Settlements in cases administered under the SCC Rules

Authors: Jake Lowther, Raoul J. Sievers, Joakim Raivio1

Table of contents

Introduction

Arbitral proceedings seated in Sweden are subject to the Swedish Arbitration Act (“Act”). Section 1 of the Act sets forth the arbitrability of the subject matter of a dispute. According to the Act, the subject matter will be arbitrable where the dispute concerns “matters in respect of which the parties may reach a settlement”.2 Settlement is therefore at the heart of arbitration in Sweden.3

Settlement offers parties an alternative pathway to conclude their disputes without the eventualities of a contested award. In recent years, the arbitrator’s possible role in facilitating settlement has come under renewed focus.4 To promote all available alternative methods of dispute resolution, the SCC has responded inter alia by updating the SCC Mediation Rules, and introducing a new tool, SCC Express. The SCC has also introduced new routines to promote the (parallel) use of mediation when it becomes aware of ongoing settlement discussions between the parties. This demonstrates the SCC’s continued commitment to providing parties with all tools to resolve their disputes in the most efficient way possible.

While there has been a growing emphasis on facilitating settlement in arbitration, 5 most national arbitration laws are silent on the acceptability of an arbitrator becoming involved in settlements (albeit a handful of national laws do promote early settlement6).

But what of the settlements themselves? In 2014, the SCC published a practice note on the costs of arbitration in settled cases.7 However, this 2025 report provides a deeper analysis of when the parties have reached a settlement in arbitrations administered under the SCC Rules. It examines patterns of settlements concluded in arbitrations administered under the SCC Rules over a three-year period, from 1 January 2021 to 31 December 2023. It also addresses some of the most pertinent questions regarding settlement in practice.

Is settlement more likely in domestic disputes? Which are the home jurisdictions of parties that settle the most cases? What relevance does the amount in dispute have for the likelihood of settlement? How much time does settlement actually save? Do bifurcation and partial awards accelerate settlement discussions? And at which stage of the proceedings are parties most likely to engage in successful settlement negotiations? Does the time of year make any difference?

The report examines the fundamental empirical questions surrounding settlement in practice. It analyses:

(i) the development of the number of settlements and their distribution across the different SCC Rules (section 3),

(ii) their geographical reach, industry, and contract type (section 4),

(iii) the relevance of the amount in dispute for the likelihood of settlement (section 5),

(iv) the average duration of settled cases and the time-savings achieved through

settlement (section 6),

(v) the effects of bifurcation and partial awards (section 7), and

(vi) the stages of the proceedings in which settlements most commonly occur (section 8).

By identifying both consistent patterns and notable variations in settlement behaviour, this report provides valuable empirical data that may assist practitioners in understanding the settlement dynamics in institutional arbitration. The findings herein contribute to the ongoing scholarly and professional discussion regarding the role of settlement within the broader framework of commercial dispute resolution mechanisms.

Methodology

Cases examined

The cases analysed for the purposes of this research were disputes that were administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules or the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules.

The present report examined all such cases in which the proceedings were not terminated with the rendering of an award on the merits. To this end, the research focused on matters which were concluded between 1 January 2021 and 31 December 2023. It thus also accounted for arbitrations which were initiated before 1 January 2021 as long as the date of the settlement fell within the defined time frame. Meanwhile, cases which were initiated in 2023 but only settled after 31 December 2023 are not reflected.

Confirmed and unconfirmed settlements

The report distinguishes between confirmed and unconfirmed settlements.

Confirmed settlements are cases in which the parties jointly made a declaration either to the SCC (before referral) or to the Arbitral Tribunal (after referral) that they reached an agreement on the asserted claims and wished to withdraw all claims. Where the case had already been referred to the Arbitral Tribunal, the parties’ agreement would often be recorded in a consent award. These cases are considered confirmed settlements.

Settlement rates

The report also examines settlement rates. To do so, the analysis compares the total number of cases initiated in a year and the number of these cases which were ultimately settled until the end of the period.

International and domestic disputes

In line with the SCC’s common practice, the report will distinguish between international and domestic disputes.

In this regard international cases are proceedings which involve at least one party that is not resident in Sweden, or, in case of a legal person, that is not registered in Sweden. In contrast, in domestic disputes all parties involved in the proceedings are either resident or registered at an address in Sweden.

Days until settlement

The report further examines the stage of the proceedings in which settlement occurred. To this end, the report first differentiates between two broad procedural stages, namely before referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal on the one hand and after such referral on the other

Before referral

Yet, the report acknowledges that, in particular with regard to settlements that occurred after referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal, this distinction in and of itself is too broad.

Therefore, the report further examines the last procedural milestone that was reached before the parties reached their agreement to settle. In this respect, before referral, the report distinguishes between settlement agreements that were concluded immediately after the request for arbitration was filed and those that were only registered after the answer to the request for arbitration was submitted.

In theory, the SCC’s decision on the amount of the advance on costs the parties shall pay constitutes another procedural milestone that might prompt the parties to reach a settlement. However, with only narrow exceptions,8 the SCC’s practice is to decide on the advance on costs directly upon receipt of the answer to the request for arbitration. This ensures an efficient and expeditious process. However, it is then difficult to separate the two procedural milestones. Consequently, this report only refers to two pre-referral milestones, the filing of the request for arbitration and prior to the filing of the answer to the request for arbitration, and the filing of the answer to the request for arbitration and prior to the referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal.

After referral

After referral, the present analysis first found that some settlements occurred before and promptly after referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal before any further procedural milestones were passed. The following sub-stages reflected in the present report display the last respective procedural milestone completed by the parties before settlement was reached and includes the case management conference, the first procedural order, the statement of claim, the conclusion of the first round of written submissions, the conclusion of the last round of written submissions, and the pre-hearing conference. Finally, the report examined whether there were instances where the parties only settled following the hearing on the merits or even after submitting their respective post-hearing briefs.

Stage of settlement

The report analyses the time passed until settlement. In this respect, the relevant timespan is measured as the number of days that have passed between the date on which the matter was registered by the SCC and the date on which the matter was marked as terminated.

To clarify, the date on which the matter was registered by the SCC may differ from the date of filing the request for arbitration, for example if filing takes place outside of business hours. However, it will be a date promptly after the request for arbitration was filed. For the same reason, the date on which the matter is marked by the SCC as terminated is a date promptly following a notice of the parties to the SCC to dismiss the case (before referral), or a notice to the attention of the SCC by the Arbitral Tribunal that the proceedings are terminated (after referral).

Subdivision in years

For the purposes of certain assessments, the report will subdivide the settlements in years to enable the tracking of distinct developments over the years. In this context, the respective years will be the years in which the settlement was recorded, i.e. the date on which the matter was marked as terminated following a circumstance which the SCC considers as a case of confirmed settlement.

Bifurcation

Finally, the report examines the role of bifurcations of the procedure in the context of subsequent settlements. These cases, per definitionem, are exclusively disputes were settlement occurred after referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal.

Cases that were considered bifurcated for the purposes of the report were such cases in which, by virtue of a procedural order or agreement by the parties, the parties’ submissions were first limited to a certain set of issues which were then finally decided by the Arbitral Tribunal. Here, the report distinguishes between bifurcations in favour of a separate determination of jurisdictional objections and those bifurcations which served the Arbitral Tribunal to separately assess a set of substantive issues.9

Total number of settlements in the examined time span under the SCC Rules

As a preliminary matter, the report assessed the development of the gross number of settlements across the examined time period.

Total number of confirmed and unconfirmed settlements

In the examined time, which spans between 1 January 2021 and 31 December 2023, the SCC registered the conclusion of 460 proceedings that were conducted either under the SCC Arbitration Rules or under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules. Of these 460 cases, 121 were terminated without a final decision on the merits of the case (26.3%).

As pointed out before, these 121 cases were subsequently subjected to a thorough analysis of the circumstances of their conclusion and, in particular whether the file contains a record of a settlement. This way, the report identified 74 confirmed settlements (61.2% of the terminated cases), including consent award.

Hence, more than one in six proceedings administered under the SCC Rules was terminated by virtue of a confirmed settlement. In another 47 cases, the reasons for the termination of proceedings prior to a ruling on the merits remained unknown. Accordingly, these are considered as unconfirmed settlements (38.8% of the terminated cases).

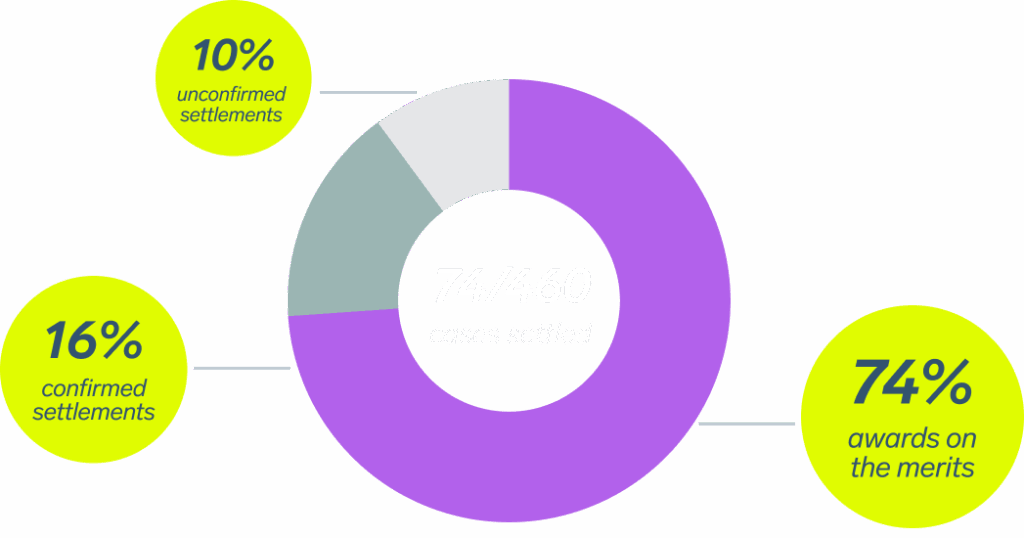

Figure 1: Distribution of awards on the merits and (un)confirmed settlements (2021-2023)

Yet, this means that out of the 460 cases, 16.1% were concluded through a confirmed settlement whereas such a settlement cannot be ruled out in another 10.2% of proceedings administered by the SCC in the analysed time span.

As mentioned before, to avoid distorting the findings of this report, the following analysis is confined to an assessment of the 16.1% of cases in which a settlement could be confirmed, unless expressly indicated otherwise.

More than every fifth case confirmed settled in 2022

In our analysis, we have also assessed the development of the number of settled cases over the years. The year-on-year number of settlements is then to be compared to the number of cases concluded in the respective year.

In this regard, we observed that the number of settlements first increased from 21 to 28 between 2021 and 2022, while proceedings terminated following a confirmed settlement slightly dropped to 25 in 2023. Putting these numbers in perspective: in 2021, a total of 160 cases were concluded under the SCC Rules (i.e. under the SCC Arbitration Rules and the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules), of which 21 cases are considered confirmed settlements (13.1%).

In the following year of 2022, the SCC saw only 146 cases concluded while registering 28 confirmed settlements (19.2%). In 2023, 154 proceedings under the SCC Rules were concluded, of which 25 were terminated following a settlement (16.2%).

It can be noted that 2022 was an exceptional year for settlements at the SCC, as a comparably low number of concluded proceedings coincided with a higher number of settlements. As a result, roughly every fifth case was settled in 2022.

Fewer settlements under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules

The caseload examination further distinguished between the applicable set of SCC Rules, namely between the SCC Arbitration Rules and the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules.

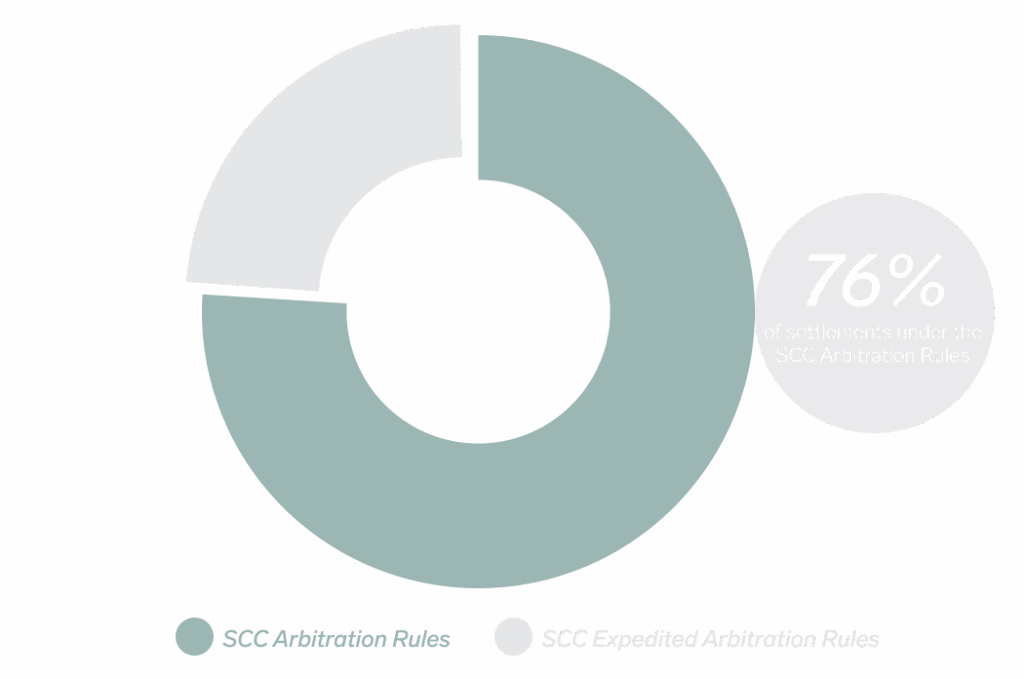

We note that out of the 74 confirmed settlements, 56 occurred in proceedings conducted under the Arbitration Rules (75.7%). These 56 confirmed settlements relate to the total number of 303 proceedings administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules which were concluded between 1 January 2021 and 31 December 2023. This equals a settlement rate of 18.5% of all arbitrations concluded under the SCC Arbitration Rules in the analysed time span.

Figure 2: Distribution of settlements between the SCC Arbitration Rules and the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules

Another 18 cases were terminated following a confirmed settlement in proceedings administered under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules (24.3% of all settlements in proceedings under the SCC Rules). These 18 confirmed settlements compare to a total of 157 proceedings under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules which were concluded in the same time span. This results in a rate of 11.5% of all proceedings conducted under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules being terminated following a confirmed settlement

The observed settlement rate is thus significantly higher in proceedings under the SCC Arbitration Rules (18.5%) compared to cases administered in accordance with the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules (11.5%).

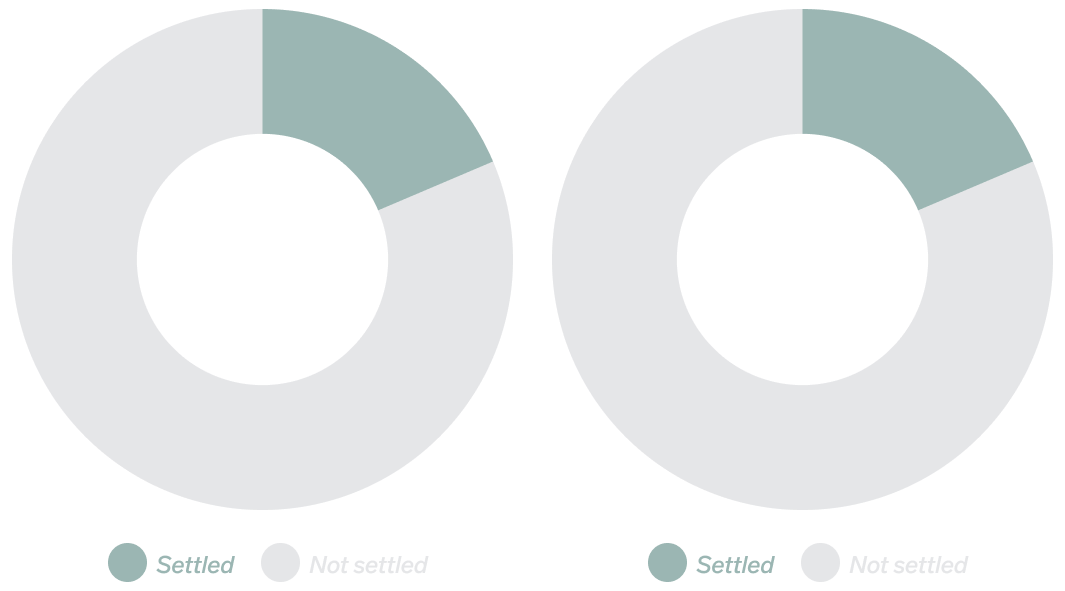

Figure 3: Distribution of settlements between the SCC Arbitration Rules and the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules

The number of arbitrators

According to our analysis of the 74 confirmed settled cases, the distribution of the number of arbitrators was as follows.

SCC Arbitration Rules: In 24 cases (65%), the Arbitral Tribunal was comprised of three arbitrators, 13 cases (35%) had a sole arbitrator. In the remaining 19 cases, the Arbitral Tribunal had not been appointed at the time of settlement.

SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules: Under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules, all cases are determined by a sole arbitrator. In 9 cases the parties settled following the appointment of the Arbitrator, and in the remaining 9 cases, no arbitrator had been appointed at time of settlement.

Overall, 32% of all settled cases had three arbitrators, 30% had a sole arbitrator, and in 38% of cases, settlement was reached before any arbitrator was appointed.

To put these figures in context, according to SCC statistics for 2024, In 2024, arbitrators were appointed in a total of 69 cases under the SCC Arbitration Rules. In 44 disputes (64%), the tribunal consisted of three arbitrators. In 25 disputes (36%), the Arbitral Tribunal consisted of a sole arbitrator.

This demonstrates that the distribution of the number of arbitrators in settled cases administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules closely reflects the SCC’s overall statistics. It further suggests that the number of arbitrators is not a factor influencing settlement.

Parties’ home jurisdictions and amounts in dispute

The analysis also assessed geographical and sectoral implications on the settlement rate, in particular:

(i) the distribution of settlements across domestic and international disputes (section 4.1),

(ii) the home jurisdictions of parties that settled their dispute (section 4.2), and

(iii) the industries and contract types involved (section 4.3).

Higher settlement rates in domestic disputes

As a preliminary matter, and as is customary in the SCC’s annual statistics, we have distinguished between “domestic” and “international” disputes. Cases involving Swedish parties only are classified as “domestic”. A dispute involving one or more parties from another country is classified as “international”. Where a dispute involves parties from outside Sweden but from the same jurisdiction, this is also classified as “international” in the SCC’s statistics.

From our analysis, we noted that 44 of the 74 settlements occurred in domestic disputes (59.5%). In contrast, only 30 settlements were related to international cases. This is remarkable insofar as it demonstrates what might be considered an overrepresentation of domestic cases in the settlement statistics compared to the overall distribution of cases registered with the SCC in the same timeframe. In fact, between 1 January 2021 and 31 December 2023, the SCC registered slightly more international cases than domestic cases (50.1% international cases).

This conforms to the trend of internationalisation of SCC cases. For example, in 2024, 65% were international of the cases that were administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules and 35% were domestic.

Many settlements among parties from the UK and the Nordics

We subsequently examined the most frequent home jurisdictions of the 102 parties that settled their disputes. Given the finding that a majority of the settlements occurred in domestic disputes, it should come as no surprise that most parties involved in confirmed settlements came from Sweden (57 parties, 55.9% of all parties). The most common home jurisdiction of parties involved in settlements were the United Kingdom (UK) (5.9%), Denmark (4.9%), Finland (4.9%), Germany (2.9%), Norway (2.9%), and Spain (2.9%). This distribution of home jurisdictions largely corresponds to the statistics on the jurisdictions most commonly represented in arbitrations administered by the SCC.

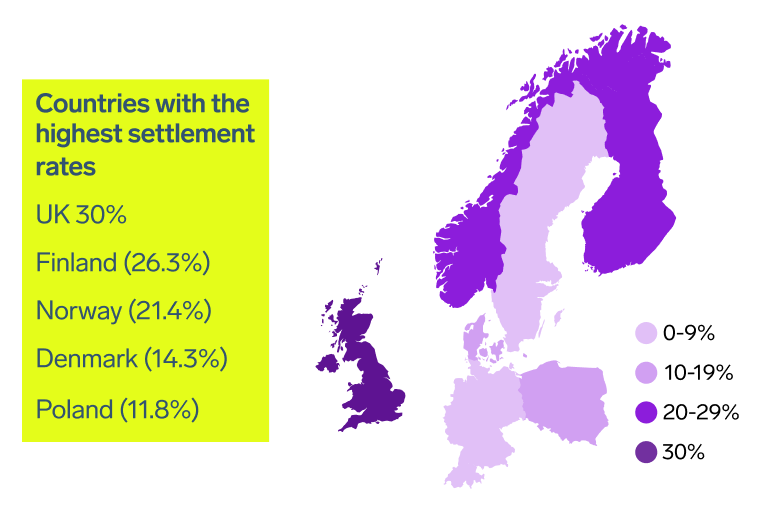

However, we then compared the number of parties from a jurisdiction that had settled their dispute to the overall number of parties from the same jurisdiction that registered10 a dispute with the SCC in the same time frame to obtain a settlement rate based on a party’s home jurisdiction. In order to maintain a reliable basis for the statistics, this assessment was limited to the ten most frequent home jurisdictions in the relevant time period.11

Here, parties from the UK achieved the highest settlement rate as six of 20 parties agreed on a settlement (30%). The UK is followed by Finland (26.3%), Norway (21.4%), Denmark (14.3%), and Poland (11.8%).

Among the ten most frequently represented home jurisdictions at the SCC, parties from the Russian Federation and from Ukraine were the least likely to settle their disputes. In fact, not one of the 39 Russian parties nor one of the 15 Ukrainian parties registered by the SCC in the relevant time span settled a dispute. Similarly, only one out of 25 US parties approved a settlement agreement (4%).

Figure 4: Settlement rates among the ten most frequently represented jurisdictions in SCC arbitrations

Notably, although domestic disputes displayed a comparably high settlement rate considering the ratio of cases registered by the SCC, Swedish parties are not among those with the highest settlement rate when their involvement in domestic and international disputes is considered (8.2%).

Prevailing industries and contract types

A review of the confirmed settled cases reveals that the most common industries represented among these cases were real estate and construction (20%), retail and consumer products (18%), and energy (15%). The leading contract types were share purchase agreements (28%), construction contracts (11%), and supply agreements (9%).

In comparison, the SCC’s statistics from 2024 reveal a similar distribution across industries and contract types.12 This indicates that the profile of settled cases largely reflects the overall SCC caseload, including the recent increase in corporate and post-M&A disputes.13 However, there is a higher number of settled cases originating from construction contracts in proportion to the SCC’s overall caseload.

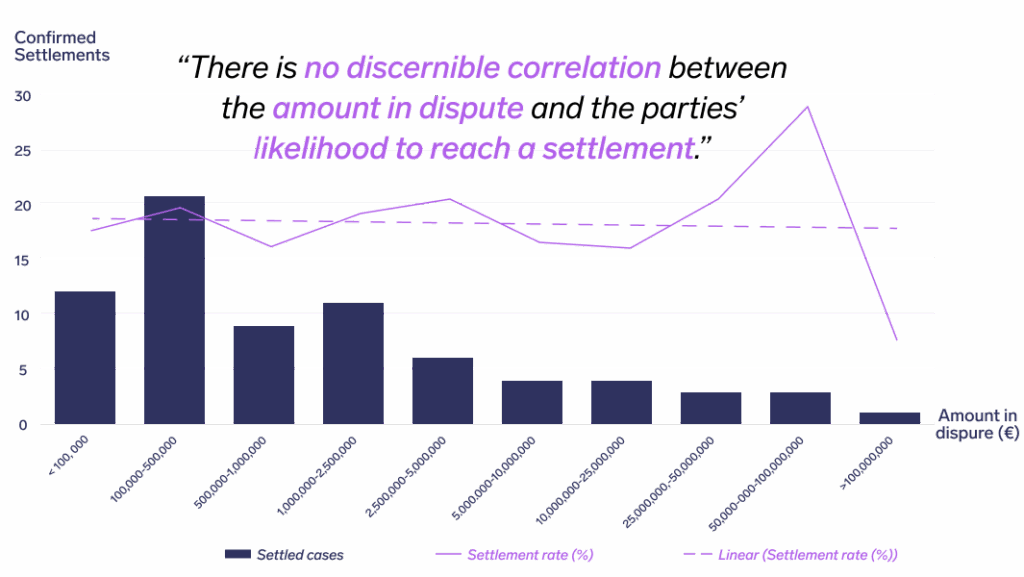

No relevance of amount in dispute

One further aspect of interest is the correlation between the amount in dispute and the frequency of settlements. In this regard, the disputed amounts were divided into ten brackets ranging from below EUR 100 000 to over EUR 100 000 000.

Remarkably, significantly more than half of the settlements occurred in cases in which the amount in dispute was under EUR 1 000 000. Out of the 74 confirmed settlements, 12 were registered in proceedings over disputed amounts below EUR 100 000 (16.2%). Another 21 confirmed settlements were agreed in disputes over an amount between EUR 100 000 and EUR 500 000 (28.4%). A further nine settled cases concerned a volume of claims between EUR 500 000 and EUR 1 000 000 (12.2%). Hence, arbitrations for amounts below EUR 1 000 000 accounted for 42 of the 74 confirmed settlements (56.8%).

In the region above EUR 1 000 000, disputes over amounts between EUR 1 000 000 and EUR 2 500 000 accounted for eleven settlements (14.9%) while the analysis identified six settlements in the following bracket between EUR 2 500 000 and EUR 5 000 000 (8.1%). Four settlements occurred in disputes over claims for 5 000 000 and 10 000 000 (5.4%) and disputes over EUR 10 000 000 to 25 000 000 (5.4%) respectively. Another three respective settlements were registered in cases for EUR 25 000 000 to 50 000 000 (4.1%) and cases for 50 000 000 to 100 000 000 (4.1%). Finally, the parties managed to settle a dispute over more than EUR 100 000 000 once (1.4%).

Figure 5: Number of settlements and settlement rates based on the amount in dispute

Accordingly, over half of all confirmed settlements in the analysed timespan concerned claims for less than EUR 1 000 000. Two thirds of all settlements related to disputes for amounts below EUR 2 500 000 (53 cases or 71.6% of all examined settlements). However, this distribution is largely reflective of the overall distribution of amounts in disputes in cases administered by the SCC. While the data show a marked increase and subsequent decrease in settlement rates in cases with the highest amounts in dispute, these fluctuations should be interpreted with caution. They are attributable to the limited number of cases in this category and do not necessarily indicate a broader trend. A comparison of settlement rates in the aforementioned brackets does not follow any discernible pattern.

Average duration of settled cases

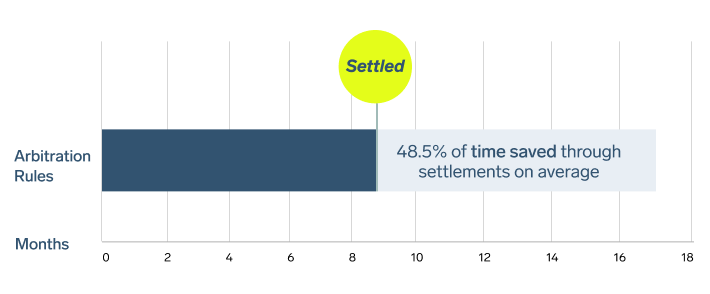

The analysis subsequently assessed the benefits of settlements with regard to the duration of the dispute resolution process. Overall, parties spent an average of 7.7 months in proceedings under the SCC Rules until they could find an agreement to settle. In fact, the median duration was only at 5.3 months. These results can further be subdivided into the durations for proceedings under the SCC Arbitration Rules and under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules.

Settlement halves the duration of the process under the SCC Arbitration Rules

Under the SCC Arbitration Rules, settlement occurred after an average of 8.8 months while the median duration of proceedings until the parties’ agreement to settle was at 6.4 months. For reference, the average duration of proceedings administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules which were concluded in the same time frame was at 17.1 months with a median of 12.4 months.

Figure 6: Average time saved through settlement of cases under SCC Arbitration Rules

Accordingly, by settling their dispute the parties cut their dispute resolution process short by an average of 8.3 months (48.5%) and a median of 6 months (48.4%) – effectively halving the duration of their dispute resolution process.

At the SCC, we know that for arbitration users, time is money. From the SCC’s Report on costs of arbitration and apportionment of costs under the SCC Rules, we know that the mean costs of legal representation are between 13.5 and 12.85 times the costs of arbitration, 14 i.e., the arbitrators’ fees, the SCC’s administrative fee, and any expenses. Given the general rule that the lengthier the proceeding, the greater the costs of legal representation, settlements represent an important method that is at the parties’ disposal to reduce the overall costs of dispute resolution

Parties are twice as fast to settle under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules

Under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules, parties reached a settlement after an average of 4.3 months and a median of 3.8 months. Thus, parties were twice as fast to find a settlement under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules compared to the SCC Arbitration Rules. To put these figures into context, 100% of arbitrations administered under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules in 2023 were concluded within six months of referral to the Arbitrator. As a result, parties also stand to save a significant amount of time by settling their cases under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules

Partial awards do not (significantly) accelerate settlement

Another point of interest of the present report was the role of bifurcation and its effects on settlements. There may be a conceptual expectation that bifurcation facilitates settlement as it provides the parties with a degree of certainty as to the prospects of success of (parts of) their case. In light of this, we examined the time span between a partial award and settlement.

Out of the 74 confirmed settlements, 6 originated from proceedings which had been bifurcated. In four of these disputes, the Arbitral Tribunal had bifurcated the arbitration to allow for dedicated submissions on jurisdictional objections, two more bifurcations sought a separate determination of substantive issues.

As one might imagine, these bifurcated cases were procedurally and substantively complex, featuring investment treaty arbitrations, insolvency and bankruptcy issues, counterclaims, and very often concerning large amounts in dispute.

Where proceedings were bifurcated, an average of 438 days (14.6 months) passed between the rendering of the partial award and the parties’ agreement to settle. Notably, the median was significantly lower at 217 days (7.2 months). In total, these six proceedings took an average of 29.8 months and a median of 18.5 months from registration of the case with the SCC to termination of the matter by settlement. On average, the partial award was hence rendered around the half-way mark between initiation of the arbitration and settlement.

Thus, the parties spent an almost equal amount of time after the rendering of a partial award in the arbitration as they had spent between registration of the case and the rendering of the partial award. In comparison to the overall duration of these bifurcated cases, the rendering of a partial award does not appear to have been a significant factor to promote the settlement of the dispute. In other words, while one might have expected the settlement occur relatively close in time to the rendering of the partial award, such a correlation is not reflected in the analysis. However, it should be noted there remains uncertainty as to the duration of the dispute had the parties not settled.

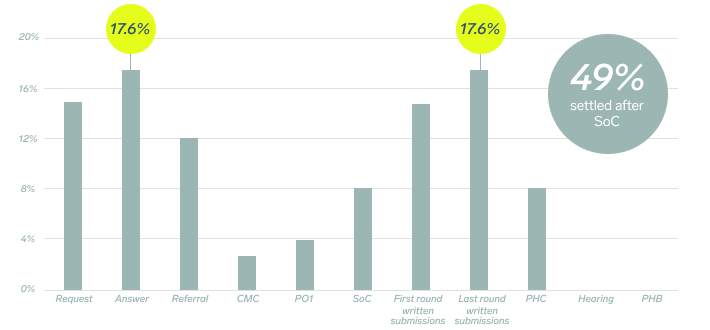

Stage of proceedings

At which stage of the proceeding is settlement most likely to occur? As mentioned before,15 the analysis first broadly distinguishes between settlements that occurred before and after referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal. We observed that 24 of the 74 settlements were confirmed already before the case was referred to the Arbitral Tribunal (32.4%). Accordingly, the remaining 50 settlements occurred after referral of the dispute (67.6%). Remarkably, roughly one third of all settlements were agreed already before the referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal.

More pre-referral settlements over the years

Before examining the specific stages of the procedure where settlement occurred, it is worth noting that, during the analysis of the stages of proceedings in which the settlements are recorded, we observed a shift in the distribution of pre- and post-referral settlements over the examined timespan.

Figure 7: Average distribution of pre- and post-referral settlements

In 2021, the first year under examination, 17 of 21 confirmed settlements occurred after the case was referred to the Arbitral Tribunal (81%) while only 4 disputes were settled before referral (19%). The share of pre-referral settlements already significantly increased in 2022 when 8 of 28 settlements were registered before the case was referred (28.6%) with nevertheless 20 settlements recorded after referral (71.4%). However, the distribution of pre and post-referral settlements flipped for 2023. In the last year considered for the purposes of the present report, 13 out of 25 settlements were recorded before the case was referred to the Arbitral Tribunal (52%). In that year, only a minority of 12 cases were settled post-referral (48%).

Specific stages of proceedings in which settlement occurs

The analysis subsequently took a closer look at the precise stages of the proceedings in which the parties agreed to settle. In line with the approach described above, the analysis will subsequently rely on the last procedural milestone reached by the parties before the proceedings were terminated.

Before referral

Regarding settlements that occurred before referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal, the present report considered whether or not the respondent had already submitted their answer to the request for arbitration. For the purposes of the present report, we considered two milestones:

(i) the filing of the request for arbitration and prior to the filing of the answer to the request for arbitration; and

(ii) the filing of the answer to the request for arbitration and prior to the referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal, which is approx. the same time as the SCC’s decision on the advance on costs the parties shall pay (see section 2.5.1).

Notably, 11 of the 24 settlements that were reached before referral were already agreed before the respondent even filed their answer (45.8% of all pre-referral settlements or 14.9% of all 74 confirmed settlements). Consequently, the remaining 13 settlements that occurred before the case was referred to the Arbitral Tribunal were registered in the period between the filing of the respondent’s answer to the request for arbitration and the referral of the case (54.2% or 17.6% of 74 confirmed settlements respectively).16 This stage includes the communication of the SCC’s decision on the advance on costs to be paid by the parties, which as mentioned above is in general made directly upon receipt of the answer. The decision is taken once all the claims, counterclaims, and set offs have been made, and where there are no procedural decisions such as to the applicable rules, the number of arbitrators, joinder, consolidation, etc. still outstanding. It is therefore difficult to separate the answer to the request for arbitration from the SCC’s decision on the advance on costs to determine which has influenced the parties’ settlement.

After referral

The period of an arbitral proceeding after referral offers a wide array of procedural stages to distinguish. For the purposes of the present report we examined:

(i) whether the parties and the Arbitral Tribunal had already conducted a case management conference,

(ii) whether the Arbitral Tribunal had issued the first procedural order,

(iii) whether the claimant had submitted their statement of claim,

(iv) whether the first round of written submissions had been concluded,

(v) whether the last round of written submissions had been concluded,

(vi) whether the parties and the Arbitral Tribunal had conducted the pre-hearing conference before the hearing on the merits,

(vii) whether the parties had concluded the hearing on the merits, and

(viii) whether the parties had submitted their respective post hearing briefs.

Figure 8: Distribution of settlements as per stage of proceedings

With the beginning of the written submissions, the numbers of settlements slowly start to pick up. In 6 cases, the parties agreed to settle after the claimant(s) had submitted their statement of claim (12% of all post-referral settlements or 8.1% of all settlements). Another 11 settlements were reached once the respondent(s) had filed their statement of defence and thereby concluded the first round of written submissions (22% or 14.9% respectively). The conclusion of the final round of written submissions ultimately inspired a further 13 settlements (26% or 17.6% respectively). Hence, at the time the parties convened for the pre-hearing conference, 91.9% of settlements had already occurred.

The remaining six settlements were reached once the parties had conducted the pre-hearing conference (12% of all post-referral settlements or 8.1% respectively). Notably, we observed no settlements once the parties had participated in the hearing on the merits. This suggests that the parties’ willingness to explore the prospects of settlement is lower if they have already committed a significant proportion of the financial resources the case necessitates, and they anticipate a binding adjudication of their dispute in the near future.

Settlement and arbitrator fees

As mentioned above, the SCC first considers the question of the costs of arbitration after the respondent has submitted its answer to the request for arbitration, and prior to the referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal. If the parties settle the case after it has been referred to the Arbitral Tribunal, what effect if any does this have on the arbitrator fees? As always, the answer is “it depends”.

The starting point in deciding the arbitrator fee in any arbitration at the SCC prior to the referral of the case is an independent assessment by the SCC of how much work the Arbitral Tribunal will likely need to do in the relevant case and in relation to what might be considered “normal” in a similar case.

In a case expected to involve work of a “normal” scope, the SCC will set the advance on costs for the chairperson (or the sole arbitrator) to the so-called “standard” of the SCC’s table of costs based on the value in dispute in the case (ad valorem).

Based on this table of costs, where the Arbitral Tribunal is expected to undertake more or less than the “normal” amount of work in a case, the SCC may decide to set the advance on costs to the “minimum” or “maximum” amounts. It may also set the advance on costs to an amount in between these values.17

When an arbitration terminates earlier than the deadline for the rendering of the final award, such as in the case of settlement, the SCC applies various routines when deciding the fees of the arbitrator(s), and how much of the advance on costs is to return to the parties. The SCC’s decision on the arbitrator fees largely follows from the stage of the proceedings at the time of the termination. All relevant circumstances of the individual case shall be taken into account, including the extent to which the Arbitral Tribunal has handled the case efficiently and expeditiously.

It will come as no surprise that the earlier the withdrawal or settlement takes place, the lower the percentage of the total estimated fee that the arbitrator will generally receive. However, where it has been appropriate for the arbitrator to draw the parties’ attention to the potential benefits of engaging in settlement discussions, and the parties have been able to settle, this may be taken into account when determining the arbitrator’s fees, as the arbitrator has been active in ensuring that the case is resolved efficiently. However, the SCC always undertakes a case-by-case assessment.18 Among the factors that the SCC takes into account when setting the fees include:

(i) whether the settlement is to be confirmed in an arbitral award;

(ii) the total time spent by the Arbitral Tribunal on the case;

(iii) the actual work of the Arbitral Tribunal (i.e., has the Arbitral Tribunal familiarised itself with the case prior to the hearing, which can be assumed to be the case if the settlement is reached mere days before the hearing date, or if the arbitrator has written the grounds for the award, etc.);

(iv) the extent to which the Arbitral Tribunal has handled the case efficiently and expeditiously; and

(v) the total time spent by the chairperson and the co-arbitrators respectively on the case.

Accordingly, the SCC has significant discretion to ensure that the arbitrator fees are appropriate taking into account all the circumstances of the case and the nature of the settlement.

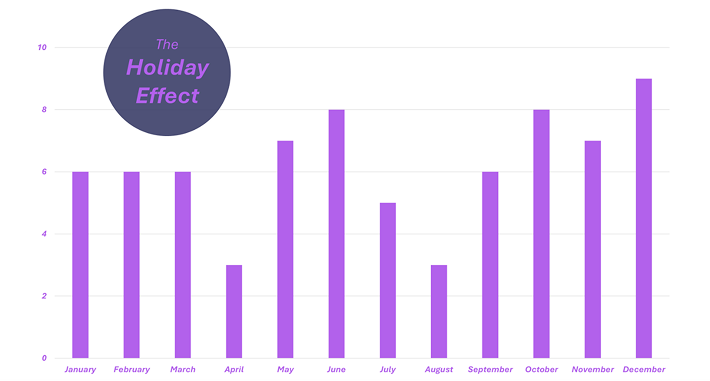

8.2.4. The holiday effect

When analysing the data, it emerges that the time of year may influence the likelihood of the parties to settle the arbitration. From our analysis of the number of settlements per month across the period, we note there appears to be an increase in the number of cases settling in two periods over the course of the calendar year.

As can be seen from the graph below, the number of settlements increases in the months immediately prior to the main holiday periods in Sweden, i.e., Swedish Midsummer, which falls on or near the date of the summer solstice in the Northern Hemisphere, and the end-of-year festive season. These increases are followed by relatively clear decreases.

Figure 9: Distribution of settlements per month

Accordingly, the time of year and specifically the proximity to certain Swedish holiday periods, appears to influence the likelihood of the parties to reach a settlement.

Summary and interpretation of results

Summary of results

The results of this report can be summarized in the following 15 findings:

- Significantly more cases were settled under the SCC Arbitration Rules than under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules.

- The distribution of the number of arbitrators in settled cases administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules closely reflects the SCC’s overall statistics and suggests that the number of arbitrators is not a factor influencing settlement.

- Settlements were registered more frequently in domestic disputes compared to international disputes.

- Parties from the UK and the Nordics are most likely to settle in arbitrations under the SCC Rules.

- The profile of settled cases largely reflects the overall SCC caseload, including the recent increase in corporate and post-M&A disputes.

- There is no discernible correlation between the amount in dispute and the likelihood of settlement.

- Settlement reduces the average duration of the dispute resolution process almost by half in proceedings under the SCC Arbitration Rules.

- Parties took twice as long to settle an arbitration under the SCC Arbitration Rules compared to the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules.

- Roughly a third of all settlements were registered even before the case was referred to the Arbitral Tribunal.

- Bifurcation and partial awards do not (significantly) accelerate settlement.

- The number of pre-referral settlements increased significantly over the examined period.

- Settlement rates rapidly increase following the parties’ initial and later exchanges of written submissions.

- Most settlements occur either immediately before referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal or right after the conclusion of the final round of written submissions.

- No settlements were registered once the parties had conducted the hearing on the merits.

- The time of the year, and specifically the proximity to holiday periods, appears to influence the likelihood of the parties to reach a settlement.

Interpretation of the results

Proceedings under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules are characterized by lower costs of arbitration and a significantly shorter duration compared to those administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules.19 The analysis revealed a significantly higher settlement rate in cases under the SCC Arbitration Rules (18.5% as opposed to 11.5% under the SCC Expedited Arbitration Rules).

This may suggest that the expectation of a longer dispute resolution process promotes the parties’ efforts to find amicable settlement. It also suggests that the parties’ willingness to explore the prospects of settling their dispute is lower if they have already committed a significant proportion of the financial resources the case necessitates, and they anticipate a binding adjudication of their dispute in the near future.

An assessment of settlement rates per jurisdiction displayed that only parties from the UK (30%) were more likely to settle their dispute than those from the Nordics, especially Finland (26.3%), Norway (21.4%), and Denmark (14.3%). This finding may be taken as reflecting the deep roots of a cooperative approach to dispute resolution in the Nordic legal traditions. Remarkably, however, with a settlement rate of merely 8.2%, Swedish parties do not rank among the most common parties to settle disputes under the SCC Rules.

Meanwhile, the report found that the profile of settled cases largely reflects the overall SCC caseload and that the amount in dispute is not indicative of the likelihood of settlement. Disputes that result in settlement typically revolve around claims for below EUR 1 000 000.

It is worth noting that bifurcation and partial awards do not appear to (significantly) accelerate settlement. It is true that the considerable time spans between partial awards and the date of confirmed settlement may be explained by the complexity of these cases.20 However, this does not explain why partial awards seemed to mark only the half-way mark over the total course of the respective arbitration from initiation to settlement.

As regards the stages of the proceedings with the highest likelihood to successfully negotiate settlement, the report observed the highest settlement rates, either immediately before referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal or after the conclusion of the phase of written submissions. The high rate of pre-referral settlements suggests that the initiation of arbitral proceedings may at times serve to compel a party to return to the negotiating table – with success.

Yet, the analysis of post-referral settlements revealed that the exchange of written submissions in particular tends to trigger the parties’ to pursue a settlement. In fact, the greater the number of written submissions filed, the higher the success rate of the parties’ attempts at settlement. There are multiple approaches to interpret this finding.

For one, the written submissions compel the parties to acknowledge the strengths and weaknesses of their respective cases. For the first time, counsel will be in a position to realistically assess the prospects of success and the risks of their arguments. This coincides with the rapidly approaching hearing dates and thereby a substantial share of additional costs and expenses and consequently an increasing financial risk.

The fact that no settlements were recorded once the parties had conducted the hearing on the merits suggests that the oral hearings constitute a point of no return. Again, this is likely be explained by the size of the parties’ committed financial resources, which are linked to the conduct of the hearing on the one hand, and the mutual expectation of the imminent final award on the other.

Finally, that the number of settlements increases in the months immediately prior to the two main holiday periods in Sweden may not be surprising to those familiar with the Swedish way when it comes to annual leave and in particular the sanctity of the summer holiday period.

Conclusions

This report has examined settlement patterns in arbitrations administered under the SCC Rules concluded between 2021 and 2023. It showed that more than one in six arbitrations ended in settlement.

The findings confirm that settlement can offer substantial time savings, particularly in proceedings under the SCC Arbitration Rules, where the duration is essentially cut in half. Domestic disputes and parties from the UK and Nordic jurisdictions showed higher settlement rates, while the amount in dispute had little bearing on the likelihood of settlement. The analysis revealed two key moments when settlement most frequently occurs:

(i) immediately before referral of the dispute to the Arbitral Tribunal; and

(ii) following the final round of written submissions. These insights may

assist practitioners by providing empirical data to understand

settlement dynamics in institutional arbitration and to identify optimal

timing for settlement discussions.

In line with the SCC’s commitment to transparency and accountability, the findings from this report equip the users of arbitration with all possible information to resolve their disputes effectively and in the most efficient way possible. They also provide guidance to arbitrators on how the SCC considers the question of fees in the case of settlement. It is hoped that this report as well as the SCC’s continued commitment to promote efficient dispute settlement may encourage more parties to consider all available tools to resolve their disputes, including negotiating or mediating a settlement, such as under the SCC Rules, including the SCC Express.

Notes

1 The authors are grateful to Erik Erba Stenhammar and Leonardo Catovic for their invaluable contributions to this report

2 See the unofficial translation of the Act here: https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/the-swedisharbitration-act_1march2019_eng-2.pdf

3 Other EU jurisdictions which have adopted a similar approach include Belgium, Croatia, Czechia, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Slovakia, and Spain

4 Gabrielle Kaufmann-Kohler, When Arbitrators Facilitate Settlement: Towards a Transnational Standard’ in William W. Park (ed), Arbitration International, (The Author(s); Oxford University Press, 2009, Volume 25, Issue 2), pages 187 205 at page 195.

5 See, e.g., Klaus Peter Berger and J. Ole Jensen, “The Arbitrator’s Mandate to Facilitate Settlement”, International Commercial Arbitration Review (Association of Researchers in International Private and Comparative Law) Association of Researchers in International Private and Comparative Law 2017, Volume 2017, Issue 1), pp. 58 77 at page 58.

6 See, e.g., Rule 1.4 of the Civil Procedure Rules (1998) UK; Article 21 of the French Civil Procedure Code; Section 278(1) of the German Code of Civil Procedure; Section 33(1) of the Hong Kong Arbitration Ordinance; Section 17(1) of the Singapore International Arbitration Act

7 Sukma Dwi Andrina, “SCC Practice: Arbitration Costs in Settled Cases,” https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/wpcontent/uploads/2024/12/scc-practice-arbitration-costs-in-settled-cases.pdf

8 For example, in cases where the SCC must decide on its jurisdiction, the applicable rules, or the number of arbitrators to decide the case.

9 The analysis includes one case in which the Arbitral Tribunal neither expressly bifurcated the proceedings nor labelled its following decision as a separate award (but rather as a procedural order ). However, in the underlying case, the Arbitral Tribunal had asked the parties to exclusively submit on a specific set of substantive issues which it subsequently finally determined. Therefore, the report considered this an instance of a bifurcation and a subsequent partial award.

10 It should be pointed out that the report relies on the available statistics for the jurisdictions of parties in cases registered in the respective year instead of the cases concluded in the same time span. In other words, in this section the report compares the jurisdictions of parties in all cases settled between 2021 and 2023 with the jurisdictions of parties in all cases registered in the same period. This might ever so slightly distort the reliability of these findings but allows the report to infer the likelihood of settlement based on the home jurisdictions of the parties.

11 Otherwise, Belgian parties would have been the most frequent to settle their disputes as two out of five Belgian parties ended up agreeing on a settlement (a settlement rate of 40%). Thai parties were excluded from the present examination as their representation among the most represented parties is based on a one-off event of a series of 23 appearances in the same year based on the same factual background which would distort the results of the present analysis.

12 SCC, Statistics 2024, https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/statistics-2024/

13 See, e.g., SCC, Post M&A disputes take centre stage: A 2024 snapshot of the SCC’s caseload (15 May 2025) https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/news/post-ma-disputes-take-centre-stage-a-2024- snapshot-of-the-sccs-caseload/

14 Lowther, Nizzi and Delac, Costs of arbitration and apportionment of costs under the SCC Rules (October 2024) , p. 20

15 Cf. above at section 2.5

16 Typically, in the time allocated for the parties’ discussions on a suitable sole arbitrator or chairperson.

17 For further information, see the SCC’s report on Costs of arbitration and apportionment of costs under the SCC Rules (2024) available here: https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/report_costs_of_arbitration_final-2.pdf , pp.11-12.

18 For further information, see the SCC’s report on Costs of arbitration and apportionment of costs under the SCC Rules (2024) available here: https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/report_costs_of_arbitration_final-2.pdf, pp. 11-12

19 In fact, in 2023, the final year under the time span assessed in this report, all cases administered under the Expedited Arbitration Rules were concluded within six months, see: https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/statistics-2023/.

20 An average dispute that was bifurcated and subsequently settled took an average of 895 days (median: 554 days) in total and (insofar as the complexity of a case may be expressed taking recourse to the disputed amounts) concerned an amount of EUR 38.4 million (median: EUR 32.2 million).