climate related disputes—especially those involving cross-border investments and international elements.

Introduction and methodology: SCC Green Technology Commercial Disputes

This part of the report focuses on commercial green technology disputes. Like the 2019 Report, it presents the basic facts and figures of the commercial green technology disputes registered with the SCC between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022.

For the sake of consistency, this report uses the same definitions used in the 2019 Report. Thus, the term green technology is defined as “any process, product or service that reduces negative environmental impacts in support of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change”.

The cases examined in this report are disputes where one or both parties used a type of green technology as part of its main business activity (“Green Technology Commercial Disputes”). All SCC cases registered between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022 were reviewed in order to identify the Green Technology Commercial Disputes. As in the 2019 Report, cases where the language of the arbitration was not English or Swedish were excluded.

The above delimitation helps determine the extent to which the parties use the SCC’s services to resolve green technology disputes specifically. However, a few other reservations were implemented when applying the definition. One such reservation was whether disputes involving energy companies, which are oftentimes large companies with operations in different energy sectors, spanning both renewable energy and fossil fuel, should be included in the report. For this report, disputes involving energy companies as parties have only been included where such companies operated within the renewable energy sector in the dispute’s underlying commercial context. Another reservation was whether investment companies focusing on investments in green technology or other businesses working with climate action, should be included in the report. For the sake of consistency, such disputes were not included unless another party to the dispute used a green technology as part of its main business activity.

Further, the above delimitation excludes certain processes, products and services which could be classified as “green” but do not reduce the negative environmental impacts in support of the Paris Agreement in an apparent way. An example of technologies which thus fall outside of the scope of this report is technologies for water purification for environmental and health purposes. It could be argued that such technologies are a part of climate change adaption efforts. For the sake of consistency however, such technologies were excluded from this report.

The numbers of Green Technology Commercial Disputes

Number of cases

Using the methodology described above, the SCC registered 61 Green Technology Commercial Disputes between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022, accounting for 9% of the total cases registered by the SCC during this period.

This marked a significant increase in the number of Green Technology Commercial Disputes compared to the timeframe examined in the 2019 Report. There, the SCC registered 31 cases between 2014 and 2018, accounting for 3% of the total number of cases registered during that period.

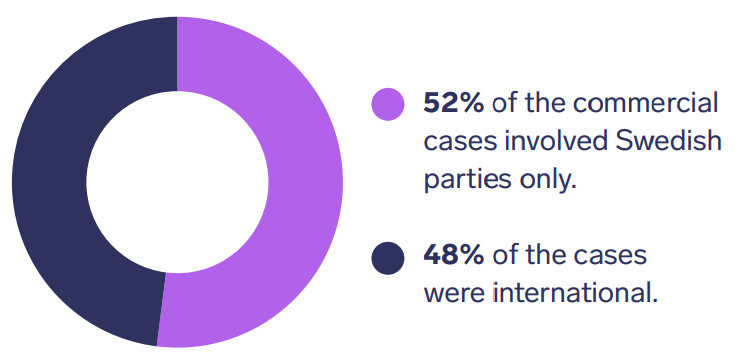

The parties

The 2019 Report found that 62% of the disputes were domestic disputes, involving only Swedish parties. The remaining 38% were international disputes, where one of or both parties to the dispute were non-Swedish. The international disputes accounted for a larger share of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes identified in this report, with 52% of the cases involving only Swedish parties while 48% of them involved non-Swedish parties.

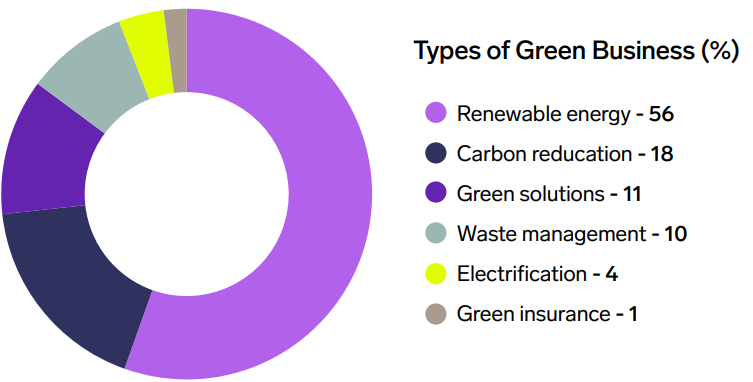

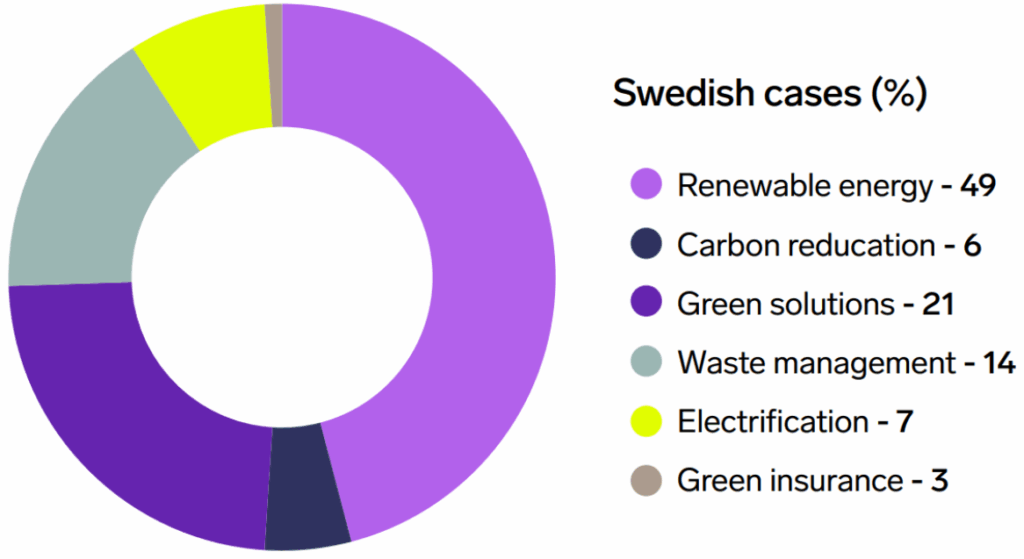

The 2019 Report identified eight business sectors to which the disputing parties belonged, showing that green technology companies pursued business in diverse sectors. In the 2019 Report, 61% of the parties who appeared in the identified cases pursued business activities in the renewable energy sector.

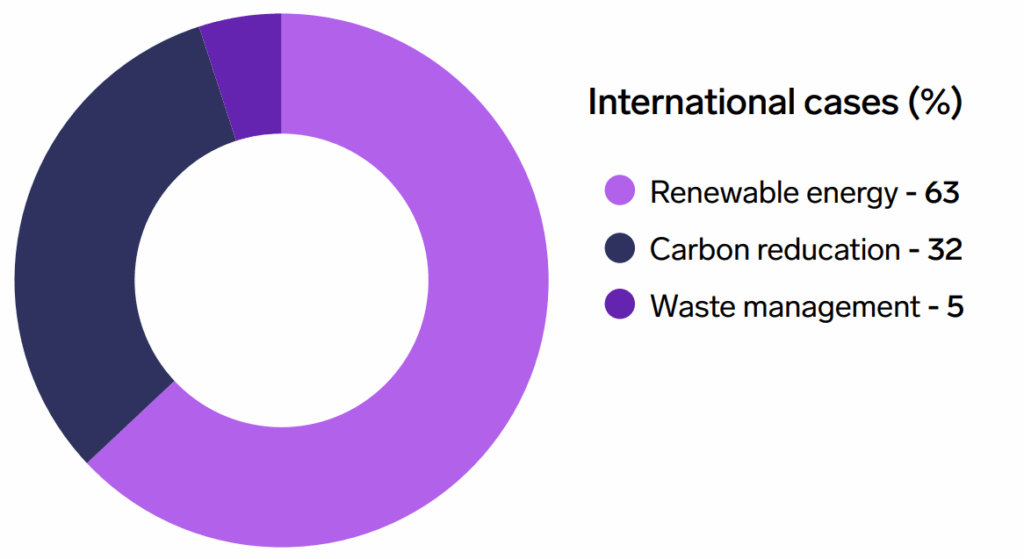

The renewable energy sector was the most common sector identified for the parties appearing in Green Technology Commercial Disputes in this report as well, with 56% of parties pursuing their main business activity within this sector. The percentage of parties pursuing business in this sector was higher in international cases than in Swedish cases.

Compared to the 2019 Report, a larger share of parties had carbon reduction as their main business activity. Such parties pursued a wide range of green business activities but were usually the proprietors of technological solutions designed to reduce the carbon emissions of industries or consumers. Parties pursuing their main businesses within the electrification sector, including various solutions to electrify processes and make the supply of electricity greener, were involved in Green Technology Commercial Disputes. Considering the ongoing efforts to electrify economies and the increasingly large investments being made in this sector, as implied by the BloombergNEF report mentioned above, it would be reasonable to assume that the number of disputes involving parties in the electrification sector will continue to increase. The business activities of some parties have been classified as green solutions, which include various sustainable processes and innovations. Other parties pursued commercial activities within the waste management sector and the green insurance sector.

Using the terminology set out in the introduction section of this report, the vast majority of the parties involved in the Green Technology Commercial Disputes pursued activities aimed at climate change mitigation rather than adaption. This is perhaps unsurprising considering that most climate investments are directed towards mitigation efforts. Further, the Green Technology Commercial Disputes identified involved both parties innovating and developing technologies with the potential to mitigate climate change and parties in more traditional sectors, such as construction and energy, which are undergoing significant transformation in response to increased regulatory demands.

Parties from 20 different countries appeared in the Green Technology Commercial Disputes examined in this report. Swedish parties appeared the most frequently. Besides private companies, individuals and state entities were also represented in the case load. As for the cases with state parties, these disputes primarily arose in relation to infrastructure or energy projects aimed at reducing GHG emissions.

Nationality of parties

- Belgium

- Brazil

- Canada

- Chile

- Denmark

- Estonia

- France

- Ireland

- Lithuania

- The Netherlands

- Poland

- Romania

- Russia

- Sweden

- Tajikistan

- United Kingdom

- USA

- Germany

- Iceland

- Italy

The disputes

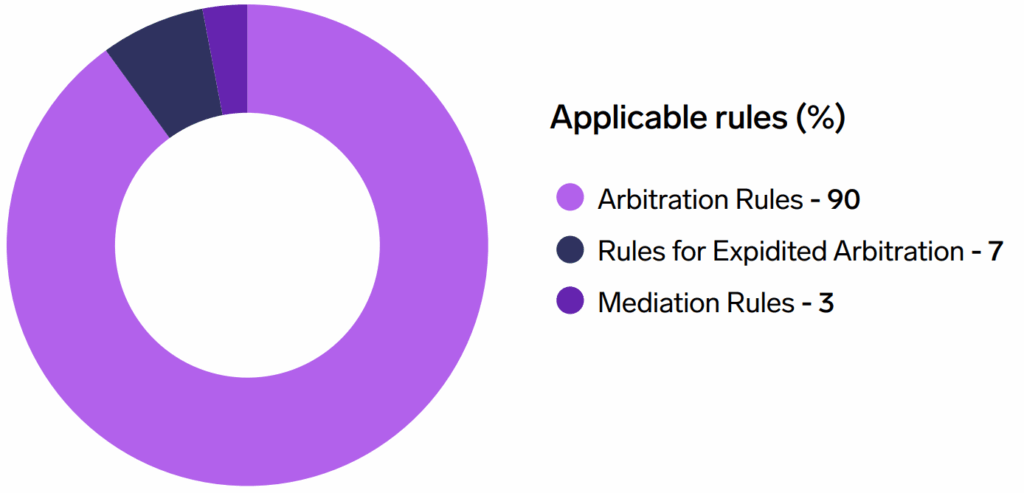

The Arbitration Rules applied to 90% of the cases, which is an increase compared to the cases examined in the 2019 Report. Meanwhile, the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations applied to 7% of the cases while the Mediation Rules applied to the remaining 3% of cases. The SCC Express Rules did not apply in any cases. As for the mediation cases, the disputes related to alleged deficiencies in construction works performed on renewable power plants and factories.

Overall, the amounts in dispute ranged from EUR 10,000 to EUR 95,508,426 with an average amount in dispute of EUR 9,989,403. The amounts in dispute in Swedish cases were generally lower than in international cases. In Swedish cases, the amounts in dispute ranged

from EUR 10,000 to EUR 58,324,113, with an average amount in dispute of EUR 5,877,824. In international cases, the amounts in dispute ranged from EUR 30,349 to EUR 95,508,426 with an average amount in dispute of EUR 14,526,317. This range effectively demonstrates the multi-faceted nature of climate related disputes. The Green Technology Disputes involved both disputes arising out of smaller contracts, such as agreements entered into by companies developing green innovations, and large contracts, such as construction agreements for renewable power plants.

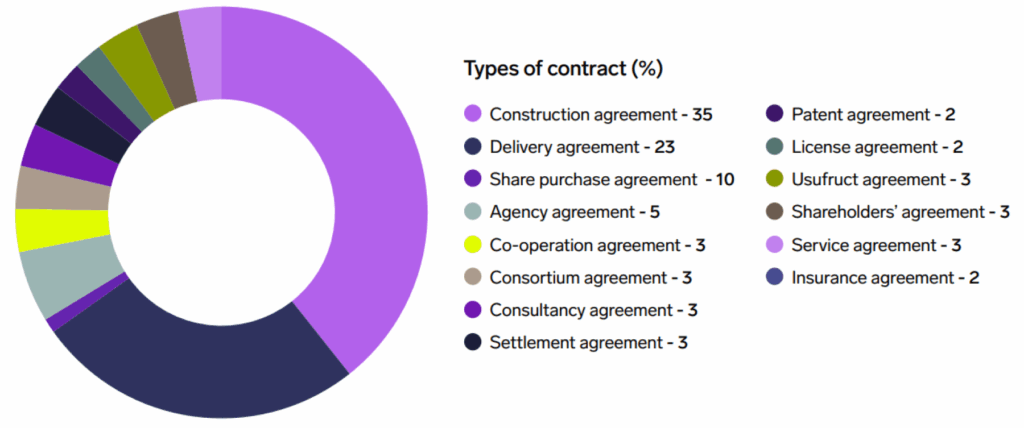

The Green Technology Commercial Disputes examined in this report all arose out of various commercial agreements. The most common types of contracts in these cases were construction agreements and delivery agreements.

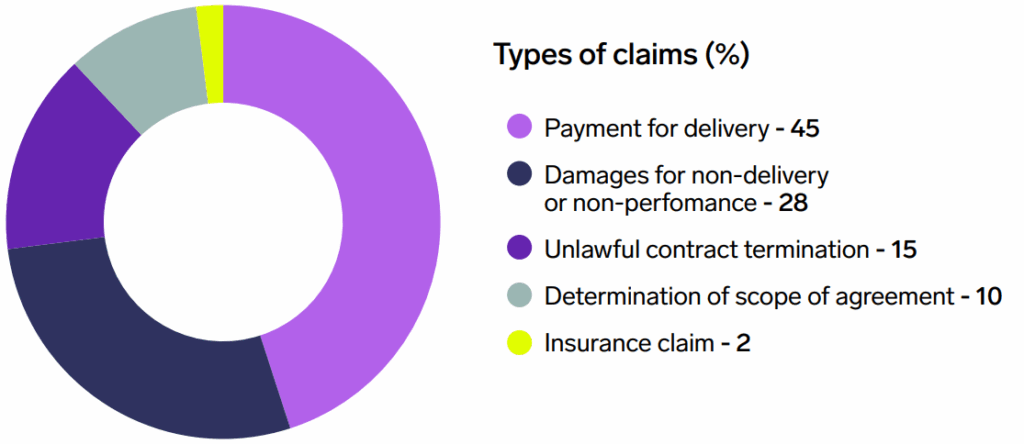

As for the types of claims presented in the Green Technology Commercial Disputes, most claims were categorised as claims for delivery or claims for damages due to non-delivery or non-performance.

Payment for delivery is given a wide meaning and includes all claims for specific performance based on contractual obligations to pay for goods, services or otherwise fulfil contractual payment obligations. The typical claims belonging to this category concerned payments for the goods or services of a green technology company. Other examples include claims for payment for delivery of biofuel, a claim for payment of a settlement amount agreed under a settlement agreement between a green technology company and one of its former employees, and a claim for payment of royalties to be paid for the sale of a green technology product.

Damages for non-delivery or non-performance typically included claims for damages due to unsatisfactory work, delay, or deficiencies in delivery. This category also includes other cases of alleged non-performance. One example is a case where the dispute concerned the amounts payable under a guarantee by various parties to a consortium agreement. The distinction between these categories is primarily made with reference to the nature of the claimant’s claim. It is not unusual for cases to include both claims for payment for delivery and claims for damages for non-delivery or non- performance. In some of the construction disputes relating to renewable plants for example it was not unusual for the claimant to claim payment for performed works, and for the respondent to present counterclaims based on costs incurred due to unsatisfactory work.

As for the claims categorised as determination of the scope of agreement, these mainly included declaratory claims requesting the arbitral tribunal to declare that contractual provisions applied to certain facts or events. An example of such claims is a dispute regarding a contract for the supply of renewable energy, where the claimant alleged that events which led to unfairness had occurred and had triggered a review clause in the contract. Another example was a dispute regarding whether an increase in the price of biofuel had been lawful under the contract. Yet another example was a dispute where the claimant requested the tribunal to determine that a license for a green technology only applied to certain industrial facilities. Another case illustrating the variety of claims in this category is a dispute concerning whether a green technology company was entitled to redeem the shares of one of its shareholders due to actions allegedly taken by the shareholder.

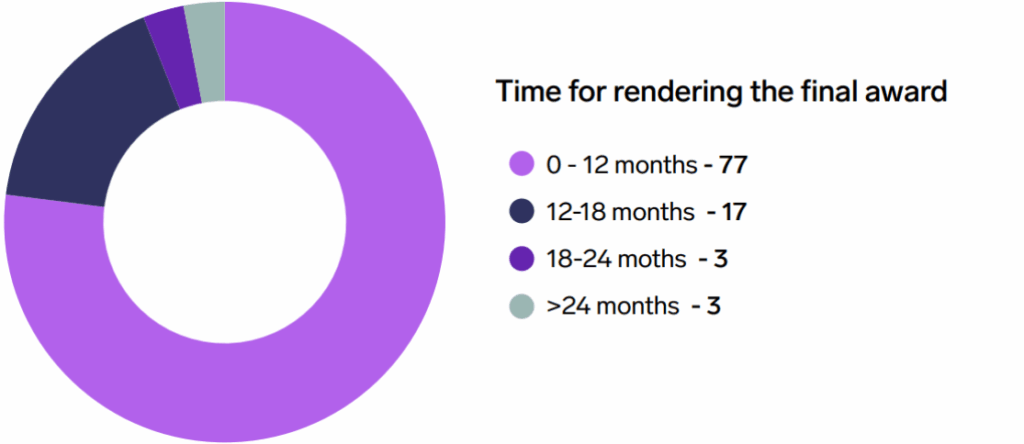

At the time of writing this report, final arbitral awards have been rendered in 31 Green Technology Commercial Disputes. The average time from the date of registration until the date that the final award was rendered in the Green Technology Commercial Disputes was ten months. The final award was rendered within 12 months in 77% of the cases examined in this report. This is notable when compared to the cases covered by the 2019 Report, in which the final award was rendered within 12 months in only 40% of cases. This is good news since one of the main advantages of arbitration is expeditiousness—something particularly important in Green Technology Commercial Disputes. However, it should be noted that a final award has not yet been rendered in 13 ongoing cases examined by this report.

The substance of Green Technology Commercial Disputes

Introduction

When discussing arbitration and climate change, investment treaty disputes are probably the first that come to mind given the interplay between investment and policy those cases typically involve. However, commercial arbitration certainly has a role to play in the green transition. Commercial disputes in relation to climate change can arise from a wide range of contractual relationships. Climate actions in the form of mitigation, adaption, and financing will generally rely on commercial contracts for their deployment, implementation, and performance. While some contracts may be entered into expressly in response to international climate agreements or policies, the majority of contracts will likely concern commercial obligations regarding projects, investments, or other activities which indirectly support climate action. This has indeed been the case for the majority of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes identified in this report. Some contracts are also entered into to adapt to the green transitions and requirements impacting specific sectors, such as the energy or construction sectors. A big share of the SCC case load already involves parties and contracts in those sectors, meaning that the number of Green Technology Commercial Disputes is only expected to increase.

In the 2019 Report, the examined cases were divided into three types based on the substance of the disputes: (1) disputes arising directly from or in connection with an international climate agreement or climate policy, (2) disputes that are technical in nature, and (3) non-technical disputes. The Green Technology Commercial Disputes identified in this report have been divided into the same categories.

It should be noted that the categories are broad, and that the substance of some Green Technology Commercial Disputes fit into multiple categories. For example, some of the disputes designated as technical disputes and non-technical disputes may be considered as arising in connection with climate policies. Such disputes involve disputes concerning the construction of renewable energy facilities with the express purpose of decreasing the fossil fuel energy share in the energy mix of the country where the renewable energy facility was to be constructed. Such construction projects are, at least to some extent, motivated by domestic or international policies on carbon reduction. However, for the purposes of this report only cases with a more express connection to climate policy have been included in the first category. Against this background, the vast majority of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes identified by this report did not arise directly in connection with an international climate agreement or climate policy. Rather, most Green Technology Commercial Disputes belonged to the other two categories.

Disputes arising directly from or in connection with international climate agreements or climate policy

International cooperation is generally perceived as an enabler for achieving climate change mitigation goals.26 The United Nations Framework Agreement on Climate Change, the Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement are still among the most important international legal frameworks concerning climate change. As explained in the 2019 Report, these instruments do not mention arbitration as a way to resolve disputes related to these instruments. However, arbitration can play an important role in achieving the objectives of these instruments by providing a neutral and efficient way to resolve disputes arising from commercial contracts aimed at realising the objectives of such instruments. Even though the parties to the above mentioned instruments are states and not private entities, their implementation depend on commercial projects involving private entities, such as the parties involved in the Green Technology Commercial Disputes examined in this report.

The 2019 Report identified two disputes falling into this category. One related to a project that aimed to implement the Joint Implementation Mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol. The other related to an Environmental Protection Agency penalty issued due to an alleged failure to transfer emission rights in time.

No disputes arising in connection with the Kyoto Protocol were registered with the SCC in the time period relevant to this report. However, cases with a connection to other international climate requirements were registered. One such case concerned a dispute regarding works performed in a factory to comply with the emission requirements set out in the Industrial Emissions Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council on Industrial emissions (integrated pollution prevention and control) (the “IED”). The IED is an EU directive that lays down rules on integrated prevention and control of pollution arising from industrial activities, as well as rules to prevent emissions and generation of waste.27 It should be noted that the IED covers industrial emissions other than GHG emissions, which are excluded from the directive’s scope.28

Further, obligations in line with those established for states under international climate agreements may be imposed on private entities in the form of national or regional climate policies. One such dispute was registered with the SCC in the time period relevant to this report. It concerned a waste management system regulated by national policies.

Disputes that are technical in nature

Many of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes identified in this report could be classified as technical in nature. As mentioned above, construction agreements were the most common contracts from which Green Technology Commercial Disputes arose. Consequently, and in line with the findings of the 2019 Report, the technical cases identified in this report predominantly concerned construction disputes, with most cases relating to renewable energy. Such disputes include the construction of power plants such as wind farms, biomass power plants, and hydro power plants as well as service and installation works performed on such plants. Some cases did not concern the power plants themselves, but rather facilities connecting power plants to national power grids. Typically, the claimants in the disputes were either contractors claiming payment for work performed or employers and owners of energy facilities claiming damages for alleged deficiencies in the performance of the works. The construction cases also included construction projects that were smaller in scale, such as a dispute concerning works performed by the claimant for the installation of solar panels on the respondent’s property.

Another type of technical Green Technology Commercial Dispute registered with the SCC in the time period relevant to this report concerned the delivery of components to be used in renewable energy facilities. In one example, the claimant alleged that components delivered by the respondent to a renewable energy power plant were defective. In another, the claimant claimed payment for the delivery of components designed to reduce a power plant’s emission.

This category also included disputes which did not concern construction or delivery of components but were nevertheless technical in nature. In one example, the claimant claimed payment for work performed in relation to the deployment of a test project for a product designed to generate renewable energy. The deployment was complicated by technical errors and the dispute concerned whether the respondent was entitled to terminate the agreement or was liable to pay the claimant for its work. Another example concerned the scope of intellectual property rights in a technology designed to reduce emissions.

A common feature in this type of Green Technology Commercial Disputes is the use of expert evidence by the parties. Such evidence mainly consisted of the views of technical experts. In one dispute concerning the cause of deficiencies in the fundaments at a wind farm for example, the contractor presented an expert statement to prove that the deficiencies were caused by design errors for which the claimant was not responsible. In another case regarding the installation of solar panels, both parties presented expert reports to support their views on whether the installations were correctly performed or not.

Under Article 34 of the Arbitration Rules, the arbitral tribunal may appoint experts to report on specific issues after consulting the parties. This provision was not utilised by the arbitral tribunals in any of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes examined in this report. However, tribunal-appointed experts are rather rare in SCC arbitrations.

Non-technical disputes

The rest of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes examined in this report may be classified as non-technical in nature. This classification covers a broad range of disputes. Like the cases identified in the 2019 Report, many Green Technology Commercial Disputes falling within this category concerned unpaid deliveries for goods or services delivered by or to green technology companies. Other examples concerned various contractual breaches, such as a dispute where the claimant claimed damages for losses caused by the respondent’s failure to nominate the agreed number of biomass deliveries.

Some of the non-technical disputes involved technical aspects, even though the substance matter of the overall dispute was not technical in nature. For example, one dispute concerned a contract for the supply of a component to a power plant designed to reduce GHG emissions. The claimant asserted that the respondent had not paid for units delivered according to the contract. Another example concerned a settlement agreement concluded in the wake of the purchase of wind power stations, where the wind turbine seller had allegedly failed to pay the buyer the compensation agreed to be paid for as long as the wind turbines produced insufficient power.

A few cases related to the use of a green technology developed by one of the parties. These cases included a dispute concerning royalties pertaining to a green technology as well as a dispute concerning alleged breaches of a co-operation agreement in terms of which the respondent undertook to provide the claimant’s green products to its end customers.

Finally, some cases concerned general corporate disputes involving green technology companies. One case, for example, concerned the termination of a partnership agreement for the production and delivery of solar panels. Another case concerned a consultancy agreement under which the claimant would provide financial consultancy services to a green technology company. Other cases of a general nature included post M&A-disputes regarding transactions of green technology companies or companies created for the purpose to operate renewable power plants and insurance disputes.

Procedural features in Green Technology Commerical Disputes

Use of efficiency tools under the SCC Rules

As mentioned earlier in this report, efficiency and expeditiousness are cornerstone principles of the SCC Rules, which are designed to enhance the efficiency of proceedings.

For less complex cases that do not require voluminous written submissions or oral hearings, the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations provide a way to settle disputes in a time efficient manner and at a lower cost. The Rules for Expedited Arbitrations applied to 20% of the cases examined by the 2019 Report. The Rules for Expedited Arbitrations applied to 7% of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes examined by this report. These cases mainly involved smaller businesses that had developed green solutions with small amounts in dispute.

The Mediation Rules were used in two of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes examined in this report. Both cases involved Swedish parties only. This is interesting since mediation has not yet gained a strong foothold in the Swedish market. Mediation can be an efficient form of dispute resolution for green technology companies wishing to avoid the time and costs associated with conventional forms of disputes resolution.

The same is true for the SCC Express, adopted in 2021. The SCC Express was not applied to any of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes. Considering that one of the main areas of application for the SCC Express is where parties want to preserve their commercial relationship and time is of the essence, the SCC Express could certainly benefit many Green Technology Commercial Disputes.

Besides the general emphasis on efficiency and expeditiousness, the SCC Rules also contain specific tools designed to enhance the efficiency of proceedings. These include rules for multi-party arbitrations such as provisions on joinder of additional parties, consolidation of cases and claims arising out of multiple contracts in a single arbitration. Some 34% of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes were multi-party disputes involving multiple claimants or respondents. Examples of such cases are disputes concerning renewable energy power plants, which will oftentimes include multiple parties due to the size and structure of such projects, post M&A-disputes, where the underlying transaction included multiple buyers or sellers, and corporate disputes involving multiple shareholders. In most of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes examined, the parties remained the same throughout the proceedings. In some cases, however, the abovementioned provisions were utilised. One such case concerned whether the respondent, which was a shareholder in a green technology company developing an environmentally friendly material, was entitled to redeem the claimant’s shares in the company. The case was consolidated with an ongoing SCC arbitration relating to the same company. Another example is a case where the SCC decided to grant a request for joinder. The dispute arose from a share purchase agreement concerning the transfer of shares in a green technology company. The parties agreed that guarantors, which had guaranteed the performance of the seller under the agreement, should be joined to the arbitration. In another case, which concerned the construction of a wind farm, the SCC denied a request to join a subcontractor to the dispute.

Besides multi-party provisions, the SCC Rules provide other tools to enhance the efficiency and expeditiousness of the proceedings. One example is Article 39 of the Arbitration Rules, which allows the arbitral tribunal to decide one or more issues of fact or law by way of summary procedure if requested by the parties.29 Summary procedure was not used in any of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes. The SCC Rules also contain provisions on the appointment of administrative secretaries of the arbitral tribunal.30 Delegating tasks of an administrative or clerical nature to administrative secretaries can be a way to improve the efficiency and expeditiousness of the proceedings, especially in complex cases. Administrative secretaries were appointed in 11% of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes.

The importance of expertise

As mentioned earlier in this report, many of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes examined were technical in nature. Such disputes undoubtedly require expertise to be adjudicated in an efficient manner. Ensuring that such knowledge is available throughout the proceedings is one of the SCC’s priorities in contributing to the green transition by providing adequate dispute resolution services.

Making such expertise available starts with the appointment of the arbitral tribunal. Party autonomy is a one of the SCC’s cornerstone principles, so the parties have a great deal of influence over the appointment of the arbitral tribunal and the proceedings in general. The Arbitration Rules set out a default procedure for the appointment of arbitrators, which only applies if the parties have not agreed on another procedure. Where an arbitral tribunal is to consist of more than one arbitrator, each party appoints an equal number of arbitrators while the SCC appoints the chairperson.31 Where an arbitral tribunal is to consist of a sole arbitrator, the parties are given 10 days to jointly appoint the arbitrator, failing which the SCC makes the appointment.32 The same applies in cases using the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, which are always decided by one arbitrator.33 Under the Mediation Rules, the SCC solicits the views of the parties before appointing the mediator and will appoint any mediator jointly proposed by the parties.34 Meanwhile, under the SCC Express Rules, the SCC takes any proposals made by the parties into consideration when appointing the neutral.35

When appointing arbitrators, the SCC carefully considers candidates’ qualifications and specialisations. The SCC seeks to appoint arbitrators who have a good understanding of the subject matter of the dispute.36 As mentioned in the 2019 Report, the SCC does not have a list or roster of arbitrators to choose from. Instead, it is free to appoint the arbitrator best suited to the dispute. This is beneficial in the fast-changing field of climate related arbitration as arbitrators with the necessary technical, regulatory, or sectorial knowledge can be appointed without limitations. As mentioned earlier in this report, many of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes examined concerned renewable energy and construction. In such cases, the SCC generally appointed arbitrators with experience from the renewable energy sector and/or with construction expertise. In the non-technical disputes of a more general commercial nature, arbitrators with expertise in the specific legal area relevant to the dispute were appointed. A minority of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes required specific knowledge within environmental law or climate issues. In such cases, the SCC appointed a chairperson who possessed adequate knowledge of the subject matter while complementing the expertise and qualifications of the arbitrators appointed by the parties. Should specific technical or environmental knowledge be needed, there is no requirement under the Swedish Arbitration Act, i.e., for arbitrations seated in Sweden, regarding the legal qualifications or training of arbitrators. However, it is unusual for arbitrators without legal training to be appointed in SCC cases. Since the SCC will usually appoint the chairperson of the arbitral tribunal or the sole arbitrator, who will have the main responsibility of conducting the proceedings, it rarely appoints arbitrators without legal expertise.

Once the arbitral tribunal has been appointed, the arbitral tribunal is given a wide mandate to conduct the proceedings as it considers appropriate provided that the arbitration is conducted in an impartial, efficient and expeditious manner while providing the parties with an equal and reasonable opportunity to present its case.37 The arbitral tribunal shall hold a case management conference to establish the procedure and conduct of the arbitration.38 The initial case management conference provides the arbitral tribunal and the parties with an opportunity to agree on procedures and rules of conduct tailored to the specific needs of Green Technology Commercial Disputes. Such decisions may concern inter alia written submissions, the format and length of the hearing, document production and the use of expert evidence. In fact, it is mandatory under the SCC Rules for the arbitral tribunal and the parties to seek to adopt procedures enhancing the efficiency and expeditiousness of the proceedings during the case management conference.39

Settlement rate

Article 45 of the SCC Rules concerns settlements or other grounds for terminating the arbitration. Under this provision, the arbitral tribunal may, at the request of the parties, make a consent award recording the settlement of the parties. If the arbitration is terminated for any other reason before the final award is made, the arbitral tribunal shall issue an award recording the termination. The most common situation where arbitral tribunals render termination awards is when the parties withdraw their claims following a settlement.

As mentioned above, final arbitral awards have been rendered in 31 of the Green Technology Commercial Disputes examined. Of these awards, ten were either consent awards or termination awards rendered due to a withdrawal of claims following a settlement, resulting in a settlement rate of 32% in the Green Technology Commercial Disputes.

Introduction: SCC Green Investment Disputes

As mentioned above, the SCC is one of the preferred international forums for the resolution of investment treaty disputes. The SCC has administered the second highest number of investment treaty arbitrations after the dispute resolution organ of the World Bank: the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (“ICSID”).40 Considering the SCC’s strong presence in the field of investment treaty arbitration and the nature of these disputes, specific provisions applicable to investment treaty disputes were introduced to the 2017 version of the Arbitration Rules. The provisions are found in Appendix III to the Arbitration Rules and address inter alia the number of arbitrators and the filing of written submissions by third persons and non-disputing parties.

To adhere to a consistent methodology that can be used to compare the development of the relevant investment treaty disputes, this section adheres to a structure similar to the 2019 Report. Following a general background, this section first identifies investment treaty cases, registered with the SCC since 2019, regarding investments in the green technology sector of the respondent state. Second, this section briefly analyses four publicly available final awards rendered in such cases since 2019.

Investment treaty arbitrations arise from either BITs or multilateral treaties, such as the ECT. As opposed to commercial contracts, BITs and multilateral treaties are entered into by state parties. The general purpose of BITs, usually expressed in the preamble to a BIT, is to strengthen economic co-operation of the contracting states and to stimulate such co-operation by protecting investments made by investors of one state in the territory of the other state.41 The same is true for multilateral investment treaties, such as the ECT. The ECT entered into force in 1998 and currently has 53 contracting parties. Article 2 of the ECT explains its purpose to “establish a legal framework in order to promote long-term co-operation in the field, based on complementarities and mutual benefits, in accordance with the objectives and principles of the Charter”.

The ECT grants a number of substantive rights to investors. They include fair and equitable treatment (“FET”), constant protection and security, most-favoured nation treatment, national treatment and protection against expropriation. Under Article 26 of the ECT, investors can choose to submit disputes to the SCC, ICSID, ad hoc arbitration, the courts or administrative tribunals of the host state, or in accordance with any applicable previously agreed dispute settlement procedure. Arbitration has proven to be preferred for the resolution of ECT disputes and as of 31 December 2021, the SCC has administered 32 cases arising out of the ECT.

Methodology and findings

All investment treaty arbitration cases registered with the SCC between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022 were reviewed to identify cases where the investor had invested in the green technology sector in the respondent state’s territory. For the sake of consistency, this report uses the same definition of the term green technology as in the 2019 Report, i.e. “any process, product or service that reduces negative environmental impacts in support of the Paris Agreement on Climate Change”.

Applying this methodology, the 2019 Report found that 16 investment cases concerning green investments had been registered with the SCC between 2012 and 2018. All cases arose out of the ECT.

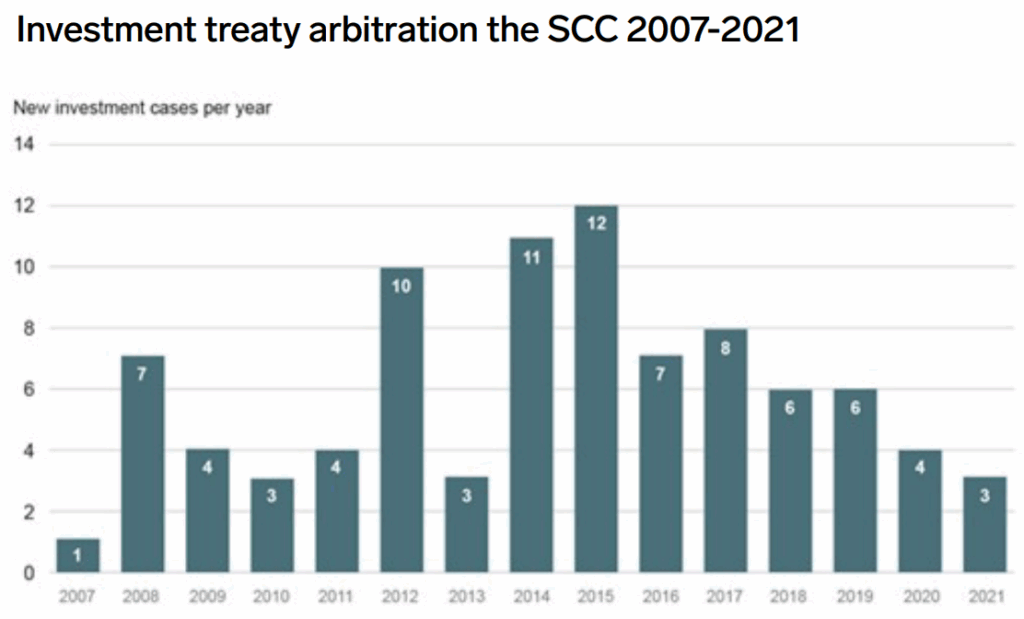

Two green investment treaty arbitrations were registered with the SCC between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022 (“Green Investment Disputes”). Contrary to the increase of Green Technology Commercial Disputes, the number of green investment treaty arbitrations registered with the SCC was significantly lower than in the 2019 Report. A few non-conclusive factors could have contributed to fewer cases being registered.

First, the registration of fewer investment treaty cases in the time period relevant to this report is to be expected considering that the overall time frame is shorter than the one examined in the 2019 Report. The influx of investment treaty cases also tends to fluctuate over time and it peaked during the time period examined by the 2019 Report, as shown in the figure below.

Second, intra-EU investment treaty arbitration has been called into question over the last few years. Considering that these developments have been the subject of extensive research, falling outside the immediate scope of this report, only a brief summary is provided for the sake of context.

In Achmea, the Court of Justice of the European Union (the “CJEU”) declared that arbitration clauses in international agreements between EU Member States, such as the arbitration clause present in a BIT between the Netherlands and Czechoslovakia which was subject to the preliminary questions referred to the CJEU, was precluded by provisions of EU law.42 Following Achmea, many arbitral tribunals found Achmea to not be an obstacle to intra-EU investment treaty arbitration and continued to uphold jurisdiction in a number of such cases, including some of the cases mentioned later in this report.43 As a result of the CJEU’s ruling in Achmea, EU Member States declared that they would terminate intra-EU BITs existing between them. In its subsequent judgment Komstroy, the CJEU extended its findings in Achmea to intra-EU disputes brought under the ECT, interpreting Article 26(2)(c) of the ECT, according to which investors may refer disputes to arbitration, to not be applicable to investment disputes between EU-investors and EU Member States.44

In a political context, formal discussions to modernise the ECT have been ongoing since 2017 with several rounds of negotiation taking place. On 24 June 2022, the signatories to the ECT reached an agreement in principle which concluded the negotiations. Among other things, the agreement in principle resulted in a proposal for the inclusion of provisions concerning sustainable development. The draft text was shared with the contracting parties on 22 August 2022 for adoption by the Energy Charter Conference on 22 November 2022. A number of contracting parties to the ECT, including Poland, Spain, the Netherlands, France, Belgium, and Germany have recently announced their intentions to withdraw from the ECT. Italy withdrew from the ECT in 2016, becoming the first country to do so. However, unilateral withdrawal from states does not immediately put an end to the protection the ECT grants investors. Article 47 of the ECT, commonly referred to as the sunset clause, continues to protect existing investments for 20 years after a host state’s withdrawal.

The impact of these factors, if any, on the number of Green Investment Disputes registered in the time period examined by this report cannot be determined at this time. At the same time, however, they cannot be ignored.

The Green Investment Disputes

Cases registered between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022

Two Green Investment Disputes were registered with the SCC between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022. One case was brought under the ECT and is administered under the Arbitration Rules. In the second case, the SCC acted as appointing authority under the UNCITRAL Rules.

Final awards rendered between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022

Four publicly available final awards were rendered between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022 in investment treaty cases administered by the SCC concerning investments in renewable energy.45 While the awards are publicly available, they were not published by the SCC. No information that is not already publicly available is referred to or analysed in this report. Final awards were rendered in the following cases.

All of these cases were brought under the ECT. Only one of the cases, Green Power, was concluded after the CJEU’s judgment in Komstroy. Like one of the cases examined in the 2019 Report,46 CEF Energia and SunReserve concerned claims brought by investors in solar photovoltaics against Italy in response to Italy’s reforms of incentive schemes it established to encourage investments in renewable energy.47

In CEF Energia, the claimant owned three companies which operated solar photovoltaic plants in Italy. The claimant sought compensation due to regulatory changes which the claimant alleged violated the ECT. The respondent objected to the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal. Further, the respondent argued that its measures did not entitle the claimant to compensation and that the claimant’s investments remained profitable. The arbitral tribunal dismissed the jurisdictional objection, which was in part based on Achmea. In doing so, the arbitral tribunal held that Achmea did not have an application as such to the ECT and lacked a direct impact as undermining the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal. In reaching that conclusion, the arbitral tribunal found that the application of Achmea was limited to the arbitration clause in the BIT that was the subject of the preliminary question referred to the CJEU in Achmea.48

In SunReserve, the three claimants contented that they had invested approximately EUR 100 million to acquire and develop a total of nine solar photovoltaic plants.49 The claimants alleged that the respondent had breached the ECT by backing out of promises made of fixed incentive tariffs and consistent minimum guaranteed prices. The alleged breaches included the failure to grant the investments fair and equitable treatment and the investments being impaired by unreasonable or discriminatory measures.50 The respondent objected to the arbitral tribunal’s jurisdiction, claiming inter alia that the ECT does not cover intra-EU disputes. The respondent also disputed the claimants’ claims on the merits, both in terms of alleged breaches and quantum.51 The arbitral tribunal found that it had jurisdiction over the dispute reasoning that, absent clear indication that the CJEU’s interpretation made in Achmea extended to the ECT, the case fell within the outer limits of the arbitral tribunal’s jurisdiction.52

Like most of the awards examined in the 2019 Report, both FREIF Eurowind and Green Power concerned changes by Spain to regulations adopted to incentivise investment in its renewable energy sector.53 In FREIF Eurowind, the claimant had purchased a 50% preferred equity interest in a portfolio of six wind parks in Spain. According to the claimant, Spain had breached the ECT by reneging on guarantees and commitments implemented to incentivise investments in its renewable energy sector. Spain contended that it had not breached the ECT and objected to the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal.54 The arbitral tribunal found that it had jurisdiction in the case and rejected Spain’s intra-EU jurisdictional objection. The arbitral tribunal held inter alia that neither Article 26 of the ECT nor any claims made by the parties in the arbitration required interpretation and/or application of EU law. The arbitral tribunal also found the ECT to be markedly different from the BIT considered in Achmea.55

In Green Power, the dispute concerned investments made in the Spanish solar energy market which, the claimant argued, were affected by measures adopted by Spain which altered the applicable regulatory framework.56 The respondent objected to the arbitral tribunal’s jurisdiction and disputed the claimant’s claims on the merits.57 The arbitral tribunal upheld the respondent’s jurisdictional objection, reaching the opposite conclusion on jurisdiction as the arbitral tribunals in the cases mentioned above. The arbitral tribunal found that the parties had not agreed on the law applicable to jurisdictional matters.58 The seat of the arbitration was in Sweden and the arbitral tribunal found that pursuant to Section 48 of the Swedish Arbitration Act, Swedish law was applicable to the determination of jurisdictional matters. Further, the arbitral tribunal found that this also attracted the application of EU law, which is part of Swedish law, to determine the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal.59 The arbitral tribunal analysed relevant provisions of the ECT in accordance with the rules for treaty interpretation set out in the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties of 23 May 1969, analysing their ordinary meaning and context as well as the object and purpose of the ECT.60 Following this analysis, as well as an analysis of the wider body of legal relations between the claimant’s state and the respondent state, the arbitral tribunal found that Achmea and Komstroy were relevant to the respondent’s jurisdictional objection and concluded that the arbitral tribunal did not have jurisdiction to hear the claimant’s claims.61

The observation in the 2019 Report that the arbitral awards did not contain substantive arguments related to obligations under international climate agreements or climate policy holds true for the cases examined in this report as well. In the arbitral awards examined in this report, the awards mention certain international agreements as a background to the relevant regulatory frameworks adopted in Italy and Spain. In SunReserve, for example, the award mentions the role that inter alia the Kyoto Protocol had in setting environmental targets in the development of Italy’s energy policy.62 Similarly, the award in FREIF Eurowind mentions that the series of policies Spain adopted were implemented in response to an EU directive requiring EU Members States to reduce their carbon emissions in line with obligations under the Kyoto Protocol.63 Meanwhile, the award in Green Power notes that Spain implemented various measures and incentives to reach EU targets and establish a sustainable energy system.64

Specific procedural features

The 2019 Report observed two procedural features present in all five awards examined in that report. The first was that the cases required specific expertise in renewable energy, taxation and finance. The second was that the arbitral tribunals allowed third party participation through amicus curiae briefs. These features were present in the cases examined in this report as well.

As noted in the 2019 Report, besides the appointed arbitrators possessing the necessary knowledge and qualifications, expert evidence plays an important role in investment treaty cases concerning renewable energy. All of the awards examined in this report contain references to expert evidence presented by the parties. The expertise concerned legal, regulatory, and financial issues as well as issues quantum.

As an example of the use of quantum experts, in CEF Energia the claimant’s expert had submitted calculations of losses allegedly suffered by one of the claimant’s companies due to the respondent’s breaches of the ECT. The respondent’s expert had presented calculations which, according to the arbitral tribunal, did not question the correctness of the claimant’s expert, but instead approached the underlying methodology differently. The arbitral tribunal concluded that it preferred the methodology of the claimant’s expert and proceeded to examine the key assumptions used by the claimant’s expert in his calculations. The arbitral tribunal found that one key assumption in the calculations had to be changed following the arbitral tribunal’s findings on the merits and awarded the claimant an adjusted amount.65

In SunReserve, the parties presented expert evidence from quantum experts as well.66 The arbitral tribunal did not find it necessary to examine the parties’ respective submissions relating to the quantification of claimants’ alleged damages, including quantum expert reports, since it found that the claimants had not established the respondent’s liability under the ECT.67 However, the award still contained references to reports from the quantum experts. For example the arbitral tribunal referred to the report of the claimants’ quantum expert in its considerations of whether reduced incentive tariffs resulted in unfair remuneration for any of the claimants’ power plants. The arbitral tribunal also considered both the reports and testimonies of the parties’ regulatory and quantum experts in determining whether the respondent’s enactment of one of the decrees that led to the dispute had frustrated the claimants’ legitimate expectations of a fair remuneration.68

Similarly, the arbitral tribunal in FREIF Eurowind found that the respondent had not violated the ECT and international law and dismissed the claimant’s claims.69 But references to the reports and testimonies of the parties’ financial experts were still made. The claimant’s primary claim on the merits was that the respondent had frustrated its legitimate expectations, which the arbitral tribunal found to be a component of the FET standard of the ECT.70 Among other things, the arbitral tribunal’s determinations focused on whether the respondent had failed to honour the claimant’s expectation of a reasonable return on its investment.71 The arbitral tribunal found that a specific benchmark reasonable rate of return was understood by the claimant when it invested.72 Considering the expert evidence submitted by the parties, the arbitral tribunal concluded that the calculations of either parties’ experts resulted in an internal return on investment above the benchmark rate, which made it clear to the arbitral tribunal that the respondent hade not frustrated the claimant’s expectation of reasonable return.73 In Green Power, the arbitral tribunal did not hear the claims on the merits since it found that it lacked jurisdiction to do so.

Experts also provided opinions on legal and regulatory issues in the cases in which arbitral awards were rendered.

In SunReserve for example, the parties presented Italian law experts and regulatory experts.74 The claimants argued that the respondent had breached the FET standard under the ECT by violating the claimants’ legitimate expectations. To support their assertion, the claimants relied on a report from their Italian Law expert to show that contracts entered into with an “implementing body” were “individual and actual measures” on which investors’ legitimate expectations of fixed tariffs for 20 years were based.75 Both the claimants’ and the respondent’s legal experts elaborated on the nature of these instruments.76 In assessing the extent to which the instruments had created expectations for the claimants, the arbitral tribunal held that it was not convinced by the criticism of the respondent’s position presented by the claimants or their legal expert.77 In the same case, the claimants’ legal expert elaborated on the hierarchical position of the Italian decrees that led to the claims in dispute in comparison to other sources of law.78 It also relied on its regulatory experts to contend that certain measures the respondent implemented were arbitrary, discriminatory and inefficient.79

In Green Power, the respondent submitted a legal opinion concerning its intra-EU jurisdictional objection.80

As noted in the 2019 Report, third party submissions by amicus curiae have increased in investment treaty arbitration in general. The European Commission made submissions arguing against the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunals in CEF Energia, SunReserve, and Green Power.81 In FREIF Eurowind, the European Commission submitted a request for leave to intervene as a non-disputing party in the arbitration, however, the arbitral tribunal did not allow the Commission’s request for leave.82

Conclusions

The SCC’s mission is to facilitate trade and business by providing a neutral, independent and impartial venue for dispute resolution. To accomplish this, the SCC has positioned itself at the forefront of change to meet the developing needs of the business community. The SCC Arbitration Rules alongside other tools, such as the Mediation Rules and the SCC Express, provide efficient forms of dispute resolution that are well-suited to facilitating the transition to a low-carbon economy.

This report has found that parallel to a global increase in climate change litigation, the number of registered SCC cases where one or more parties used a green technology as part of their main business activity increased significantly between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022 compared to cases registered between 2012 and 2018. This finding indicates that the SCC is an increasingly attractive venue for the resolution of disputes involving companies whose commercial activities reduce the negative effects of climate change. This report’s findings suggest that this is also the case in an international context, since the share of disputes involving parties from countries other than Sweden has increased.

The SCC remains one of the main fora for resolving investment treaty disputes. However, fewer investment treaty disputes concerning investment in renewable energy were registered between 1 January 2019 and 1 October 2022 as compared to the number of cases registered between 2012 and 2018. Possible factors contributing to this include the influx of cases fluctuating over time and recent legal and political developments in the investment treaty arbitration field relating to intra-EU investment treaty arbitrations, including ECT arbitrations. At the time of writing this report, no firm conclusions can be drawn on the possible implications of these developments, if any, for future investment treaty cases regarding investments in renewable energy.

References

2 Article 2.1(a) of the Paris Agreement.

3 UNEP (2022): Adaptation Gap Report 2022: Too Little, Too Slow – Climate adaptation failure puts world at risk (“UNEP Adaption Gap Report 2022”), Glossary, VIII.

4 IPCC 2022: Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [P.R. Shukla, J. Skea, R. Slade, A. Al Khourdajie, R. van Diemen, D. McCol- lum, M. Pathak, S. Some, P. Vyas, R. Fradera, M. Belkacemi, A. Hasija, G. Lisboa, S. Luz, J. Malley, (eds.)] (“IPCC 2022”), p. 10.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid., p. 15.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid., p. 17. A figure illustrating the regulatory increase is that according to one source, almost 3,000 climate change related laws and policies have been adopted globally. See Climate Change Laws of the World database, Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, available at: https://climate-laws.org/.

9 IPCC 2022, pp. 21–43 and the IPCC press release dated 9 August 2021, available at: https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2021/08/IPCC_.

10 UNEP (2022): Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window – Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies (“UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2022”), Executive Summary, XVI.

11 UNEP Adaption Gap Report 2022, Executive Summary, XII.

12 UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2022, p. 65.

13 Article 2.1(c) of the Paris Agreement.

14 IPCC 2022, p. 17.

15 UNCTAD (2022): International Investment in Climate Change Mitigation and Adaption: Trends and Policy Developments, p. 4.

16 Ibid., p. 6.

17 The executive summary of the BloombergNEF report is available here: https://assets.bbhub.io/professional/sites/24/Energy-Transition-Investment-Trends-Exec-Summary-2022.pdf

18 Ibid.

19 UNEP (2020): Global Climate Litigation Report: 2020 Status Review, pp. 4–6.

20 Lucy Greenwood, ‘The Canary Is Dead: Arbitration and Climate Change’, in Maxi Scherer (ed), Journal of International Arbitration, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2021, Volume 38 Issue 3) pp. 309–326.

21 https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/our-services/investment-disputes/.

22 Available here: https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/resource-library/sustainability-commitment/.

23 The Campaign for Greener Arbitrations is an initiative to reduce the environmental impact of international arbitrations. Read more about the initiative here: https://www.greenerarbitrations.com/.

24 Article 49(3) of the Arbitration Rules and the Rules for Expedited arbitration.

25 Article 49(6) and Article 50 of the Arbitration Rules and the Rules for Expedited arbitration.

26 IPCC 2022, p. 52.

27 Article 1 of the IED.

28 Article 9 of the IED.

29 The same provision is found in Article 40 of the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations.

30 Article 24 of the Arbitration Rules and Article 25 of the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations.

31 Article 17(4) of the Arbitration Rules.

32 Article 17(3) of the Arbitration Rules.

33 Article 18(2)–(3) of the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations.

34 Article 6(1)–(2) of the Mediation Rules.

35 Article 6 of the SCC Express Rules.

36 SCC Policy on Appointment of Arbitrators Section II(4).

37 Article 23 of the Arbitration Rules and Article 24 of the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations.

38 Article 28 of the Arbitration Rules and Article 29 of the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations.

39 Article 28(3) of the Arbitration Rules and Article 29(3) of the Rules for Expedited Arbitrations.

40 https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/our-services/investment-disputes/.

41 The Basic Features of Investment Treaties’, in Campbell McLachlan, Laurence Shore, et al., International Investment Arbitration: Substantive Principles (Second Edition), Oxford International Arbitration Series, (© Campbell McLachlan, Laurence Shore, and Matthew Weiniger 2017; Oxford University Press 2017) pp. 28–29.

42 Judgment of 6 March 2018, Achmea, C-284/16, ECLI:EU:C:2018:158, para. 60.

43 See Crina Baltag and Stefan Dudas, ‘Chapter 3: Achmea, Arbitral Tribunals and the ECT: Modernisation or Regression?’, in Ana Stanič and Crina Baltag (eds), The Future of Investment Treaty Arbitration in the EU: Intra-EU BITs, the Energy Charter Treaty, and the Multilateral Investment Court, (© Kluwer Law International; Kluwer Law International 2020) pp. 23-42.

44 Judgment of 2 September 2021, Komstroy, C-741/19, ECLI:EU:C:2021:655, para. 66.

45 The final awards are publicly available at https://www.italaw.com/ and https://jusmundi.com/en/.

46 Greentech Energy Systems A/S, Novenergia II Energy and Environment and Novenergia Italian Portfolio SA v. Italian Republic.

47 CEF Energia, para. 2; SunReserve, para. 278.

48 CEF Energia, paras. 97–98.

49 SunReserve, para. 183.

50 SunReserve, paras. 278–279.

51 SunReserve, paras. 283-286.

52 SunReserve, para. 444.

53 FREIF Eurowind, para. 1; Green Power, para. 5.

54 FREIF Eurowind, paras. 1–5.

55 FREIF Eurowind, paras. 329–330.

56 Green Power, para. 5.

57 Green Power, para. 58.

58 Green Power, para. 158.

59 Green Power, paras. 165–166 and 172.

60 Green Power, paras. 336–412.

61 Green Power, paras. 445–478.

62 SunReserve, paras. 99–102.

63 FREIF Eurowind, para. 156.

64 Green Power, para. 60.

65 CEF Energia, paras. 268–284.

66 SunReserve, para. 60.

67 SunReserve, para. 1013.

68 SunReserve, paras. 841-871.

69 FREIF Eurowind, para. 691.

70 FREIF Eurowind, para. 534.

71 FREIF Eurowind, para. 562.

72 FREIF Eurowind, paras. 566 and 568.

73 FREIF Eurowind, para. 570.

74 SunReserve, para. 60.

75 SunReserve, para. 601.

76 SunReserve, paras. 822-823.

77 SunReserve, para. 829.

78 SunReserve, para. 794.

79 SunReserve, para. 925.

80 See for example Green Power, para. 233.

81 CEF Energia, paras. 13–19 and 59; SunReserve, para. 41 and paras. 336–349; Green Power, paras. 27, 183–184 and 316–318.

82 FREIF Eurowind para. 54.