SCC Practice Note: Emergency arbitrator decisions rendered 2023-2025 and reflections on 15 years

Authors: Jake Lowther and Frederik Hummelmose1

Table of contents

Introduction

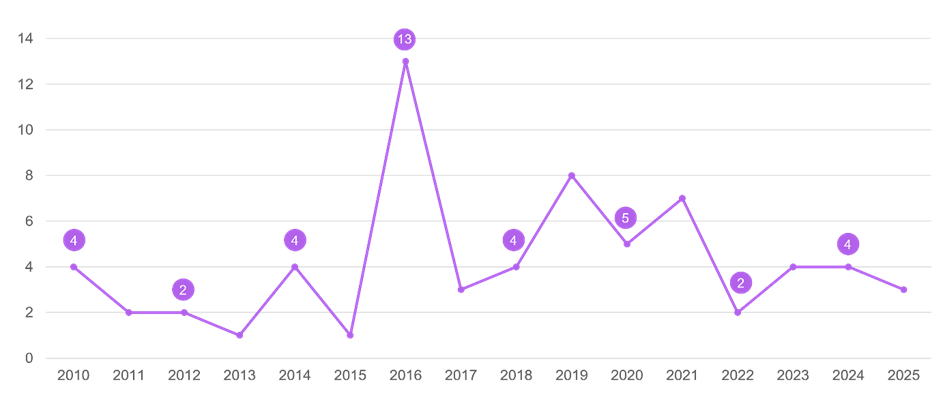

In 2010, the SCC was the first major international arbitration institute to provide for the appointment of an emergency arbitrator when it added Appendix II to the SCC Arbitration Rules and SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitration (the SCC Rules). Thus, 2025 represents 15 years of emergency arbitration at the SCC. This milestone provides the opportunity to reflect on how the emergency arbitrator mechanism has developed and to consider the future ahead. As of 31 December 2025, the SCC had received a total of 67 applications for the appointment of emergency arbitrators. The parties involved cover a broad range of nationality, geography, industry and sector, and include public and private entities, as well as states.

Building on from the SCC’s previous practice notes over the years,2 this practice note provides a short overview of the procedure, before summarising the emergency arbitrator decisions rendered in SCC cases during the period 2023–2025. It focuses on commercial arbitration and will only make a short remark on investment arbitration.

The procedure

Under Appendix II of the SCC Rules, a party may apply for the appointment of an emergency arbitrator before the dispute has been referred to the Arbitral Tribunal.3

Upon receiving an application for the appointment of an emergency arbitrator, the SCC will immediately notify the counterparty and seek to appoint an emergency arbitrator within 24 hours.4 To facilitate this, the SCC has a dedicated email address for emergency arbitrator applications that is monitored during evenings and weekends, all year round.5

Once an emergency arbitrator has been appointed, the SCC promptly refers the application to the emergency arbitrator for a decision. A decision on interim measures must be made no later than five days after the referral of the case. The SCC may extend this time limit upon a reasoned request from the emergency arbitrator, or if otherwise deemed necessary.6

An emergency decision is binding on the parties but ceases to be so in the event of the following:

- if decided by the emergency arbitrator or an arbitral tribunal,

- if an arbitral tribunal makes a final award,

- if arbitration is not commenced within 30 days of the emergency decision, or

- if the case is not referred to an arbitral tribunal within 90 days of the emergency decision.7

The emergency arbitrator holds the same powers as those of the Arbitral Tribunal to grant interim relief and may grant “any interim relief it deems appropriate”.8 In addition, the emergency arbitrator enjoys broad authority to conduct the emergency proceedings in such a manner it considers appropriate.

According to the SCC’s jurisprudence, certain standards for exercising the emergency arbitrator’s broad powers, and the granting of interim relief, have been established over the years. These typically require the applicant to demonstrate:

- A reasonable possibility of success on the merits – the claimant must demonstrate at least a prima facie case.

- Irreparable harm – the claimant must show that it will incur irreparable harm without an interim decision.

- Urgency – the claimant must demonstrate that the matter at hand is so urgent that it cannot wait for an arbitral tribunal’s final award.

- Proportionality – the claimant’s requested relief must be proportional to the consequences to be averted.

According to the practice at the SCC,9 the majority of emergency arbitrators have applied these standards, with some variations, alongside guidance from the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration.

– Sara Catoni, General Counsel and Director of the Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions (SKR)It is a reliable process where both sides are heard, and the case is well analysed. It is impressive that the whole process including the decision takes only five days.

Emergency arbitrator decisions (2023-2025)

Request for interim relief granted

Case 1

Background

The respondent, a Russian entity, had previously been a member of the claimant’s corporate group, the claimant being a Danish company. During this period, the respondent held, pursuant to license agreements, exclusive rights to use ten of the claimant’s trademarks in Russia and several other jurisdictions. Following steps taken by the claimant to divest its shares in the respondent, the Russian state placed the respondent under “temporary management”. Consequently, the claimant sought to terminate the license agreements following which the respondent continued to use and profit from the trademarks in question.

Request for interim measures

The claimant requested an emergency decision ordering the respondent to immediately cease and desist the use of the ten trademarks and related know-how to import, produce, pack, distribute, sell, advertise, promote and export products in Russia and several Eurasian countries.

Procedure

The SCC appointed the emergency arbitrator the same day it received the application.

The following day, the case was referred to the arbitrator, and an online case management conference was held. The respondent was absent from the conference, however, shortly before the meeting, an employee of the respondent had sent an email to the emergency arbitrator objecting to the jurisdiction of the SCC.

A second online case management conference was held the following day, from which the respondent was again absent.

The emergency decision was rendered four days after the referral. The respondent’s sole participation in the proceedings consisted of the aforementioned email.

The seat of the emergency arbitration was Stockholm, Sweden.

Analysis and decision

Given the respondent’s absence from the proceedings, the emergency arbitrator first addressed whether the respondent had been given the opportunity to be heard before proceeding to the jurisdictional objection of the respondent and the substantive issues.

First, the arbitrator noted that the respondent’s omission to file any reply or submission (apart from the e-mail) did not prevent the proceedings from continuing (Art. 9(3) and 35(2) SCC Rules). Further, it was found that the respondent had been aware of the proceedings and had been given sufficient opportunity to present its case. This was based on the fact that the alleged legal director of the respondent had called in to the first online case management conference, where he briefly stated that he was not authorised to act on behalf of the respondent (the arbitrator found this comment surprising given his alleged role), and that the arbitrator had corresponded by e-mail with an employee of the respondent (including the jurisdictional objection).

Second, the emergency arbitrator found that the SCC had jurisdiction even though the respondent had initiated court proceedings in Russia because the claimant had objected to the Russian court’s jurisdiction, had not made any submissions on the merits, and therefore had not waived the arbitration agreements in the license agreements.

Finally, the emergency arbitrator noted that it had the authority to grant any interim measure it deemed appropriate (Art. 37 SCC rules and 1(2) Appendix II), provided that the following conditions were met: a prima facie case, irreparable harm, urgency, and proportionality.

A prima facie case: The arbitrator initially found that the license agreements contained provisions that they would automatically expire if either party ceased to be part of the claimant’s group. Hereafter the arbitrator turned to an assessment of whether the respondent had in fact ceased to be part of the claimant’s group due to the “temporary management” of the Russian state. It was found that “control” was the determining factor as to whether a takeover had taken place. The emergency arbitrator found it “more likely than not” that an arbitral tribunal would conclude that under the governing law of the contract, the claimant had lost control of the respondent.

Irreparable harm: The emergency arbitrator noted that it has been argued that “serious or substantial harm” would be sufficient for granting interim measures because a literal interpretation of irreparable harm would limit interim measures to cases where a party would become effectively insolvent, or where enforcement of the final award would be impossible. The claimant submitted in its application that continued association with Russia would pose a serious risk for reputational damages due to “Russia’s… war against Ukraine”. The emergency arbitrator noted that goodwill and reputation is of utmost importance to the value of a trademark, and goodwill value can be lost very quickly. Consequently, the emergency arbitrator concluded that the reputational damage to a trademark may be irreparable in the sense that the harm would not be adequately reparable by an award of damages in the subsequent main arbitration.

Urgency: The arbitrator found that the court proceedings initiated by the respondent indicated that it intended to continue using the trademarks, and that the core function of an intellectual property right is the right to prohibit others from using it. On this background the emergency arbitrator concluded that the requirement of urgency to be fulfilled.

Proportionality: Lastly, the arbitrator found a cease-and-desist order to be proportional because it would only prevent the respondent from using the ten trademarks of the license agreements. Since the respondent produced similar products under different brands, the interim measure would not cause a full stop of the respondent’s ability to produce and sell these products.

Against that background, the emergency arbitrator granted the interim measures requested.

Case 2

Background

The Polish claimants and the Swedish respondent entered into an EPC contract under which the claimants were joint contractors and the respondent the buyer.

Following alleged problems with delays and health, safety, and environmental matters in connection with the project, the respondent withheld milestone payments. The respondent submitted that it had validly set off the overdue milestone payments against health, safety, and environmental expenses for which the claimants should have reimbursed the respondent.

Additionally, the respondent asserted a claim for “delay liquidated damages”. The claimants did not contest this claim but submitted that their claim for overdue milestone payments exceeded the respondent’s claim for liquidated damages and that they had validly set off the delay liquidated damages against the overdue milestone payments.

Accordingly, the parties disputed the validity of each other’s set-off claims. The respondent called upon a parent guarantee and threatened to call upon a performance security under the EPC contract if the parent guarantee was not paid.

Request for interim measures

The claimants sought an emergency order restraining the respondent from making any payment demands under the performance security until the validity of the respondent’s demands had been finally determined.

Procedure

The SCC appointed the emergency arbitrator and referred the case to the emergency arbitrator the day after receiving the application.

The following day, the respondent submitted its answer to the claimants’ application.

Three days after the referral, the claimants submitted a reply to the respondent’s answer, and a video hearing was held. Following the hearing, the claimants amended the wording of their request for relief.

Four days after the referral, the parties submitted their costs submissions.

The emergency award was rendered five days after the referral.

The seat of the emergency arbitration was Stockholm, Sweden.

Analysis and decision

The emergency arbitrator first noted that neither party had raised any jurisdictional objections and accordingly concluded that it had jurisdiction pursuant to the arbitration clause agreed between the parties.

The emergency arbitrator then noted that it had broad discretion to grant any interim measure it deemed appropriate and that, in determining the applicable test, it was relevant to consult Articles 17 and 17A of the UNCITRAL Model Law.

Regarding the applicable test, the emergency arbitrator found that the wording of Article 17(2)(a) of the UNCITRAL Model Law – “[m]aintain or restore the status quo pending determination of the dispute” – was aimed at ensuring that issues central to the dispute could be determined in the proper manner. The emergency arbitrator stated that it was satisfied that the claimants sought to maintain the status quo, as to whether the performance security could be called upon was the central issue in dispute.

The emergency arbitrator then addressed the balance of harm, first finding that the claimants had presented prima facie evidence of considerable harm and that at least part of this harm might not be adequately reparable by an award of damages, including adverse impacts on the claimants’ credit rating, reputation, and credibility. Second, the emergency arbitrator recognised that preventing the respondent from calling upon the performance security could potentially result in substantial harm to the respondent. However, the emergency arbitrator also held that the effect of any emergency decision would be temporary, that a subsequent arbitral tribunal could revisit the issue of interim measures, and that the respondent had not expressed an urgent need to call upon the performance security. As such, the emergency arbitrator concluded that the potential harm for the claimants outweighed the potential harm for the respondent.

On the issue of a reasonable possibility of success on the merits, the emergency arbitrator first stated that it was important not to prejudge the merits of the case at an interim stage and stressed that the following determinations were made on a prima facie basis only. The emergency arbitrator then found that the claimants had established a prima facie case both that they had a right to exercise a set-off against the delay liquidated damages and that they had validly exercised that right. At the same time, the emergency arbitrator was not satisfied that the respondent had validly exercised its right to set off the overdue milestone payments against the health, safety, and environmental expenses.

Finally, on the issue of urgency, the emergency arbitrator concluded that this criterion was satisfied because the respondent had made an unambiguous threat to call upon the performance security and the respondent had not provided any undertaking during the emergency proceedings that it would refrain from doing so.

On the above background, the emergency arbitrator granted the claimants’ request for interim relief.

Request for interim relief granted in part

Case 3

Background

The Swedish claimant entered into separate lending agreements with several individuals of Thai nationality, the respondents. The agreements contained lengthy arbitration clauses setting out detailed procedures and rules for any arbitration.

Under the lending agreements, the claimant was to pay the loans in two tranches to each of the respondents, and the respondents each put up shares as collateral. After paying the first tranche, the claimant “paused” the second tranche for reasons related to Thailand and disposed of a portion of the collateral shares.

The respondents considered this disposal to be unlawful and obtained a temporary injunction from the Thai courts. The claimant considered the initiation of court proceedings to be contrary to the arbitration clause and to constitute an event of default and accordingly commenced a joint arbitration against the respondents before the SCC.

The SCC determined that it did not manifestly lack jurisdiction and that the parties should share the advance on costs equally. The arbitration clauses stated, inter alia, that “[a]ll of the Parties [sic] arbitration […] costs will be borne by the [respondent] at onset of proceedings irrespective of the outcome of the arbitration”. The respondents refused to pay their share of the advance on costs, arguing that the arbitration clauses were null and void or should be set aside under the applicable substantive law, inter alia, on the ground that the respondents were consumers.

Request for interim measures

The claimant requested an emergency order that (i) the respondents fully comply with the arbitration clauses in the agreements and bear the costs of the main arbitration, (ii) the respondents remit their portion of the advance on costs, and (iii) the claimant be allowed to sell the pledged collateral to cover the cost of the main arbitration.

Procedure

The SCC appointed the emergency arbitrator and referred the case the day after receiving the application. On the same day, the emergency arbitrator issued Procedural Order 1.

Two days after the referral, the respondents submitted their defence.

Three days after the referral, the claimant submitted its rejoinder.

Four days after the referral, the respondent submitted its sur-rejoinder.

The award was rendered five days after the referral.

The seat of the emergency arbitration was Stockholm, Sweden.

Analysis and decision

First, the emergency arbitrator confirmed that it had jurisdiction.

Next, the emergency arbitrator found that the respondents had not sufficiently evidenced that they were consumers and, consequently, that the arbitration agreements were not invalid on this ground.

The emergency arbitrator then found that only an agreement to arbitrate could be discerned from the detailed arbitration clauses. As such the emergency arbitrator found that the numerous additional provisions in the arbitration agreements could potentially render them invalid, as they risked constraining an arbitral tribunal whose prerogative it was to determine the outcome of the dispute and the conduct of the proceedings in cases where the parties disagreed on procedural matters or the validity of the arbitration agreement.

On this basis, the emergency arbitrator ordered the respondents to pay their share of the advance on costs.

The emergency arbitrator then addressed the claimant’s two remaining requests: that the respondents bear the full costs of the main arbitration in accordance with the arbitration agreements, and that the claimant had a right to sell the collateral shares. The emergency arbitrator found that there were reasonable grounds to vary the arbitration agreements, suggesting that the claimant had not established a prima facie case on these issues.

In addition, the emergency arbitrator found that the claimant would not suffer irreparable harm by not having the costs awarded at the onset of the main arbitration. Nor was the relief urgent or proportional. Lastly, the emergency arbitrator noted that if the arbitral tribunal in the main arbitration decided in favour of the claimant on these issues, the claimant could recover the costs at such time, while the respondent would be more likely to suffer irreparable harm if further shares were sold.

On this basis, the emergency arbitrator denied the claimant’s requests (i) and (iii). Accordingly, the emergency arbitrator granted request (ii), ordering the respondents to remit their share of the advance on costs, while denying requests (i) and (iii).

A subsequent request by the claimant to revoke or amend the emergency award due to the emergency arbitrator exceeding its jurisdiction was denied by the emergency arbitrator.

Case 4

Background

In connection with the acquisition of a company (the Company) through its subsidiary (the Subsidiary), the claimant, a Swedish entity, reorganised its corporate structure and entered into a shareholders’ agreement (the SHA) regarding the Subsidiary with the seller of the Company. The SHA contained non-competition, non-solicitation, and confidentiality clauses.

Subsequently, the Company acquired a competing company (the Competitor) from the respondents, a Swedish entity and an individual, through a share purchase agreement (the SPA), which also contained non-competition, non-solicitation, and confidentiality clauses. Additionally, the SPA obligated the respondent entity to reinvest part of the sale profit in the Subsidiary. As a result of this reinvestment, the respondent entity became a party to the SHA.

In addition, the respondent individual, who founded the respondent entity, entered into an employment agreement with the Competitor, which likewise contained non-competition, non-solicitation, and confidentiality clauses.

Request for interim measures

The claimant requested an emergency decision ordering the respondents to immediately cease and desist from engaging, directly or indirectly, in any competitive activities, and to preserve and refrain from deleting, modifying, concealing, or transferring any evidence relevant to the dispute.

Procedure

The SCC appointed the emergency arbitrator and notified the respondents on the same day it received the application.

The following day, the case was referred to the emergency arbitrator, and a case management conference was held. The emergency arbitrator applied, with the consent of the parties, for a one-day extension of the deadline for rendering the emergency award.

The request was granted the following day.

Three days after the referral, the respondent submitted its response to the claimant’s application. The same day, the claimant submitted a rejoinder regarding new circumstances.

Four days after the referral, the respondent submitted a sur-rejoinder on the new circumstances. The same day, both parties submitted cost submissions.

The emergency award was rendered six days after the referral.

The emergency arbitration was Stockholm, Sweden.

Analysis and decision

First, the emergency arbitrator noted that it had jurisdiction pursuant to the SHA, noting that neither party had raised any objection.

The arbitrator then stated that pursuant to the SCC Rules, for interim measures to be granted, the claimant must (i) have a reasonable possibility of success on the merits of the case (a prima facie case), (ii) demonstrate that without such interim measure it will incur irreparable harm, (iii) demonstrate that the matter is so urgent that it cannot wait for a final award, and (iv) demonstrate that the requested relief is proportional to the consequences to be averted. The arbitrator also noted that the assessment did not comprise a full and complete examination of the merits of the case.

On the prima facie case requirement, the emergency arbitrator found it “likely” that the respondents had breached, both directly and indirectly, the non-competition, non-solicitation, and confidentiality clauses, and that such breaches would constitute material breaches of the SHA. Consequently, the claimant had established a reasonable possibility of success on the merits. The emergency arbitrator further noted that a full and complete examination of the competing business allegations could not, nor should, be undertaken in emergency arbitration proceedings, as the conditions for such an examination are not afforded to the emergency arbitrator.

Regarding the criterion of irreparable harm, the emergency arbitrator found that the Company was probably suffering imminent economic loss, and that consequently the claimant would probably suffer an indirect loss. Further, it was held that establishing, assessing, and proving all damages may be very difficult, if not practically impossible, in a later arbitral proceeding. Consequently, the claimant’s harm would be irreparable and could not be adequately compensated by damages at a later stage, and the prerequisite for irreparable harm was fulfilled.

As to the urgency, the emergency arbitrator found that, absent interim measures, there was an imminent risk that the respondents would take actions that could permanently harm the claimant, including by increasing their capacity to manufacture and sell competing products. The emergency arbitrator held that immediate protective measures were necessary and noted that the time that had elapsed before the claimant filed its application for an emergency arbitrator, as argued by the respondents, did not affect whether the urgency requirement was satisfied.

Regarding proportionality, the emergency arbitrator found that the claimant faced a risk of irreparable harm. At the same time, the competing companies could still conduct business without the involvement of the respondents, and if they intended to engage in competitive activities, they could seek the claimant’s approval in accordance with the SHA. The emergency arbitrator also noted that the measures requested by the claimant were aimed at preserving the status quo of the SHA, and that it could not be considered disproportionate to require the respondents to comply with the terms of the SHA to which they were bound. Consequently, the emergency arbitrator found that the claimant’s interest in obtaining the interim measures outweighed the potential adverse consequences to the respondents.

Against the above background, the emergency arbitrator granted the claimant’s request to order the respondent to immediately cease and desist from engaging, directly or indirectly, in any competitive activities.

Regarding the claimant’s request for an order requiring the respondents to preserve and refrain from deleting, modifying, concealing, or transferring any evidence relevant to the dispute, the emergency arbitrator found that the request contained no further specification as to what items it referred to or what they contained. The arbitrator held that such a request was too vague and unspecific to be enforceable. Furthermore, the requested interim measure was not deemed appropriate, and the arbitrator noted that other procedural mechanisms were available to the claimant, both before national courts and in arbitration proceedings. Consequently, this request was denied.

Request for interim relief denied

Case 5

Background

The claimant, a Russian subsidiary of a German company, and the respondent, a Russian company, entered into an EPC contract providing that either party would be released from its obligations if performance of the contract would result in sanctions being imposed on that party, its affiliates, or its major subcontractors.

Following amendments to EU sanctions against Russia, the claimant notified the respondent that the EPC contract fell within the scope of the new sanctions and ultimately suspended all work.

The respondent claimed that the suspension of work was unlawful, as the sanctions did not preclude the claimant from performing its obligations, and demanded that the claimant return all unearned advance payments. As the claimant did not return the advance payments, the respondent filed for interim relief against the claimant with Russian state courts. The application was dismissed.

Prior to the amendments to the sanctions, Russia had adopted legislation establishing the exclusive jurisdiction of Russian state courts over disputes involving Russian individuals or entities subject to sanctions, unless a treaty or agreement between the parties provided otherwise.

The claimant averred that Russian courts had wrongly applied this principle in cases where the dispute was merely related to sanctions – not individuals or entities subject to sanctions. Further, the claimant asserted that Russian entities had increasingly disregarded arbitration agreements by bringing claims against foreign contractual counterparties before Russian state courts, which had rejected claims and arguments solely on the basis that the foreign party was domiciled in an unfriendly jurisdiction or had relied on sanctions.

Request for interim measures

The claimant requested an emergency decision ordering the respondent to refrain from initiating or continuing any litigation before Russian state courts and from enforcing any decisions that may be obtained in such proceedings.

Procedure

The SCC appointed the emergency arbitrator and referred the case the day after receiving the application. The arbitrator issued Procedural Order 1 on the same day.

The claimant then made an additional written submission. The respondent failed to provide any timely submission.

The emergency decision was rendered five days after the case was referred to the emergency arbitrator.

The seat of the emergency arbitration was Stockholm, Sweden.

Analysis and decision

The emergency arbitrator began by noting that the EPC contract referred to arbitration administered by the SCC. He further observed that he “need not delve into the merits of the dispute, but rather must only review the submitted documentation to determine whether the Claimant’s case is prima facie covered by the Contract”. Having determined that the case was prima facie covered by the Contract, the emergency arbitrator concluded that it had jurisdiction.

The emergency arbitrator then noted that under the SCC Rules it had broad discretion to grant interim measures.

Notably, the emergency arbitrator considered urgency and a prima facie case on the merits to reflect the international norms with respect to the granting of interim measures while noting that other factors may also be relevant to the analysis. The emergency arbitrator also addressed irreparability of harm in its assessment but did not expressly consider the proportionality of the relief sought.

The emergency arbitrator then noted that the analysis of the relief sought could not be conducted in the same manner as by a duly constituted arbitral tribunal, given that an arbitral tribunal would have the ability to modify its decision on interim relief, whereas an emergency arbitrator becomes functus officio upon issuing the decision. Accordingly, the emergency arbitrator considered the threshold for granting interim relief to be considerably higher.

Without elaboration, the emergency arbitrator concluded that the relief sought was premature and therefore not urgent.

Furthermore, the emergency arbitrator observed that an arbitral tribunal constituted to adjudicate on the merits of the case would be in a better position to determine whether the respondent had a right to pursue its claims before domestic courts and to grant any relief it deemed appropriate, thereby declining to conduct a prima facie assessment of the merits.

Moreover, the emergency arbitrator stated that, at the appropriate time, an arbitral tribunal would be in a position to uphold the claimant’s rights. Accordingly, the criterion of irreparable harm was not satisfied.

On that background, the emergency arbitrator denied all the claimant’s requests for interim relief.

Case 6

Background

The claimant, a Curaçaoan company, and the respondent, a Hong Kong holding company, entered into a share purchase agreement (SPA) under which the claimant was to acquire the respondent’s shares in one of the respondent’s companies (the Company). Payment was to be made in two tranches.

The respondent undertook several obligations for completion of the transaction. The SPA provided that if these obligations were not satisfied within 15 business days after commencement of the completion phase, each party had the right to terminate the agreement, in which case the respondent would be obliged to refund the first tranche.

After paying the first tranche, the claimant requested that the respondent provide certain documents, which was one of the obligations undertaken by the respondent. According to the claimant, the respondent failed to provide the documents within the agreed 15-day period, refused to discharge a newly revealed debt of the Company, and refused to refund the first tranche. The claimant consequently issued a termination notice and demanded a refund of the first tranche.

According to the respondent, the completion phase had not yet commenced. The respondent asserted that following the signing of the SPA, the claimant had introduced new conditions. While the respondent had been cooperative in addressing these conditions, they had caused delays in the commencement of the completion phase.

Request for interim measures

The claimant requested an emergency decision that (i) the respondent provide the claimant with the respondent’s latest account statement, and (ii) the respondent preserve an amount equal to the first tranche in its bank account. Alternatively, the claimant requested that (iii) the respondent be ordered to refrain from taking any action aimed at alienating, pledging, charging, selling, or otherwise disposing of assets in an amount equalling the first tranche.

Procedure

The claimant paid the application fee five days before submitting its application for an emergency arbitrator.

The day after the application was filed, the SCC appointed the emergency arbitrator and referred the case. On the same day, the emergency arbitrator contacted the parties to establish a timetable.

The following day, a Friday, the respondent indicated that it would not be able to respond to the application until the following Friday.

On Saturday, the emergency arbitrator requested that the SCC extend the deadline for rendering the emergency award from five to eight days, to allow the respondent to submit its response by Wednesday and the award to be issued on Friday. The SCC granted the extension on the same day.

On Wednesday, the respondent submitted its response to the claimant’s application.

On Friday, the emergency award was rendered – eight days after the referral.

The emergency arbitration was seated in Stockholm, Sweden.

Analysis and decision

First, the emergency arbitrator found that it had jurisdiction. There were no objections from the parties.

The emergency arbitrator then applied the well-established criteria for granting interim relief – risk of irreparable harm, urgency, a reasonable possibility of success on the merits, and proportionality – focusing primarily on the first two.

Concerning irreparable harm, the claimant provided five grounds in support of this risk: (i) the respondent would extract funds from the Company; (ii) the respondent’s major shareholder was suspected of committing crimes; (iii) the respondent conducted business without a proper license; (iv) the respondent did not provide the requested documents after receiving the first tranche; and (v) there was a high risk of the respondent’s insolvency. The emergency arbitrator found that none of the claimant’s arguments had demonstrated sufficient risk or threat that grave or serious harm would occur.

With reference to the lack of a risk of irreparable harm, the emergency arbitrator concluded that the urgency requirement was also not met, noting further that some of the circumstances upon which the claimant relied were known to the claimant prior to entering into the SPA.

Having found that the claimant’s application failed to satisfy the criteria of irreparable harm and urgency, the emergency arbitrator noted that the analysis of the remaining criteria was set forth for the sake of completeness.

The emergency arbitrator concluded, without further elaboration, that the claimant had established a prima facie case on the merits.

Concerning proportionality, the emergency arbitrator found that the claimant’s request (i) was disproportionate, as it would merely provide a snapshot of the respondent’s account without any effect on the future disposition of those funds. However, the emergency arbitrator found that the claimant’s requests (ii) and (iii) were proportionate, as the amount did not exceed a potential future award and the respondent had failed to demonstrate that these measures would negatively affect it.

On the above background, the emergency arbitrator denied all the claimant’s requests for interim relief.

Case 7

Background

The parties, both Swedish entities, entered into an agreement pursuant to which the claimant was granted a right to procure the respondent’s product. Following the conclusion of the agreement but prior to the exercise of the procurement right, the respondent informed the claimant that the claimant no longer satisfied the conditions for exercising that right.

The claimant believed that the respondent had unilaterally altered the conditions set forth in the agreement and that the claimant continued to retain its right to procure the respondent’s product. The claimant therefore asserted that the respondent had breached the agreement.

Upon learning that a third party had procured at least some of the products to which the claimant believed it was entitled to procure, the claimant applied for interim relief.

Request for interim measures

The claimant requested an emergency decision prohibiting the respondent from entering into further agreements with other customers or from taking any other measures in that regard.

Procedure

The SCC appointed the emergency arbitrator and referred the case on the same day it received the application.

The following day, the parties and the emergency arbitrator agreed on a timetable during an online meeting.

Two days after the referral, the respondent submitted its answer to the application.

Three days after the referral, the claimant requested a document from the respondent, and the respondent complied. The same day, the respondent made a further submission.

Four days after the referral, the claimant made a further submission.

The emergency award was rendered five days after the referral.

The seat of the emergency arbitration was Stockholm, Sweden.

Analysis and decision

The emergency arbitrator first stated that established practice dictates that the claimant must demonstrate jurisdiction, that there is a reasonable chance of success in a following arbitration (prima facie case), that there is a risk of irreparable harm, that urgency is needed, and that the interim measure is proportionate.

Next, the emergency arbitrator stated that the threshold for establishing jurisdiction must be lower for emergency arbitrators compared to ordinary tribunals. The emergency arbitrator then found that it had jurisdiction based on the arbitration clause in the agreement. However, it was noted that it was questionable whether the actions could justify the interim measures sought as the field was also publicly regulated.

Concerning irreparable harm, the claimant asserted that the respondent’s continued contracting with other customers would result in the respondent not being able to deliver the product to the claimant, thereby risking irreparable harm. The respondent denied this by stating that the delivery to other customers would not prevent the respondent from delivering to the claimant and that there would be plenty of time to resolve disputes as it would take a long time to deliver the product to any customer.

The emergency arbitrator found that determining whether the claimant or the respondent’s other customers had the right to the product would result in competitive advantages or disadvantages for the respective parties, and that consequently this determination was better suited for the main arbitration.

The emergency arbitrator briefly addressed proportionality, noting that deciding on who had the right to the respondent’s product would result in a proportionality assessment not only between the claimant and the respondent, but also between the claimant and the respondent’s other customers – which fell outside the scope of the emergency arbitration.

As the emergency arbitrator found that the criterion of irreparable harm was not satisfied, no direct assessment of the remaining criteria was undertaken.

On that basis, the emergency arbitrator dismissed the claimant’s requests in their entirety.

Case 8

Background

The Russian claimant and the Swiss respondent entered into two separate EPC contracts under which the respondent undertook to render certain services, and the claimant made two advance payments. The respondent also issued several guarantees, under which a Swiss bank undertook to pay the claimant, provided that several conditions were met.

The project came to a halt shortly after the conclusion of the last contract, and following the institution of “measures in relation to the situation in Ukraine” in Switzerland. After unsuccessful settlement discussions, the claimant called upon the guarantees, asserting that the respondent had unlawfully withheld the advance payments.

The Swiss bank considered the conditions to be met. However, the respondent obtained an injunction from the Swiss national courts preventing the bank from honouring its payment obligation (the claimant asserted that the injunction was obtained ex parte, while the respondent denied that the claimant had been precluded from participating).

Subsequently, the respondent commenced two SCC arbitrations against the claimant based on the two EPC contracts (later consolidated). The respondent sought, inter alia, to prohibit the claimant from calling upon any of the guarantees and to obtain a declaration that the respondent’s contractual obligations had been deferred pursuant to an event of force majeure.

At the time of the emergency arbitration, the consolidated case had not yet been referred to any tribunal.

Request for interim measures

The claimant requested an emergency decision ordering the respondent to request and or consent to a stay of the proceedings pending before the Swiss national courts until a final award was rendered in the main arbitration.

Procedure

On the day the application was received, the SCC notified the respondent.

The following day, the emergency arbitrator was appointed and the case was referred. The emergency arbitrator contacted the parties on the same day to propose a timetable. The respondent also requested an extension of the deadline for submitting its response.

The following day, the emergency arbitrator adjusted the timetable in accordance with the respondent’s request.

Four days after the referral of the case, the respondent submitted its response.

Five days after the referral, the claimant submitted a further written submission, and the respondent submitted an unsolicited rejoinder. The claimant was granted leave to reply, and the respondent was granted leave to respond to the claimant’s reply. Neither party requested a hearing. The emergency award was rendered later the same day.

The seat of the emergency arbitration was Stockholm, Sweden.

Analysis and decision

The emergency arbitrator first rejected the respondent’s objection that the claimant was not duly represented, noting that the representative acted pursuant to a power of attorney and was registered as having the right to represent the claimant even without such authorisation.

The respondent also objected to the emergency arbitrator’s jurisdiction on the basis that the dispute concerned the separate guarantees, which contained their own jurisdiction clauses and to which the claimant was not a party. The emergency arbitrator concluded that he had jurisdiction to hear the dispute, as the relief sought was directed at the respondent rather than the bank or the Swiss courts. However, the emergency arbitrator noted that whether the relief sought should be granted was a separate issue.

The emergency arbitrator observed that although the parties had agreed to resolve disputes arising under the EPC contracts by arbitration under the SCC Rules, the guarantees were subject to the jurisdiction of the Swiss national courts. The emergency arbitrator further noted that had the court proceedings been brought in breach of the arbitration agreements contained in the EPC contracts, this would have been a classic situation for interim relief.

The emergency arbitrator then addressed the “balance of harm”, combining the criteria of irreparable harm and proportionality. Comparing the potential harm of granting versus not granting the interim measure, the emergency arbitrator concluded that the claimant had not demonstrated that it would suffer irreparable harm if the relief sought were not granted.

Having reached a conclusion on the foregoing grounds, the emergency arbitrator did not consider it appropriate to express any view on the claimant’s possibility of success in the underlying arbitration.

The emergency arbitrator did not directly address the criterion of urgency.

On the above background, the emergency arbitrator denied all the claimant’s requests for interim relief.

Case 9

Background

The dispute concerned the acquisition of several construction projects. In connection therewith, the Swedish parties concluded two share purchase agreements (SPAs) under which the claimant acquired all shares in two companies. Following the acquisition, the claimant transferred the shares to a different company within its own group, and the boards of directors in both acquired companies were replaced.

Construction later came to a halt, and a dispute arose concerning payment of the purchase sum and the ownership of the two companies. The claimant claimed that the second tranche of the purchase sum was not yet due. The respondent contested this. As a result, the respondent believed the SPAs to be null and void and consequently acted to, inter alia, replace the boards of directors of the two companies to take back control – an act the claimant considered to be unlawful. In addition, the respondent believed the transfer of the shares to a different company within the claimant’s group to constitute a breach of contract, and that consequently the respondent was entitled to terminate the SPAs.

Request for interim measures

The claimant requested an emergency award establishing that (i) the respondent was not a shareholder of the two companies, (ii) the claimant’s replacement of the boards of directors was valid, (iii) the respondent’s replacement of the boards of directors was invalid, and (iv) the respondent was prohibited from acting on behalf of the companies or exercising rights that would follow from being a shareholder and that such actions would be fined.

Procedure

The SCC appointed the emergency arbitrator and referred the case the day after receiving the application. A timetable was agreed during an online meeting held on the same day.

Two days after the referral, the respondent submitted its response to the application.

Three days after the referral, the claimant made a further written submission.

The emergency award was rendered five days after the referral of the case to the emergency arbitrator.

Analysis and decision

First, the emergency arbitrator noted that both SPAs contained arbitration clauses referring to the SCC, and that no objections were made, consequently concluding that it had jurisdiction.

Next, the emergency arbitrator stated that it was undisputed that the claimant no longer held ownership of the shares in the two companies.

The emergency arbitrator then stated that as a starting point, the questions of whether the SPAs were validly terminated, and whether the return of the shares to the respondent was a valid remedy, were matters to be determined in the main arbitration.

The emergency arbitrator observed that the SCC Rules did not specify conditions for the granting of interim measures and that an emergency arbitrator enjoyed a broad discretion in that regard. The emergency arbitrator also noted that the applicant must demonstrate, inter alia, a prima facie case on the merits, a risk of irreparable harm, and proportionality.

The emergency arbitrator then stated that the claimant had demonstrated a prima facie case but not a risk of irreparable harm before expanding on the latter. Here it noted that within the prima facie assessment, it was not possible to determine whether the claimant had acquired the shares through a subsidiary and thereby transferred the rights and obligations to a different company within the corporate group. Therefore, it was not possible to assess the claimant’s interest in the two companies. While it could not be excluded that the claimant had an interest in the interim measures, the emergency arbitrator stated that it could not be concluded that the claimant had retained sufficient interest therein. In addition, it was unclear to the emergency arbitrator what harm the claimant would suffer.

On this basis, the emergency arbitrator denied all the claimant’s requests for interim measures.

With respect to the claimant’s request (iv), the emergency arbitrator further noted that, pursuant to the applicable law, arbitrators – including emergency arbitrators – do not, as a general rule, have the authority to impose liquidated damages in connection with an emergency decision.

Investment disputes and the fees of the emergency arbitrator

In addition to the commercial arbitrations discussed above, the SCC also received two applications for the appointment of an emergency arbitrator in investment disputes during the period. Due to the limited number of investment arbitration cases and to preserve their confidentiality in accordance with the SCC Rules, these cases are not elaborated upon in detail in this SCC Practice Note.

For the sake of completeness, the first application for the appointment of an emergency arbitrator in an investment dispute in the relevant time period was dismissed as the emergency arbitrator concluded that it lacked jurisdiction.

The second such application during the period was granted in part. Notably, this case marked the first occasion in which the SCC increased the fee of an emergency arbitrator.

Pursuant to Art. 10 (3), Appendix II of the SCC Rules:

“At the request of the emergency arbitrator, or if otherwise deemed appropriate, the Board may decide to increase or reduce the costs set out in paragraph (2) (i) and (ii) above, having regard to the nature of the case, the work performed by the emergency arbitrator and the SCC and any other relevant circumstances.”

Pursuant to Art. 10 (2), Appendix II of the SCC Rules:

“The costs of the emergency proceedings include:

(i) the fee of the emergency arbitrator, in the amount of EUR 16 000;

(ii) the application fee of EUR 4 000; and

(iii) the reasonable costs incurred by the parties, including costs for legal representation.”

In the second case, the emergency arbitrator requested the Board to increase the fee of the emergency arbitrator as the proceedings had been “exceptionally extensive and required a high amount of work […]”.

Prior to the issuance of the emergency award, the parties submitted a combined total of four written submissions (totalling 115 pages), 132 factual exhibits, 90 legal exhibits, and a timeline that was subsequently updated. Following the award, a supplement to the emergency award was requested, prompting the submission of a further two written submissions (totalling 28 pages), 15 additional factual exhibits, one resubmitted legal exhibit, 28 new legal exhibits, and a further update to the timeline.

Given the amount of work and in particular the fact that the emergency arbitrator rendered a supplement to the emergency award, the SCC decided to grant the emergency arbitrator’s request and increased the fee paid.

Reflecting on 15 years of emergency arbitration at the SCC

A review of the jurisprudence on emergency arbitration at the SCC indicates that the 2023–2025 period signals a return to normal, with further consolidation of the well-recognised standards for granting interim relief.

Rates of success

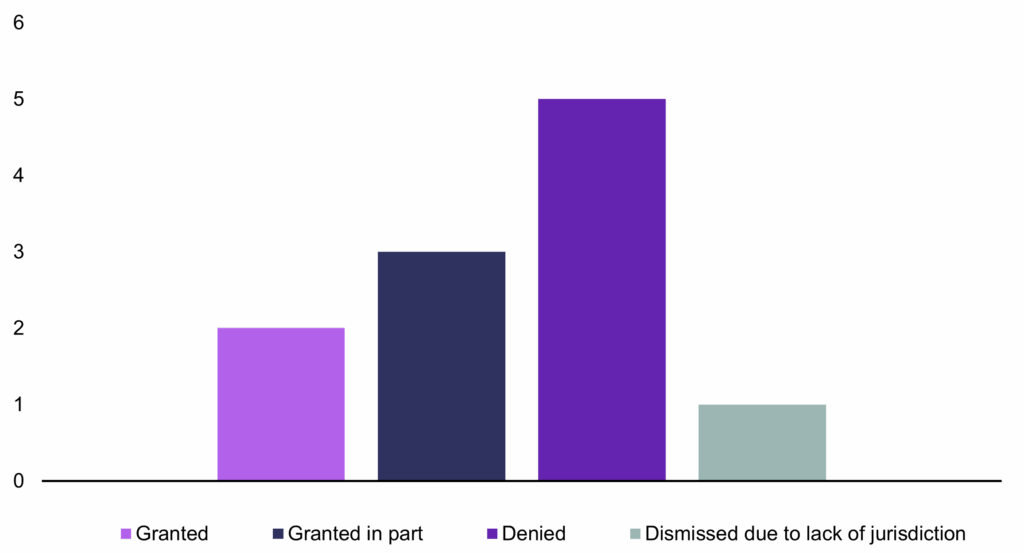

In 2023 and 2024, the SCC received four applications for emergency arbitration per year, while it received three in 2025. Out of the 11 applications, two were granted, three were granted in part, five were denied, and one was dismissed due to lack of jurisdiction.

These numbers demonstrate that, despite a higher success rate in 2019–2022,10 it remains difficult for claimants to succeed in emergency arbitrations – a testament to the high standards applied by emergency arbitrators. The risk of irreparable harm continues to be the most challenging criterion to establish, followed by urgency, whilst the claimants often succeed in demonstrating a prima facie case.

Time to a decision

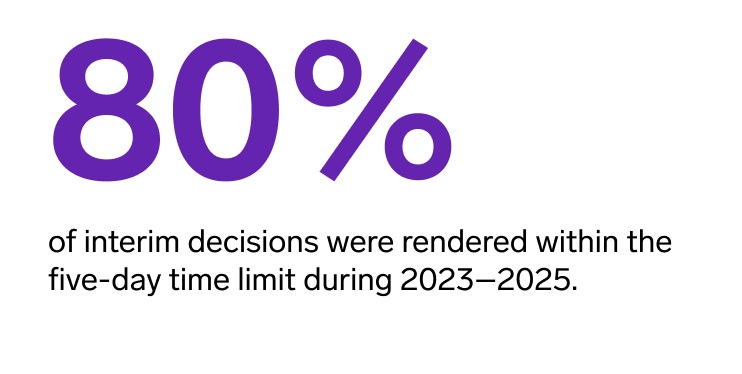

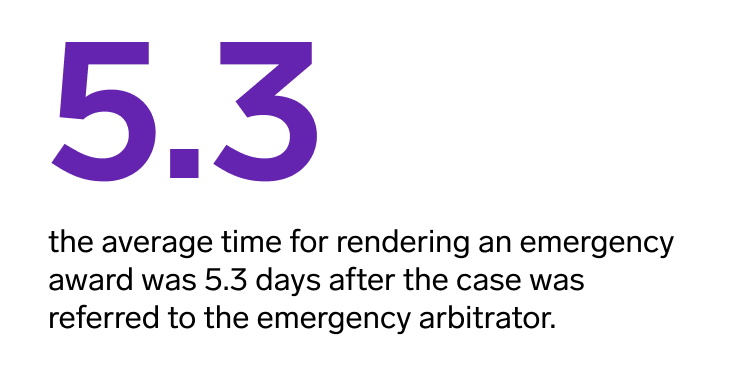

As to the timelines of the proceedings, the 2023–2025 period saw a reversal of some trends from the previous period. Whilst during the 2019–2022 period only 54% of interim decisions were rendered within the five-day time limit, this number increased to 80% (8 out of 10 cases) in 2023–2025, with one decision rendered in four days. In the two cases where the five-day deadline was not met, an extension of the deadline to six and eight days, respectively, was granted. As such, the average time for rendering an emergency award was 5.3 days after the case was referred to the emergency arbitrator. This demonstrates the efficiency of the emergency arbitrator mechanism under the SCC Rules.

Nationality

Between 2023-2025, parties from 11 different countries participated in applications for the appointment of emergency arbitrator under the SCC Rules, and emergency arbitrators of six different nationalities were appointed. Seven out of the ten cases were international, meaning that at least one party was not Swedish, while the remaining three were domestic Swedish disputes.

While 2023–2025 may signal a shift back towards the long-term norm, it is important to remember that the appointment of an emergency arbitrator remains relatively rare, and the small number of cases can make it difficult to draw conclusions.

Criteria assessed

All but one emergency arbitrator in 2023–2025 found that they had jurisdiction.11 In one case, court proceedings had been initiated before the application for emergency arbitration, however, the emergency arbitrator found that because the claimant in the emergency arbitration had objected to the court proceedings and had not presented any submissions, the emergency arbitrator retained jurisdiction. Further, it was held by one emergency arbitrator that the threshold for establishing jurisdiction in an emergency arbitration is lower than in a standard arbitration.

Moreover, only one emergency arbitrator found that the claimant had failed to establish a prima facie case, and this finding pertained only to part of the requested relief. However, not all emergency arbitrators assessed this criterion. Several stated that because other criteria were not satisfied, it was unnecessary to address the claimant’s prima facie case, while others found it inappropriate to do so or omitted to comment on this criterion altogether.

Of the remaining criteria – the risk of irreparable harm, urgency, and proportionality – the risk of irreparable harm was by far the criterion that emergency arbitrators found satisfied the least. In six cases, no such risk was established. One emergency arbitrator held that “serious or substantial harm” would satisfy the criterion, while several others found that the decisive factor was whether the harm could be compensated through damages awarded in a subsequent arbitration. A risk of irreparable harm was found to exist in three cases.12

Urgency was found to be present in three cases, absent in three, and not addressed in three. Meanwhile, proportionality was found to be present in three cases, missing in two, and not addressed in four.13

Conclusion

As the SCC marks 15 years of emergency arbitration and almost 70 applications, the mechanism has proven to be a reliable and efficient tool for parties seeking urgent interim relief. This has been the case both in the commercial and investment arbitration contexts.

The 2023–2025 period confirms that while obtaining emergency relief remains challenging, the process continues to deliver timely decisions, with 80% of awards rendered within the five-day limit, while maintaining rigorous standards. Looking ahead, the SCC remains committed to providing parties with access to swift and effective dispute resolution, including emergency arbitration proceedings.

Notes

1 Jake is a dual-qualified lawyer (Australia & Sweden) and Specialist Counsel at the SCC Arbitration Institute (SCC). Frederik is an Associate at Danish law firm Gorrissen Federspiel in Copenhagen and former Intern at the SCC.

2 See https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/our-services/emergency-arbitrator/.

3 Article 1(1) Appendix II of the SCC Rules.

4 Articles 3 and 4(1) Appendix II of the SCC Rules.

5 See https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/our-services/emergency-arbitrator/.

6 Article 8(1) Appendix II of the SCC Rules.

7 Article 9(1) and (4) Appendix II of the SCC Rules.

8 Articles 37(1)-(3) of the SCC Arbitration Rules and 38(1)-(3) of the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitration cf. article 1(2) Appendix II of the SCC Rules.

9 See https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/our-services/emergency-arbitrator/ and SCC Practice Note, Emergency Arbitrator Decisions rendered 2019-2022, SCC Practice Note, Emergency Arbitrator Decisions rendered 2017-2018, SCC Practice Note, Emergency Arbitrator Decisions rendered 2015-2016, SCC Practice Note, Emergency arbitrators in investment treaty disputes at the SCC 2014-2019, SCC Practice Note, Emergency Arbitrator Decisions Rendered 2014, SCC Practice Note, Emergency Arbitrator Decisions.

10 In 2019-2022, out of 22 applications received, eight requests were granted in full, three were granted in part, ten were denied, and one was dismissed due to lack of jurisdiction.

11 The only case where the emergency arbitrator found it did not have jurisdiction was in an investment dispute.

12 Emergency decisions in investment disputes are excluded from this statistic.

13 Emergency decisions in investment disputes are excluded from these statistics.