SCC Practice Note: SCC Board decisions on challenges to arbitrators 2020–2024

Authors: Yi Ting Sam and Raffaela Isepponi1

Table of contents

Introduction

Stockholm and the SCC Arbitration Institute (“SCC”) are routinely mentioned and referenced as one of the key venues and players both in commercial and investment arbitration.2 The SCC maintains two main sets of arbitration rules, the SCC Arbitration Rules and the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules (together, the “SCC Rules”).

The SCC Rules provide for a procedure in line with the best practices in international arbitration. The SCC Rules stipulate (as do most institutional rules) that arbitrators must be impartial and independent, and provide an avenue for parties to challenge an arbitrator where circumstances exist that give rise to justifiable doubts as to an arbitrator’s impartiality or independence. In line with the principle of party autonomy, the SCC Rules also stipulate that parties may challenge an arbitrator if the arbitrator does not possess the qualifications agreed by the parties, though challenges based on this ground are relatively rare.3

The practice note is structured as follows:

Section 2 discusses the SCC procedure for challenges to arbitrators.

Section 3 analyses the applicable legal standard that applies to challenges to arbitrators in cases administered by the SCC. This section builds upon the observations made in previous SCC publications regarding challenges to arbitrators,4 and discusses some new developments in this area.

Section 4 comments on the statistics on challenges.

The challenge decisions rendered by the SCC Board (“Board”) from 2020 to 2024 are summarised in Sections 5 to 8, categorised by the primary basis of the challenge. Some of the background facts have been slightly altered for reasons of confidentiality. In some cases, the reasons have been omitted, in full or in part, also to preserve confidentiality.

Section 5 summarises the decisions on challenges based on the arbitrator’s alleged relationship with a party, counsel, and/or others involved in the arbitration.

Section 6 summarises the decisions on challenges based on the arbitrator’s conduct during the arbitral proceedings.

Section 7 summarises the decisions on challenges based on alleged breaches of confidentiality / political statements.

Section 8 summarises the decisions on challenges based on the arbitrator’s nationality / qualifications.

Section 9 sets out some conclusions that may be drawn from the challenge decisions summarised in this practice note.

The SCC procedure for challenges to arbitrators

The SCC is composed of a Secretariat, a Board, the SCC Arbitrators’ Council, and the SCC Council for Swedish Arbitration. The Secretariat provides a trained staff for administration of cases and assists in the Board’s decision making. The board members, half of which are international, convene monthly and as needed to make decisions in accordance with the applicable rules – including decisions on challenges to arbitrators. The SCC Arbitrators’ Council and the SCC Council for Swedish Arbitration are not involved in the handling of the arbitrations at the SCC.

The formal requirements for a challenge are set out at Article 19(3) of the SCC Arbitration Rules and Article 20(3) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules. Under these provisions, a party who wants to challenge an arbitrator must submit a written statement to the Secretariat setting forth the reasons for the challenge. The challenge must be filed within 15 days from when the circumstances giving rise to the challenge became known to the party. Failure by a party to challenge an arbitrator within the stipulated time constitutes a waiver of the right to make the challenge, and the Board can dismiss a challenge on this ground even where other grounds exist to sustain the challenge.

In this connection, it bears mention that arbitrators have a continuing obligation to disclose any circumstances that may give rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence. Prospective arbitrators are required to make such disclosures prior to their appointment pursuant to Article 18(2) of the SCC Arbitration Rules and Article 19(2) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules. Once appointed, arbitrators are also required to submit a signed statement of acceptance, availability, impartiality, and independence setting out any such disclosures pursuant to Article 18(3) of the SCC Arbitration Rules and Article 19(3) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules. In practice, the SCC typically provides this statement to the arbitrator for signature and subsequently circulates the signed statement to the parties. An arbitrator’s duty of disclosure continues throughout the course of the arbitration, as stipulated in Article 18(4) of the SCC Arbitration Rules and Article 19(4) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules.

The SCC aims to handle all challenges to arbitrators efficiently, to avoid delaying the arbitral proceedings. In line with Article 19(4) of the SCC Arbitration Rules and Article 20(4) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules, arbitrators and opposing parties are typically given one week to comment on the challenge. The challenging party may, if necessary, get a further opportunity to respond. If all parties agree to the challenge, the arbitrator must resign in accordance with Article 19(5) of the SCC Arbitration Rules and Article 20(5) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules. In all other cases, the Board shall make the final decision on the challenge. Where the arbitrator offers to voluntarily step down in response to a challenge, the Board typically decides to release the arbitrator.

If the Board sustains the challenge, the arbitrator is released from their appointment under Article 20(1)(ii) of the SCC Arbitration Rules or Article 21(1)(ii) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules (as the case may be). In addition, the Board may also release an arbitrator where “the Board accepts the resignation of the arbitrator” or “the arbitrator is otherwise unable or fails to perform the arbitrator’s functions” under Article 20(1)(i) and (iii) of the SCC Arbitration Rules respectively.

The same applies under Article 21(i) and (iii) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules. Arbitrator resignations are most frequently prompted by a challenge raised against the arbitrator. As such, even though arbitrator resignations and successful challenges constitute independent grounds warranting the release of an arbitrator, they are often interrelated in practice.5

Pursuant to Article 19(5), the Board’s decisions on challenges are final and thus not subject to review by local courts except where permitted by the lex arbitri. Insofar as Swedish law is the lex arbitri, it should be noted that even though Section 10 of the Swedish Arbitration Act provides for an avenue of appeal where the challenge was dismissed, parties may nonetheless agree that a challenge to an arbitrator be “conclusively determined” by an arbitration institution instead pursuant to Section 11 of the Swedish Arbitration Act.6

To assist the Board in deciding challenges, the Secretariat prepares a memorandum for the Board upon receipt of a challenge. This memorandum commonly includes the grounds for challenge, comments submitted by the arbitrators and parties, and an analysis of the circumstances based on SCC precedent, legal authorities, and the IBA Guidelines. Typically, the Board discusses the challenge at the next monthly meeting, or in exceptional situations at an extraordinary board meeting. The Board usually reaches a decision by consensus, but in difficult cases, the decision is made by majority vote.

Prior to 1 January 2018, the parties and arbitrators would be informed only whether the Board had sustained or dismissed the challenge. Since 1 January 2018, the SCC provides reasons for sustaining or dismissing a challenge.7 While the SCC Rules do not oblige the Board to provide reasons, a policy was introduced to this effect in response to user requests and in light of the general trend toward greater transparency in arbitration.8 As a main rule, the reasons provided to the parties are brief but may be more extensive if warranted by the circumstances of a particular challenge. The outcome of the decision and the underlying reasons are only shared with the parties and the other arbitrators (if any) and not published by the SCC. Anonymised versions of such decisions are made public solely through SCC practice notes, such as this one.

The applicable legal standard

The SCC Rules

As a general point, Article 18 of SCC Arbitration Rules mandates that every arbitrator must be impartial and independent and sets out the disclosure requirements of arbitrators. Equivalent provisions for expedited arbitrations are set out at Article 19(1) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules.

Challenges to arbitrators are governed under Article 19 of the SCC Arbitration Rules. Article 19(1) of the SCC Arbitration Rules provides that: “[a] party may challenge any arbitrator if circumstances exist that give rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence or if the arbitrator does not possess the qualifications agreed by the parties”. Similarly, Article 20(1) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules provides that a party may challenge the arbitrator for the same reasons. These provisions have been in force since 20179 and remain unchanged in the 2023 revision of the SCC Rules save for minor linguistic amendments.

Neither set of rules expressly define what constitutes “justifiable doubts” or explain the circumstances that may legitimately give rise to such doubts. In line with previous practice, the Board has consistently looked to the applicable law and best practices in international arbitration for guidance when determining whether a challenge filed under these provisions should be sustained.

Further, Article 19(2) of the SCC Arbitration Rules stipulates that a party may challenge an arbitrator it has appointed or in whose appointment it has participated, only for reasons of which it has become aware after the appointment. This provision aims at preventing obstructing parties from deliberately appointing an arbitrator with a known conflict or lack of qualification for the purpose of subsequently raising a challenge and sabotaging the constitution of the Arbitral Tribunal.10 The same applies under Article 20(2) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules.

The UNCITRAL Rules

Where the SCC has been designated as an appointing authority under the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules, the Board may also decide challenges under these rules.

Similar to the SCC Rules, the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules11 stipulate that “[a]ny arbitrator may be challenged if circumstances exist that give rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence” and does not expressly define what constitutes “justifiable doubts”. As such, when deciding a challenge on this ground under the UNCITRAL Arbitral Rules, the Board may adopt the same approach that would typically apply to a similar challenge under the SCC Rules.

During the time period which this practice note covers, the SCC rendered two challenge decisions in ad hoc arbitrations where the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules applied.12 In both those cases, the SCC was designated as the appointing authority. Decisions on challenges are among the various comprehensive ad hoc arbitration services provided by the SCC. These services may be used in all forms of ad hoc arbitration, including those not governed by the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules.

Arbitrations seated in Sweden

Where the seat of arbitration is in Sweden, Swedish law is the lex arbitri (i.e., the law governing the arbitral proceedings). Under Swedish law, the applicable legislation is the Swedish Arbitration Act.13 In addition, Swedish court decisions interpreting the Swedish Arbitration Act are of particular relevance to arbitrations administered by the SCC that are seated in Sweden, as they provide guidance on how Swedish courts approach issues of arbitrator impartiality and independence.

The Swedish Arbitration Act

From 2020 to 2024, most of the challenges arose from arbitrations which had their legal seat in Sweden, rendering the Swedish Arbitration Act applicable to the proceedings. In this period, most of the decisions taken by the Board were governed by the version of Swedish Arbitration Act which came into force on 1 March 2019.14

Section 7 of the Swedish Arbitration Act bars anyone not vested with full legal capacity in relation to their actions and property from acting as arbitrator. This provision is mandatory and thus applies to all arbitrations seated in Sweden.15

Section 8 of the Swedish Arbitration Act states that “[i]f a party so requests, an arbitrator shall be released from appointment if there exists any circumstance that may diminish confidence in the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence”. The word “independence” was added to Section 8 when the Act was revised in 2019. That said, this addition has not altered the intended application of Section 8 as the “impartiality” requirement under the previous version of the Act encompassed the “independence” standard.16

Section 8 of the Swedish Arbitration Act provides a non-exhaustive list of circumstances which always should be deemed to diminish confidence in the arbitrator’s impartiality, namely:17

(1) if the arbitrator or a person closely associated with the arbitrator is a party, or otherwise may expect noteworthy benefit or detriment as a result of the outcome of the dispute;

(2) if the arbitrator or a person closely associated with the arbitrator is the director of a company or any other association which is a party, or otherwise represents a party or any other person who may expect noteworthy benefit or detriment as a result of the outcome of the dispute;

(3) if the arbitrator, in the capacity of expert or otherwise, has taken a position in the dispute, or has assisted a party in the preparation or conduct of its case in the dispute; or

(4) if the arbitrator has received or demanded compensation in violation of the second paragraph of Section 39 the Act (which relates to agreements regarding compensation to the arbitrators).

Section 9 of the Swedish Arbitration Act requires arbitrators to disclose all circumstances which may diminish confidence in their impartiality or independence, and Section 10 and 11 of the Swedish Arbitration Act regulates the procedure for challenges to arbitrations under Swedish law.

Swedish case law

The Supreme Court of Sweden has held that, because arbitral awards cannot be challenged on the merits, the standard for arbitrators’ impartiality is necessarily a high one. An arbitrator’s impartiality should be assessed objectively: if a situation or a relationship exists that would normally lead to the conclusion that the arbitrator is not impartial, the challenged arbitrator should be dismissed even if there is no reason to assume that he or she will lack impartiality in the specific dispute at hand.18

The Svea Court of Appeal has held (and the Supreme Court has affirmed) that the decision on whether to sustain a challenge to an arbitrator should be based on an “overall assessment taking all relevant circumstances into consideration”.19 In other words, even if one circumstance is not sufficient to doubt the challenged arbitrator’s impartiality, a number of individually rather marginal circumstances may lead the decision-maker to a different conclusion.20

In the above-mentioned cases, the Supreme Court also provided some guidance on the implications of failure to disclose information that may give rise to doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality. In particular, the Supreme Court’s reasoning in these cases may imply that failure to disclose such circumstances does not, in and of itself, constitute independent grounds for challenge.21

Allegations concerning arbitrators’ lack of impartiality and independence have come before the Swedish courts on numerous occasions. The facts of some of the more notable cases are summarised below:

(a) In Anders Jilkén v. Ericsson AB,22 the Supreme Court of Sweden set aside an arbitral award because the chairperson’s impartiality had been objectively undermined by the fact that the arbitrator had been employed by the law firm representing the respondent, noting that this relationship was of commercial importance to the law firm.

(b) In Korsnäs AB v. AB Fortum Värme samägt med Stockholms stad,23 the Supreme Court of Sweden refused to set aside an arbitral award on the basis that the party-appointed arbitrator’s prior appointments by the same law firm raised doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality. In particular, the Supreme Court noted that in the ten-year period preceding the appointment in question, the prior appointments only accounted for approximately ten percent of the arbitrator’s total appointments. This was too minimal to undermine the arbitrator’s appearance of impartiality.

(c) In KPMG v. ProfilGruppen,24 the Svea Court of Appeal set aside an arbitral award as the law firm of one of the arbitrators had accepted a client in a matter against one of the parties in the arbitration. Applying an objective test, the court concluded that circumstances existed to raise justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality, irrespective of whether the arbitrator had known that his firm had accepted those instructions.

(d) In Tidomat v. Relacom,25 the Svea Court of Appeal refused to set aside an arbitral award based on a challenge that the arbitrator had previously done work for an alleged affiliate of one of the parties in the arbitration. The court found that the relationships in question were limited and dated back a long time and therefore did not diminish confidence in the arbitrator’s impartiality.

(e) In Australian Media Properties Pty Ltd v. Bonnier International Magazines AB,26 the Svea Court of Appeal refused to set aside an arbitral award on the basis that the arbitrator appointed by the respondent and the chairperson lack impartiality and independence.

The court noted, amongst other things, that the arbitrator appointed by the respondent had only produced legal opinions and testified as expert witness, and did not act as legal counsel or advisor to the alleged affiliate of the respondent.

(f) In Kolboda Mat och Dryck AB (in liquidation) v. Naked Juicebar AB, the Svea Court of Appeal refused to set aside an arbitral award on the basis that the sole arbitrator jointly ran and owned a law firm with a colleague, who in turn had worked at the same law firm as one of the parties’ counsel. In coming to its decision, the court noted that the arbitrator’s colleague had left the law firm in question approximately 14 years before the arbitration proceedings began.27

Arbitrations seated in Finland, Denmark, and Norway

Arbitrations seated in Finland, Denmark, and Norway are governed by their respective national arbitration laws as the lex arbitri. The SCC, as the major arbitration institute in the Nordics, regularly administers arbitrations seated in these jurisdictions, in particular, Helsinki, Copenhagen, and Oslo.

Under Finnish law, Section 10 of the Finnish Arbitration Act28 provides that an arbitrator can be challenged by a party if he/she would have been disqualified to handle the matter as a judge or if circumstances exist that give rise to justifiable doubts as to his/her impartiality or independence.29

Under Danish law, Section 12(2) of the Danish Arbitration Act 200530 provides that an arbitrator may be challenged only if circumstances exist that give rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence, or if the arbitrator does not possess qualifications agreed to by the parties. A party may challenge an arbitrator appointed by him or her, or in whose appointment he or she has participated, only for reasons of which he or she becomes aware after the appointment has been made.31

Similarly, Section 14 of the Norwegian Arbitration Act (“NAA”)32 provides that an arbitrator may only be challenged if there are circumstances that give rise to justifiable doubts about his/her impartiality or independence or if he/she does not possess the qualifications agreed on by the parties. A party may challenge an arbitrator in whose appointment that party has participated only for reasons of which he/she became aware after the appointment was made.33

Of recent significance is a decision by the Supreme Court of Norway issued on 19 May 2025,34 where an appeal to set aside an arbitral award due to the alleged lack of impartiality of one of the arbitrators was dismissed. The basis of the impartiality challenge was that the law firm where the arbitrator was partner had an ongoing engagement with one of the parties to the arbitration during the arbitration proceedings. The Supreme Court first noted that the threshold for disqualification of arbitrators is largely the same as that which applies to judges, though deviations may occur where justified by the particular features of arbitration or by the goal of achieving a unified international practice.

Taking guidance from the IBA Guidelines and Norwegian case law, the Supreme Court found that an arbitrator will generally be identified with the law firm where he or she is employed, even if the client relationship is handled by other advocates in the law firm. That said, there may be grounds for departing from this principle if the engagement is of a more limited nature. In addition, a breach of the arbitrator’s duty of disclosure under Section 14(1) of the NAA will generally only have an independent impact on the outcome of an impartiality assessment in borderline cases.

On the facts, the Supreme Court found that the client relationship in question did not provide sufficient grounds for doubting the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence. Among other factors, the Supreme Court noted that the client relationship in question was sporadic and generated insignificant fees (of NOK 1.9 million) in relation to the arbitrator’s law firm’s overall operations (with a turnover exceeding NOK 1 billion), and that there was an absence of any points of connection between the arbitrator and the client relationship. Although the arbitrator failed to comply with his duty of disclosure, this was not decisive.

The IBA Guidelines on Conflicts of Interest

Since its issuance in 2004, the IBA Guidelines on Conflicts of Interest in International Arbitration (“IBA Guidelines”) have gained wide acceptance within the international arbitration community.35 Arbitrators commonly rely on the IBA Guidelines when making decisions about prospective appointments and necessary disclosures, and the IBA Guidelines are frequently cited in challenges. The Board also routinely consults the IBA Guidelines when deciding challenges. Furthermore, the Supreme Court of Sweden has noted that it may consider the IBA Guidelines – especially in cases involving non-Swedish parties – in making decisions on challenges to arbitrators under the provisions in the Swedish Arbitration Act.36

The IBA Guidelines as updated on 25 May 2024 (“IBA Guidelines 2024”) comprise of two parts: (a) Part I which sets out general standards regarding impartiality, independence, and disclosure; and (b) Part II which sets out a list of specific examples that illustrate these general standards, in the form of a “traffic light system”. The lists are designated as “Red”, “Orange” and “Green” – for situations in which a conflict of interest is commonly understood to exist, in which a conflict of interest may exist depending on the facts and circumstances of the case, and in which a conflict of interest is commonly understood not to exist, respectively.37

It is essential that the two parts of the IBA Guidelines always be read together. The general standards in Part I provide essential principles that must be applied to all situations, which are divided into seven categories. General Standard 1 sets out the fundamental tenet that every arbitrator shall be impartial and independent of the parties from the time of appointment to the termination of the proceedings. General Standard 2 sets out principles to assist with the assessment of whether a particular arbitrator may suffer from a conflict of interest, clarifying, amongst other things, that “[d]oubts are justifiable if a reasonable third person, having knowledge of the relevant facts and circumstances, would reach the conclusion that there is a likelihood that the arbitrator may be influenced by factors other than the merits of the case as presented by the parties in reaching the arbitrator’s decision”.38 General Standard 3 provides guidance on an arbitrator’s duty of disclosure, and General Standard 4 regulates waivers by the parties regarding circumstances that might otherwise constitute a conflict of interest. General Standard 5 defines the scope of the IBA Guidelines, affirming their broad applicability to all tribunal members, as well as arbitral secretaries and assistants. General Standard 6 provides that the existence, or otherwise, of relationships is core to the arbitrator’s independence and impartiality. Finally, General Standard 7 elaborates on the parties’ duty to disclose relationships with the arbitrator, as well as the arbitrator’s corresponding duty to make reasonable enquiries to identify any conflict of interest.39

The lists in Part II describe practical applications of these general standards, and deal with some of the varied situations that commonly arise in practice. The lists are illustrative and non-exhaustive, and the absence of a particular situation does not necessarily indicate that no disclosure must be made, much less that any conflict of interest does or does not exist.40

The Board routinely references the IBA Guidelines when assessing whether a circumstance, relationship or situation invoked as a ground for challenge gives rise to “justifiable doubts” as stipulated by the SCC Rules. That said, the Board conducts a holistic assessment of the circumstances in each individual case and retains the discretion to look beyond the specific examples set out in the lists at Part II of the IBA Guidelines, especially where the facts in question do not fall squarely within the non-exhaustive list of examples set out therein.

Statistics

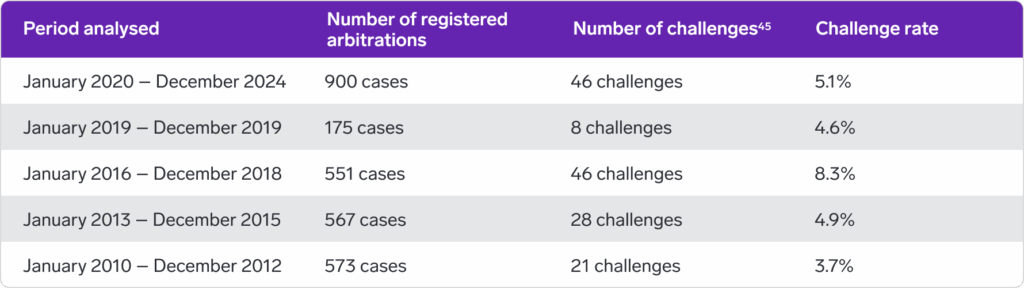

Between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2024, the Board issued 46 decisions on challenges. In several arbitration cases, the Board issued more than one challenge decision. In five arbitration cases, a party challenged the arbitrator twice.41 In one arbitration case, the same arbitrator was challenged three times.42

Additionally, on two instances, the Board issued separate challenges in related cases. In the first instance, the Board issued six separate challenge decisions in six related arbitration cases.

In the second instance, the Board issued two separate challenge decisions in two related arbitration cases. Insofar as the challenge decisions were issued in related cases, these are summarised together in the next section.43

The practice note excludes cases in which a challenge was made but no decision was rendered by the Board. For example, where the arbitrator voluntarily stepped down, the case was dismissed before a decision was rendered (for example, if the parties reached a settlement), or the challenge was withdrawn.

Of the 46 challenge decisions, the following statistical trends can be observed:

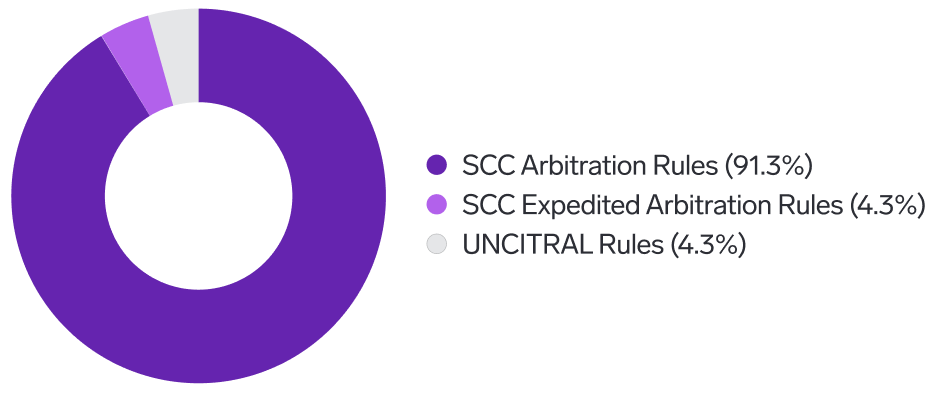

- 42 of the challenges concerned the SCC Arbitration Rules (around 90%), 2 the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules (around 5%), and 2 the SCC Procedures for Acting as Appointing Authority under the UNCITRAL Rules (around 5%).

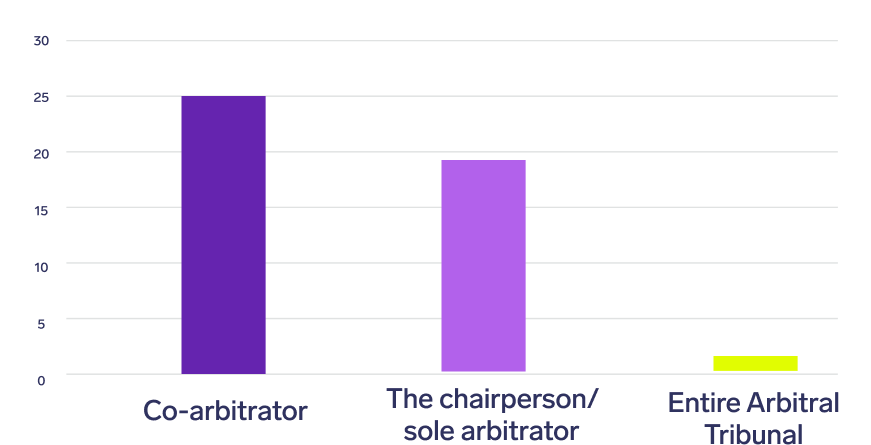

- 25 of the challenges concerned a co-arbitrator (around 54%), 19 the chairperson/sole arbitrator (around 41%), and 2 concerned the entire Arbitral Tribunal (around 5%).

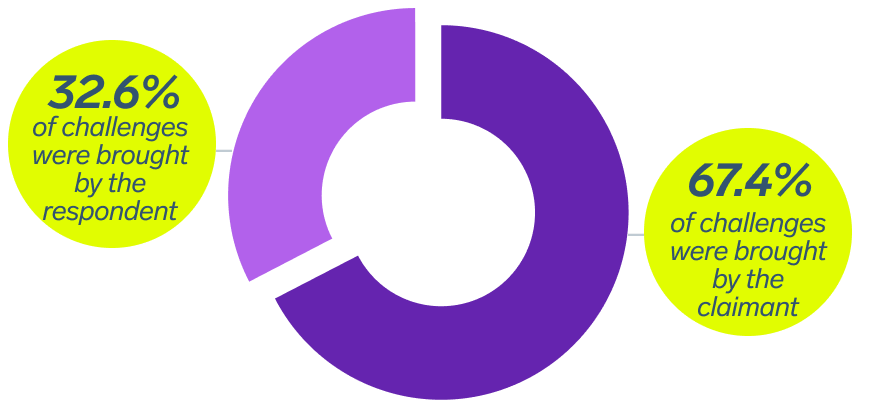

- 31 of the challenges were brought by the respondent (around 67%) and 15 of the challenges were brought by the claimant (around 33%).

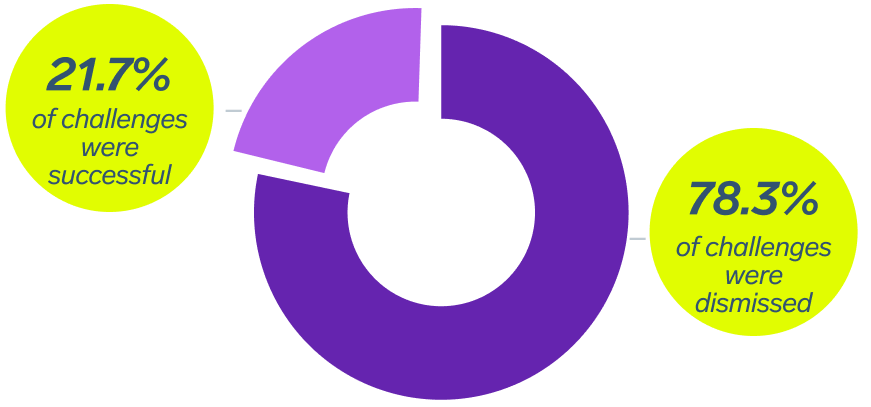

- 10 of the challenges were successful (around 22%) and 36 challenges were dismissed (around 78%).

Further, with reference to previously published statistics,44 the following comparisons can be made:

Challenges based on the arbitrator’s alleged relationship with a party, counsel, and/or others involved in the arbitration

Between 2020 and 2024, the majority of the challenges centred around allegations that there were circumstances that may give rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence due to relationships between the arbitrator and one of the parties, their affiliates, or their counsel.

Most of these challenges were brought on the basis that the arbitrator had a relationship with the counterparty to the challenge, for example, whether the arbitrator worked or previously worked at the same law firm as the counterparty’s counsel, or had been previously appointed as arbitrator by the counterparty or their counsel in other arbitrations.

A number of cases concerned the opposite scenario, where it was alleged that the arbitrator had a hostile or adverse relationship with the challenging party or their counsel, or had acted against that party or its affiliates in some capacity.

Relationships between the arbitrator and the counterparty or their counsel etc.

Case 1 (challenge dismissed)46

The claimant challenged the sole arbitrator on the basis that the arbitrator worked at the same law firm as the respondent’s newly appointed counsel about two and half years before the challenge was made.

The Board dismissed the challenge, noting that the respondent’s new counsel was only employed for a short period of time at the law firm in question, and predominantly worked with cases in which the arbitrator was not involved in.

Case 2 (challenge dismissed)47

The claimant challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the respondent, alleging that there was a conflict of interest because the arbitrator and the respondent’s counsel had previously acted as counsel for the same party in a separate matter which was unrelated to the arbitration proceedings.

The Board dismissed the challenge, noting that while the arbitrator and the respondent’s counsel had represented the same client, they did not do so at the same time. Moreover, the comments from the arbitrator and the respondent’s counsel demonstrated that the case did not involve the type of cooperation referred to in §3.3.9 of the Orange List in the IBA Guidelines 2014, namely, where the arbitrator and counsel for one of the parties’ counsel are co-counsel.48

Case 3 (challenge dismissed)49

The claimant challenged the sole arbitrator based on the previous appointments by and connections with the respondent’s former counsel.

The Board dismissed the challenge, noting that the respondent had revoked its power of attorney for its former counsel prior to the arbitrator’s appointment in the case at hand.

Case 4, Case 5, Case 6, Case 7, Case 8, and Case 9 (six challenges, all dismissed)50

Six separate challenges were brought in six arbitrations involving the same contract and the same parties. In all six instances, the respondent challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the claimant on the three grounds: Firstly, the same arbitrator was appointed by the claimant in each of the related arbitrations; secondly, the arbitrator failed to disclose two previous appointments in unrelated arbitrations by the claimant’s counsel; and thirdly, the claimant was a former client of the arbitrator.

The Board noted, regarding the first ground, that the related arbitrations were effectively one dispute and that they all still were pending. In the view of the Board, the mere fact of an arbitrator’s multiple appointments in parallel and related arbitrations under the same contract and between the same parties does not per se raise doubts regarding the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence.

Further, the Board concluded that the second ground was not a sufficient ground for releasing the arbitrator given the limited number of previous appointments, their remoteness in time and the fact that the appointments were made by different offices of the claimant’s counsel’s law firm. Moreover, the arbitrator’s disclosure was made without undue delay bearing in mind the procedural situation of the case.

As for the third ground, the Board noted that the arbitrator’s client-attorney relationship with the claimant concerned an unrelated project and was terminated far beyond the three-year period in the §3.1.1 of the Orange List of the IBA Guidelines 2014,51 which is, as a general rule, taken into account as part of the assessment in the SCC’s practice.

Case 10 (challenge dismissed)52

The respondents challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the claimant, asserting that the arbitrator’s law firm represented and continued to represent companies in a group of companies which had an interest in the outcome of the present dispute. The respondents further argued that the arbitrator had made inconsistent disclosures, and that the arbitrator’s law firm advised another party in a transaction involving the group and issued a press release which allegedly indicated that it advised on various projects involving the group.

The Board accepted that the parties’ submissions indicated that the group could be affected by as well as might have an interest in the outcome of the present arbitration. However, the group was not a current client of the arbitrator’s law firm and only received advice from the arbitrator’s law firm on a minor corporate matter closed two years prior. The other circumstances raised by the respondents did not detract from this. Moreover, contrary to the respondents’ allegations, the arbitrator’s disclosures were considered consistent.

The Board dismissed the challenge, emphasising that its decision was based on the current situation where the arbitrator’s law firm did not have an ongoing client engagement with the third-party group, and the arbitrator had a continuing obligation of disclosure should the situation change.

Case 11 (challenge dismissed)53

The respondent challenged the chairperson. The circumstance invoked by the respondent was that the chairperson had been appointed as the opposing party’s arbitrator in a dispute in a related matter, to which the respondent was a party. The claimant submitted that a challenge based on this circumstance was time-barred under the SCC Arbitration Rules.

The Board dismissed the challenge noting that even in the absence of being time-barred, the circumstance invoked would not lead to justifiable doubts as to the chairperson’s impartiality or independence. In particular, the Board found that the issues as well as the subject matters in the two arbitrations were insufficiently related.

Case 12 (challenge dismissed)54

The respondents challenged the sole arbitrator. The respondents invoked firstly, that the arbitrator had previously worked and continued to work with the claimant’s counsel and another person at the same arbitration institute, and secondly, that because of alleged undue influence and fraudulent activities on the part of the claimant’s sole owner, a new arbitrator should be appointed who was not a national of certain countries.

The Board dismissed the challenge, noting that the affiliation with the claimant’s counsel and the arbitration institute did not give rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence. Further, the Board noted that these circumstances fall under the §4.3.1 of the Green List of the IBA Guidelines 2014.55 As for the respondent’s second argument, the Board found that the respondent had not substantiated how the nationality of the arbitrator might affect the impartiality or independence of the arbitrator.

Case 13 (challenge dismissed)56

The claimant challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the respondent, citing concerns over impartiality and independence due to arbitrator’s prior employment at one of the law firms representing the respondent in the proceedings.

The Board dismissed the challenge, noting that the arbitrator had left the law firm in question over four and a half years earlier after a brief tenure. It further found that the arbitrator had minimal to no contact with the respondent’s counsel during the arbitrator’s tenure in the law firm. As a result, the Board concluded that the prior employment did not create justifiable doubts about the arbitrator’s impartiality.

Case 14 (challenge dismissed)57

The claimant challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the respondent, arguing that there were justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality. With reference to a disclosure made by the arbitrator, the claimant asserted that the arbitrator’s disclosure indicated the respondent had previously appointed the arbitrator numerous times, the arbitrator previously worked at the predecessor law firm of the law firm which represented the respondent, and the respondent’s counsel had appointed the arbitrator five times in a period of 10 years.

The Board dismissed the challenge, noting that the arbitrator and the respondent had clarified that the respondent had never previously appointed the arbitrator, and that no contrary evidence had been provided to the Board. The Board further noted that although the arbitrator’s former law firm appeared to have some connection with the law firm which represented the respondent, this connection was over four decades old. Additionally, as only one of the five prior appointments by respondent’s counsel occurred within the past three years, the situation did not fall under §3.1.3 of the Orange List of the IBA Guidelines 2014.58

Case 15 (first challenge dismissed, second challenge sustained)59

This case involved two challenges against the same arbitrator, the co-arbitrator appointed by the claimant. The first challenge was dismissed but the second challenge was successful.

The respondent first challenged the arbitrator on the basis that the arbitrator had been appointed by the claimant in a previous arbitration between the same parties, which concluded with a final award that was rendered two years prior. The Board found that the previous appointment did not per se constitute disqualification, especially given that the current arbitration relates to new circumstances and was different from the dispute settled in the previous arbitration between the parties. The Board dismissed this challenge.

A few months later, the respondent challenged the same arbitrator again. By this juncture, the claimant had submitted its statement of claim and related evidence. The respondent argued that these developments required the arbitrator to decide a specific issue which the arbitrator already had formed an opinion on in the previous arbitration between the parties (namely, when and how a time period specified in the contract expired).

The Board sustained the challenge in light of the new circumstances, noting that it had emerged that the present arbitration and the previous arbitration concern partly overlapping issues, and that the arbitrator was part of an Arbitral Tribunal which had taken a position in an award on a specific issue that would have been examined in the proceedings.

Case 16 (challenge sustained)60

The respondent challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the claimant based on the arbitrator’s disclosure that the arbitrator was, at the time, counsel to an entity whose board of directors was chaired by a board member of one of the claimants. Both the timeliness and the merits of the challenge were contested.

The Board first found that the challenge was timely, being submitted within 15 days from the arbitrator’s disclosures. In the view of the Board, the arbitrator’s disclosure obligation implies that the arbitrator conducted the necessary research to ensure that his or her disclosure is exhausting and complete. From that perspective, the arbitrator has a wider responsibility for research than the challenging party. Therefore, a party’s challenge should generally be seen as timely if it is triggered by the arbitrator’s disclosure and is submitted within the 15-day term established by the SCC Arbitration Rules.

In evaluating the merits, the Board noted that attorneys may have multiple assignments (including as board member at different companies), and this alone does not normally constitute sufficient ground for a challenge. However, this may change if the position as board member has a connection to the dispute being arbitrated, such as in the case in question, where the arbitrator had to assess the actions of a particular board member while simultaneously receiving instructions and remuneration from an entity whose board is chaired by that board member. Although the other matter was unrelated to the current arbitration, it had significant financial relevance to the arbitrator’s law firm and concerned a long-term client-attorney relationship. Moreover, the director in question was copied on client-attorney correspondence with the arbitrator. The Board sustained the challenge.

Case 17 (challenge sustained)61

The respondents challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the claimant on the grounds that the arbitrator was previously a partner at the claimant’s counsel’s law firm for several years. Since leaving that law firm, the arbitrator continued to work with lawyers from that law firm on unrelated matters for the past three years. One such matter was still ongoing where the arbitrator issued invoices to the client through that law firm.

The Board recognised that where a relationship between the arbitrator and a party or counsel ended more than three years before the start of the arbitration, it typically does not give rise to justifiable doubts regarding the arbitrator’s impartiality. However, in this case, the disclosed facts clearly showed that a working relationship between the arbitrator and the law firm had continued after the arbitrator’s departure. Therefore, the Board considered that the arbitrator was associated with the claimant’s counsel’s law firm in such a way that, a reasonable third person would have justifiable doubts concerning the impartiality and independence of the arbitrator. The Board sustained the challenge.

Case 18 (challenge sustained)62

The respondent challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the claimant as the arbitrator was approached in relation to the present arbitral appointment while working at a law firm which had, in the past three years, acted for an affiliate of one of the parties.

The Board held that the fact that the arbitrator had left the law firm by the time of the appointment did not automatically cure the conflict of interest arising out of the previous affiliation, especially since the appointment was made within a few days after the arbitrator’s departure from the law firm. The Board sustained the challenge.

Case 19 (challenge sustained)63

The respondent challenged the chairperson due to the connections between the chairperson and one of the claimant’s experts. In particular, the chairperson represented a party in an unrelated arbitration wherein the co-party to the chairperson’s client had called the same expert.

The Board sustained the challenge, noting that the chairperson would have regular professional contacts with the expert and rely on the expert’s testimony in the other matter. At the same time, the chairperson would have to evaluate the testimony of the expert in deciding on important issues of law in the present matter. The Board sustained the challenge and held that the continuous cooperation between the chairperson and the expert (albeit in another matter), may from the parties’ perspective, constitute an opportunity for undue influence or unconscious bias.

Case 20 (challenge sustained)64

The claimant challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the respondent on the basis that the respondent’s company representative and liquidator was the alternative board member of the arbitrator’s law firm (in which the arbitrator was the sole board member).

The Board sustained the challenge, noting that this relationship leads to objective doubts about the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence.

Case 21 (challenge sustained)65

The claimant challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the respondent. The challenge was based on the fact that the arbitrator and their law firm had provided legal services to affiliates of the respondent and on the timing of disclosures on these legal services, in particular: (1) the arbitrator was personally involved in representing an affiliate of the respondent in another arbitration during the present arbitration; (2) the arbitrator failed to fully disclose this information in a timely manner; (3) the arbitrator’s law firm had provided legal services in three other unrelated projects, which resulted in the law firm earning approximately EUR 425,000. This was only disclosed by the arbitrator in response to the respondent’s challenge; and (4) the arbitrator failed to disclose the circumstances in point 3 above in a timely manner.

The respondent disputed the challenge and claimed that no circumstances existed which, from an objective standpoint, could be viewed as a basis giving rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence. The respondent submitted several circumstances and arguments in support of its view.

First, the Board found the challenge to be timely. Second, the Board noted that the circumstances concerning the arbitrator’s recent involvement in representing an affiliate of the respondent often can lead to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence. The Board found the fees resulting from the arbitrator’s representation of the respondent’s affiliate not to be a large amount compared to the law firm’s overall revenue, but not insignificant either. The Board therefore concluded that the arbitrator’s involvement in another arbitration was sufficient to cast justifiable doubts on his impartiality or independence in the present arbitration. While the circumstances in point 3 above did not lead to justifiable doubts per se, the Board considered them as circumstances adding to those justifiable doubts. The Board sustained the challenge.

Case 22 (challenge sustained)66

The respondent challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the claimant on the basis that the arbitrator had a long-standing affiliation with a law firm which had been retained by the ultimate owner of one of the claimants (the “Owner”) on multiple occasions. The claimants contested both the timeliness and the merits of the challenge.

Regarding the issue of timeliness, the respondent had received the claimant’s request for arbitration identifying the respondent’s nominated arbitrator more than 15 days before raising its challenge. However, it was not clear to the Board whether the respondents had knowledge of all the relevant circumstances at that time. In particular, the arbitrator’s CV was not attached to the request and was only made available to the respondents on the SCC Platform at a later date. The Board found that it could not be established that the respondents had knowledge of all relevant circumstances prior to having access to the SCC Platform, and the challenge was timely when calculated from this date.

The Board sustained the challenge and considered the following facts particularly relevant to its assessment. The Owner was affiliated with one of the claimants. The arbitrator and the general counsel of the Owner were members of the same practice group at the arbitrator’s previous law firm, where the arbitrator worked for several decades. That law firm was not involved in the current dispute but continued to act for the Owner in other matters. Less than two years had passed since the arbitrator left that law firm, and the arbitrator continued to act as co-counsel with lawyers from that law firm even after the arbitrator’s departure.

Relationships between the arbitrator and the challenging party or their counsel etc.

Case 23 (challenge dismissed)67

The claimant challenged the chairperson based on an alleged heated argument between the claimant’s counsel and the arbitrator two years prior, when the arbitrator cross-examined the claimant’s counsel who had been called as a witness in a previous arbitration.

However, the Board was not persuaded that the arbitrator’s actions during the cross-examination were caused by personal reasons or outside the scope of assignment as counsel at the time. Further, there was nothing to demonstrate that there was any quarrel or exchange of views beyond what might normally occur during a cross-examination. The Board dismissed the challenge.

Case 24 (challenge dismissed)68

The respondent challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the claimant based on the arbitrator’s alleged connection to a third-party company (the “Company”) which was the counterparty in hostile settlement negotiations involving the respondent’s affiliate. According to the respondent, the arbitrator was connected to the Company as: (1) one of the partners in the arbitrator’s law firm used to work as the chief legal counsel of the Company and participated in the hostile settlement negotiations; and (2) the arbitrator’s spouse also represented the Company in those negotiations.

The Board dismissed the challenge noting that none of the parties to the settlement negotiations or the lawyers who represented them were a party to the arbitration or otherwise involved in the dispute. The settlement negotiations were also unconnected to the dispute at hand.

Case 25 (two challenges, both dismissed)69

This case involved two challenges against the co-arbitrator appointed by the claimant.

In the first challenge, the respondent raised three arguments. Firstly, the arbitrator had previously worked at the same law firm as the respondent’s counsel, shortly before the respondent’s counsel left to establish a competing law firm. Although the respondent’s counsel had left the law firm two months prior to the arbitrator’s appointment in the arbitration, the respondent argued that one should not delineate between calendar months when interpreting the phrase “within the past three years” in the IBA Guidelines. Secondly, the arbitrator and the respondent’s counsel were opposing counsels in another ongoing arbitration. Thirdly, the arbitrator’s law firm had been advising the claimant’s corporate group.

The Board dismissed the challenge. Regarding the first ground, the Board found that the situation fell outside the three-year time limit under the IBA Guidelines, and thus, the arbitrator was not obliged to disclose this circumstance. Moreover, the arbitrator and the respondent’s counsel were based in offices located in different countries. Regarding the second ground, the Board rejected the respondent’s contention that the matters at issue in the two arbitrations were so related as to give rise to a conflict of interest, noting that possible overlaps in legal questions do not lead to the assumption that the matters are related. As for the third ground, the Board held that that although the arbitrator’s law firm did advise the claimant’s creditor on a narrow issue, the law firm had no lawyer-client relationship with the claimant. Furthermore, the arbitrator had not been involved in advising the claimant’s creditor.

In the second challenge, the respondent requested that the Board reconsider its decision after introducing new evidence. This time, the respondent based the challenge on the engagement of the arbitrator’s law firm in another case, in which the firm had advised a third party regarding the restructuring of the claimant.

The Board dismissed the challenge, noting that the circumstances invoked were known to the respondent more than 15 days before submitting the challenge, which meant that the challenge was dismissed as time-barred under Article 19(3) of the SCC Arbitration Rules.

Case 26 (challenge dismissed)70

Following the rendering of the final award, the claimant appointed external counsel and submitted a challenge against the sole arbitrator together with a request for an additional award under Article 48 of the SCC Rules. In support of the challenge, the claimant argued that the arbitrator had previously been involved as counsel in various proceedings against direct and indirect shareholders of the claimant.

The Board found the challenge to the arbitrator to be inadmissible as the proceedings in the present arbitration had already been concluded and it had not yet been decided whether or not an additional award under Article 48 would be rendered. The challenge to the arbitrator was therefore dismissed without prejudice.

The Board reasoned that it follows from the Swedish Arbitration Act (see Section 27, para. 4), that the rendering of the final award concludes the arbitration proceedings. This is also evident from Article 49(2) of the SCC Rules, pursuant to which the SCC Board shall finally determine the costs of the arbitration before the Arbitral Tribunal renders the final award. Further, the Board noted that there is a possibility for a party to request an additional award under Article 48 of the SCC Rules, after the rendering of the final award. The request may be granted by the Arbitral Tribunal if the request is considered justified. In the present case, the final award had been rendered and there was no decision on any potential additional award.

Case 27 (challenge dismissed)71

The respondent challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the claimant on the basis that the respondent’s counsel was involved in an ongoing challenge to an arbitral award that was rendered in a previous arbitration by a tribunal which included the arbitrator. The respondent further alleged that the previous arbitration had been characterised by a hostile atmosphere and the serious criticism the respondent’s counsel had made against the arbitrator. The respondent further stated that if the challenged award were to be set aside by the Svea court of Appeal, the respondent’s counsel may be instructed to bring a liability claim against the arbitrator.

The Board dismissed the challenge, noting that the fact that an award had been challenged did not mean that the arbitrator should be disqualified in other cases with other parties involving the counsel who had challenged an award in an unrelated case. The Board pointed out that an attorney who initiates legal proceedings and/or criticises an arbitrator does so on behalf of their client. Furthermore, the Board emphasised that the right to choose and appoint arbitrators is a fundamental part of arbitration and of the claimant’s procedural rights. For these reasons, the Board held that the allegations made by the respondent did not demonstrate the existence of any justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence towards the parties.

Challenges based on the arbitrator’s conduct during the arbitral proceedings

The next most cited ground for challenge focused on decisions made by the arbitrator during the course of the arbitral proceedings which allegedly gave rise to justifiable doubts regarding the impartiality and independence of the arbitrator.

Case 28 (two challenges, both dismissed)72

The claimant challenged the entire Arbitral Tribunal consisting of three arbitrators on two separate occasions.

In the first challenge, the claimant argued that the Arbitral Tribunal had violated, amongst others, the European Convention of Human Rights by dismissing the claimant’s requests to submit additional submissions and postpone the main hearing, as the claimant’s newly appointed counsel was unavailable on the original hearing date.

The Board dismissed the first challenge for being out of time, as it was filed more than 15 days from the date of the Arbitral Tribunal’s procedural decision on these issues. The claimant’s subsequent requests for the Arbitral Tribunal to reconsider its decision did not affect this timeline. In any case, the Arbitral Tribunal is empowered to conduct the arbitration in such manner as it considers appropriate under Article 23(1) of the SCC Arbitration Rules, and the parties had agreed to the original hearing date.

Thereafter, the claimant brought a second challenge against the entire Arbitral Tribunal on the same grounds, with the additional argument that the Arbitral Tribunal was now the claimant’s counterparty in court proceedings that the claimant had commenced against the Arbitral Tribunal for its alleged breach of fundamental procedural principles.

The second challenge was once again dismissed by the Board, which found that the claimant’s filing of the lawsuit during the proceedings was a circumstance initiated by the claimant and beyond the control of the Arbitral Tribunal. In the view of the Board, the new circumstances did not lead to a different assessment than the decision which the Board previously made.

Case 29 (two challenges, both dismissed)73

The claimant challenged the sole arbitrator twice. Firstly, the claimant challenged the arbitrator on the basis that the case had been handled inadequately due to the sole arbitrator’s alleged incompetence and negligence. The allegations primarily related to a case management conference and included allegations that the arbitrator had circulated the meeting minutes late, made errors in the meeting minutes, and privately met with the respondent.

The Board dismissed the challenge, noting that there was no time limit for the circulation of the of the minutes in the SCC Arbitration Rules, and that nothing indicated that the meeting minutes were inaccurate. Moreover, there was no evidence that the arbitrator met privately with the respondent.

Secondly, about a month later, the claimant challenged the arbitrator again. The claimant referred to the same circumstances as before, as well as to two new facts: Firstly, an associate lawyer from the arbitrator’s law firm was appointed as an administrative secretary without the parties’ consent and attended a case management conference; and secondly, the revised timetable allegedly gave undue advantage to the respondent.

The Board declined to re-examine the facts which the claimant relied on in support of its earlier challenge. As for the new circumstances, the Board noted that the associate lawyer was not actually appointed as an administrative secretary and that parties did not object to his attendance at the case management conference. Moreover, the deadlines did not entail any undue advantage or disadvantage for any party. The Board dismissed the challenge.

Case 30 (challenge dismissed)74

The claimant challenged the sole arbitrator on three grounds: Firstly, claiming that the arbitrator’s decision to grant the respondent’s request for security for costs was extraordinary and that no reasonable person would consider the reasons for the decision to be objective or impartial; secondly, the arbitrator was allegedly exposed to the respondent’s marketing efforts directed at law firms; and thirdly, various relations between the arbitrator and the arbitrator’s law firm on one hand, and the respondent and its affiliates on the other hand. For example, the arbitrator had previously contributed to an article published by the previous employer of the respondent’s affiliate, and the arbitrator had previously attended the same conferences as the respondent’s affiliate.

The Board found that the second and the third ground were time-barred as the challenge was submitted more than 15 days after the arbitrator was appointed and the CV and confirmation of acceptance were uploaded to the SCC Platform. In any case, these circumstances would not lead to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence, especially given that there was no evidence that the arbitrator had any present or past relationship with the respondent. With respect to the first ground, the Board found no support for the allegation and noted that this circumstance fell under the Green List of the IBA Guidelines. The Board dismissed the challenge in its entirety.

Case 31 (challenge dismissed)75

The respondent challenged the chairperson based on the assertion that the Arbitral Tribunal had shown a tendency to favour the first claimant in the arbitration. The respondent relied on several instances of alleged unfair treatment, which related to inquires made by the Arbitral Tribunal during the hearing and the Arbitral Tribunal’s difference in treatment of the parties when it came to admitting new documents to the hearing bundles.

The Board dismissed most of the circumstances as time-barred because they occurred during a hearing which took place more than 15 days before the challenge was filed. In any case, the Board accepted the Arbitral Tribunal’s explanations on the procedural background and reasons for its conduct during the hearing. In particular, the Arbitral Tribunal’s explanation that the difference in treatment of the parties was caused by a misunderstanding regarding the documents which the first claimant sought to adduce. The Board dismissed the challenge.

Case 32 (three challenges, all dismissed)76

The respondent challenged the sole arbitrator appointed by the Board three times.

In the first challenge, the respondent argued that the arbitrator’s subsequent appointment as a member of the Board rendered the arbitrator partial towards the SCC.

The Board dismissed the first challenge, noting that whether a decision made by an arbitrator in an SCC arbitration goes one way or the other is irrelevant to the SCC. The SCC has no interest in the outcome of the dispute and is neutral and independent towards the parties and the arbitrators in the proceedings administered. The Board emphasised that nowhere in the SCC Rules or in the SCC’s internal policies is there any requirement for a board member to disclose, let alone resign as arbitrator, in SCC cases due to later being appointed as a member of the Board. The Board pointed out, however, that members of the Board are required to abstain from voting and participating in decisions related to a case where the board member has been appointed as an arbitrator. As a board member, the arbitrator was not involved in the management of the case. Accordingly, the respondent had failed to demonstrate the existence of any justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence towards the parties.

In the second challenge, the respondent argued that it had not received the statement of claim, and that the arbitrator was biased in favour of the claimant, as the arbitrator had previously decided that the uploading of the statement of claim to the SCC Platform would replace the sending of the documents to the respondent by courier.

The Board dismissed the second challenge, noting that the claimant had sent hard copies of the statement of claim by courier to the respondent. The documents could not, however, be delivered due to the respondent’s refusal to accept the delivery.

In the third challenge, the respondent submitted that there was a close relationship between the claimant’s counsel and the arbitrator where they supported each other during the proceeding. In support of these allegations, the respondent stated that, two weeks before the time limit for the final award, the claimant had asked the arbitrator to request a further extension of time for rendering the final award. The respondent submitted that the arbitrator would not have remembered the approaching deadline to render the final award without the claimant reminding them. The respondent further alleged that the arbitrator and the claimant shared the common goal of creating a final award in favour of the claimant and that, if the arbitrator achieved this goal, they would be rewarded.

The Board dismissed the third challenge. The Board emphasised that the claimant’s reminder regarding the extension of the time limit for the rendering of the award did not call into question the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence and that it was rather common practice in arbitration for parties to raise procedural issues such as time limits in communications with arbitrators. Moreover, the Board noted that the request for an extension of time to render the final award was submitted within a week from the rendering of a procedural order and a week in advance of the previous deadline for the award. The Board reiterated that this was in no way unusual in arbitration practice. Regarding the alleged relationship between the claimant and the arbitrator, the Board noted that the respondent had not specified the nature of the alleged relationship nor submitted any proof, instead merely submitting that they were supporting each other. The respondent further did not provide any proof as to a reward for the arbitrator for issuing an award in favour of the claimant. Accordingly, the respondent had failed to demonstrate the existence of any justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence towards the parties.

Challenges based on alleged breaches of confidentiality / political statements

The impartiality or independence of certain arbitrators was challenged on several instances based on statements that allegedly breached confidentiality obligations, or on political statements and/or activities by the arbitrators or their law firms directed against one of the parties.

Case 33 (challenge dismissed)77

The respondent challenged the chairperson on two grounds. Firstly, the respondent raised concerns regarding the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence following a post on the arbitrator’s law firm’s website which stated that the law firm had “extensive experience” advising clients concerning the particular area of law which pertained to the arbitration. Secondly, the arbitrator allegedly breached their confidentiality obligation by disclosing information about the current arbitration in another proceeding. In particular, the arbitrator had disclosed details in his resume with reference to “another proceeding”.

The Board dismissed the challenge. On the first ground, the Board noted that the respondent did not refer to any specific matter or parallel dispute to support its challenge. Moreover, the marketing material was a normal part of the law firm’s business development activities. On the second ground, the Board noted that the arbitrator had not disclosed the names of the parties, case number, or forum of the arbitration. The reference to “another proceeding” revealed no more than that the respondent was a party to other proceedings.

Case 3478 and Case 3579 (two challenges, both dismissed)

Two challenges were brought by two different respondents in two related arbitrations involving the same claimant. The claimant appointed the same co-arbitrator in both arbitrations.

In both instances, the respondents challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the claimant and argued that both arbitration cases involved alleged actions by the Russian state. Against this backdrop, the respondents raised concerns regarding the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence on the basis that the arbitrator was associated with an initiative that had used hostile language towards Russia and had directly contributed to a fundraising event hosted by the arbitrator’s chambers to support those affected by the war in Ukraine.

The Board dismissed the challenge, noting that the arbitrator, a member of the chambers, had minimal involvement in the event in question. There was no evidence of any direct or indirect statements made by the arbitrator regarding Russia. It also emphasised that, under the IBA Guidelines, a barrister’s chambers should not automatically be equated with a law firm in conflict assessments.80 In any case, even if the arbitrator’s involvement were attributed to them, it would not justify the challenge.

Case 36 (challenge sustained)81

The respondent challenged the chairperson, citing concerns regarding the arbitrator’s impartiality following a number of public statements made by the arbitrator which the respondent found to indicate bias against the respondent’s home state.

The Board noted that the arbitrator’s statements did not concern the respondent specifically and were made outside the context of any proceedings (including the present arbitration). However, the arbitrator’s statements were nonetheless critical of certain policies of the respondent’s home state in relation to Ukraine. As the respondent was a Russian entity subject to Ukraine-related sanctions, the Board found that the arbitrator’s statements may give rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality from the perspective of a reasonable third person. The Board sustained the challenge.

Case 37 (challenge sustained)82

The claimant challenged the chairperson based on a number of statements made by the arbitrator, which the claimant claimed to be biased and expressing a negative attitude towards the nationality of the claimant and its home state. Neither party was subject to Ukraine-related sanctions.

The Board emphasised that arbitrators, as a matter of principle, are entitled to have their own political opinions. An arbitrator’s expression of views concerning the actions of a government or a broader conflict generally will not give rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality as concerns nationals of a State involved or a private matter in dispute. However, the arbitrator had made statements which addressed more than the actions of the Russian government. Amongst other things, the arbitrator had made certain statements regarding in support of sanctions against Russian persons. This was relevant to the dispute as the respondent had cited sanctions as a reason for its non-payment under the underlying agreement.

The Board sustained the challenge finding that these circumstances gave rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality and independence.

Challenges based on the arbitrator’s nationality / qualifications

Lastly, some challenges were based on the arbitrator’s alleged connections with the nationality of one of the parties, or alleged lack of qualifications.

Case 38 (two challenges, both dismissed)83

This case involved two challenges against the chairpersons – one against the first chairperson, and one against the chairperson who replaced the first chairperson.

Firstly, the respondents challenged the first chairperson on the basis that the chairperson had robust ties with the claimant’s home jurisdiction (despite not sharing the same nationality as the claimant) and that the requirements for the chairperson requested by the respondents in the course of the arbitration were ignored.

The Board dismissed the challenge, noting that the chairperson was not a national of either parties’ home jurisdiction and thus, the chairperson’s appointment complied with Article 17(6) of the SCC Arbitration Rules.84 In this regard, an arbitrator’s professional experience in a particular area of law, legal writing and teaching, and/or past employments in the country of one of the parties, do not per se raise doubts in the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence. Moreover, the parties had not agreed on any specific qualifications of the chairperson and the circumstances invoked by the respondents did not directly or indirectly involve the parties or the subject matter of the dispute.

The first chairperson subsequently resigned for reasons unrelated to the challenge and a new chairperson was appointed.

Secondly, the respondents challenged the second chairperson on the basis that the new chairperson lacked experience in the law governing the merits and had close ties with the country in which the claimant is a national.

The Board dismissed also this challenge. Contrary to the respondents’ suggestions, the parties had not agreed on any qualifications of the arbitrators in the arbitration agreement. Like the first chairperson, the second chairperson was not a national of either of the parties’ home jurisdictions. The chairperson’s law firm’s experience involving parties from a certain geographic region does not per se raise doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence.

Case 39 (challenge dismissed)85

The claimant challenged the co-arbitrator appointed by the respondent, alleging insufficient French proficiency for conducting the proceedings. The claimant argued that this created a de jure or de facto impossibility for the arbitrator to perform duties, raising doubts about impartiality and independence. Additionally, the claimant asserted that the parties had agreed Arbitral Tribunal members would be proficient in French, which the arbitrator allegedly did not meet. The respondent disputed both claims, denying any agreement on language proficiency and arguing that the arbitrator’s French skills did not prevent effective performance. The respondent also contended that the challenge was time-barred.

The Board dismissed the challenge. The Board first noted that the challenge was not time-barred. It then noted that the threshold for removing an arbitrator due to inability to perform duties is high and found no justification for removal based on the arbitrator’s own statements on competency. Lastly, regarding the alleged language agreement, the Board found no evidence of an express commitment and emphasised that proving an unwritten agreement requires a high evidentiary standard.

Conclusions

This note has examined the legal standard and procedural aspects of challenges against arbitrators handled by the SCC and has summarised all the substantive decisions rendered by the Board between January 2020 and December 2024. From these decisions, some general guidelines and tendencies can be discerned.

In each challenge, the Board considers the applicable law, the applicable arbitral rules, and the best practices in international arbitration, including the IBA Guidelines.

The timeliness of the challenge was an issue in several challenges raised in the relevant time period. In such scenarios, the Board will carefully assess the facts to determine when the challenging party had knowledge of all relevant circumstances giving rise to the challenge. The Board has recognised the exacting nature of an arbitrator’s disclosure obligation, which imposes a wider responsibility for research than the challenging party. As such, where a party’s challenge is triggered by the arbitrator’s disclosure, it would generally be seen as timely if it is submitted within 15 days of the disclosure in question.

As to the substantive grounds for challenge, the majority of challenges between 2020 and 2024 were founded on the basis that “circumstances exist that give rise to justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality or independence”.

In assessing whether the standard of “justifiable doubts” under the SCC Rules is met, the Board has consistently applied an objective test, meaning that it is not the actual bias of the arbitrator, but the appearance of bias, which may trigger the dismissal of an arbitrator.

In deciding on a challenge, the Board has also undertaken an overall assessment of all relevant circumstances. This means that even if individual circumstances assessed separately are not sufficient to cast doubt on the challenged arbitrator’s impartiality or independence, a sufficient number of such circumstances assessed together may potentially lead to a different assessment.

Of the challenge decisions reviewed, the majority involved allegations of bias arising from relationships between the arbitrator and the counterparty to the challenge or their counsel.

(a) Where it was alleged that the arbitrator or their law firm had an attorney-client

relationship with the counterparty or its affiliates, the Board examined the nature and

frequency of those relationships. Key considerations included whether the engagement

was ongoing at the time of the challenge and whether the fees earned for such services

were significant.

(b) Where it was alleged that the arbitrator had a prior or ongoing working relationship

with the counterparty’s counsel, the Board carefully assessed the existence and extent of

any overlap. Consistent with the IBA Guidelines, relationships that ended more than three

years before the commencement of the arbitration would generally not give rise to

justifiable doubts as to the arbitrator’s impartiality. However, the Board carefully considers

whether the relationship may have continued beyond that period.

(c) Where it was alleged that the arbitrator had been previously appointed by one of the

parties or their counsel, the Board typically considered the frequency and remoteness of

the prior appointments, and whether there was any overlap in the disputed issues in

different arbitrations.

Several challenges involved the opposite scenario, where the arbitrator was alleged to be biased against the challenging party due to hostile or adverse relationships with that party or their counsel. In such cases, the Board’s primary consideration was whether these circumstances were related to the dispute at hand.

The second most frequently invoked basis for challenge concerned the Arbitral Tribunal’s procedural decisions and handling of the arbitration proceedings. None of these challenges were successful. When faced with such challenges, the Board generally gave weight to the Arbitral Tribunal’s justifications for its conduct, bearing in mind that the Arbitral Tribunal is empowered to conduct the arbitration in such manner as it considers appropriate under Article 23(1) of the SCC Arbitration Rules. The same principle applies under Article 24(1) of the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules.