Costs of arbitration and apportionment of costs under the SCC Rules

Authors: Jake Lowther, Lorenzo Nizzi, and Samuel Hörberg Delac1

Table of contents

- Costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation under the SCC Arbitration rules

- What are the costs of arbitration?

- How are the advance on costs calculated?

- Achieving balance

- Amount in dispute and number of arbitrators

- Sole arbitrator

- Three arbitrators

- Combined figures

- Getting the big picture – Median and mean values of costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation

- Sole arbitrator

- Three arbitrators

- Duration of disputes

- Costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation under the SCC rules for Expedited Arbitrations

- What are the costs of arbitration?

- How are the advance on costs calculated?

- Achieving balance

- Amount in dispute

- Getting the big picture – Median and mean values of costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation

- Duration of disputes

- Apportionment of costs of arbitration and costs for legal represetation

- Legal standard for the apportionment of costs

- SCC Arbitration Rules

- SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations

- Apportionment of costs on the basis of the outcome of the case

- Partial apportionment

- Standard apportionment

- Nationality of arbitrators

- Apportionment of costs on the basis of party conduct

- Awarding costs for legal representation

- Considerations of Decision Makers when adjusting the costs for legal representation

Background

Arbitration has, particularly in the international context, for many years been perceived as taking longer and becoming increasingly expensive. In 2016, in response to these concerns, as well as the fact that many arbitration users are not aware of the costs that each stage of a dispute will entail or that most of the costs incurred are within their control, the SCC Arbitration Institute (“SCC”) released a report on the costs of arbitration and apportionment of costs under the SCC Arbitration Rules (“2016 Report”).2

As stated in the 2016 Report, “on the one hand, the costs of arbitrationare determined by the claims that the parties choose to raise, and, on the other hand, the costs for legal representation are to a great extent determined by the conscious decisions that parties make when choosing their case strategy.”

The 2016 Report was based on a review of 80 arbitral awards rendered between 2007 and 2014 under the SCC Arbitration Rules containing reasoned decisions on costs, and concluded inter alia that, in SCC cases with a sole arbitrator a median of 65% of the total costs paid by the parties corresponded to costs for legal representation, whereas a median of 35% was covered the costs of arbitration. In cases with three arbitrators, a median of 81% out of the total costs was for legal representation, with the remaining 19% referring to the costs of arbitration.

With the aim of continuing its efforts to increase confidence and transparency in arbitration and the SCC’s practice, this report is an update of the 2016 Report (“2024 Report”), providing data on the size of disputes, their duration, and costs, as well as how Arbitral Tribunals and Arbitrators have ultimately apportioned the costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation.

The 2024 Report is based on an analysis of 221 cases rendered between 2015 and 2022. For the first time, data will also be provided on the costs of arbitration and apportionment of costs under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations. The 2024 Report will therefore also be able to compare and draw conclusions in respect to all arbitrations conducted under the SCC Rules.

Mindful of the ongoing concerns about the rising cost of arbitration as well as of the importance of providing fair and competitive remuneration to arbitrators, as of 1 January 2024, a revised schedule of costs entered into force at the SCC, entailing an increase in the fees for arbitrators handling cases under the SCC Rules.3 During the period of the 2024 Report, two revisions of the SCC Rules and three revisions of the SCC’s schedules of costs took place, resulting inter alia in increases to the fees of the arbitrators and the SCC.

Moreover, the SCC is committed to innovation in dispute resolution to ensure a better process for its users, and to providing the “right tool for the right dispute”. For example, in 2021 the SCC launched its SCC Express Dispute Assessment service, “SCC Express”. 4 The SCC continues to monitor the issue of costs with the aim of ensuring a better process and value for users, and appropriate remuneration for arbitrators.

As the 2024 Report demonstrates, the costs of arbitration in cases administered under the SCC Rules have in comparison to the 2016 Report significantly decreased as a proportion of the total cost. This indicates that the SCC Rules and arbitration “the Swedish way” continue to be market-leading in ensuring efficiency (particularly on cost) and efficacy in arbitration.

Material and methodology

- A total of 1 428 cases were registered by the SCC between 2015 and 2022.5

- Of these cases, a total of 1 304 domestic and international disputes were administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules and the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations. These cases were reviewed in the preparation of the 2024 Report.

- In line with the 2016 Report, arbitral awards rendered during this period lacking full information on party claims for costs for legal representation, consent awards, and awards recording the termination of the arbitration were excluded from the 2024 Report.

- After applying these delimitations to the 1 304 cases, the 2024 Report consists of a final data pool of 221 qualifying arbitral awards.

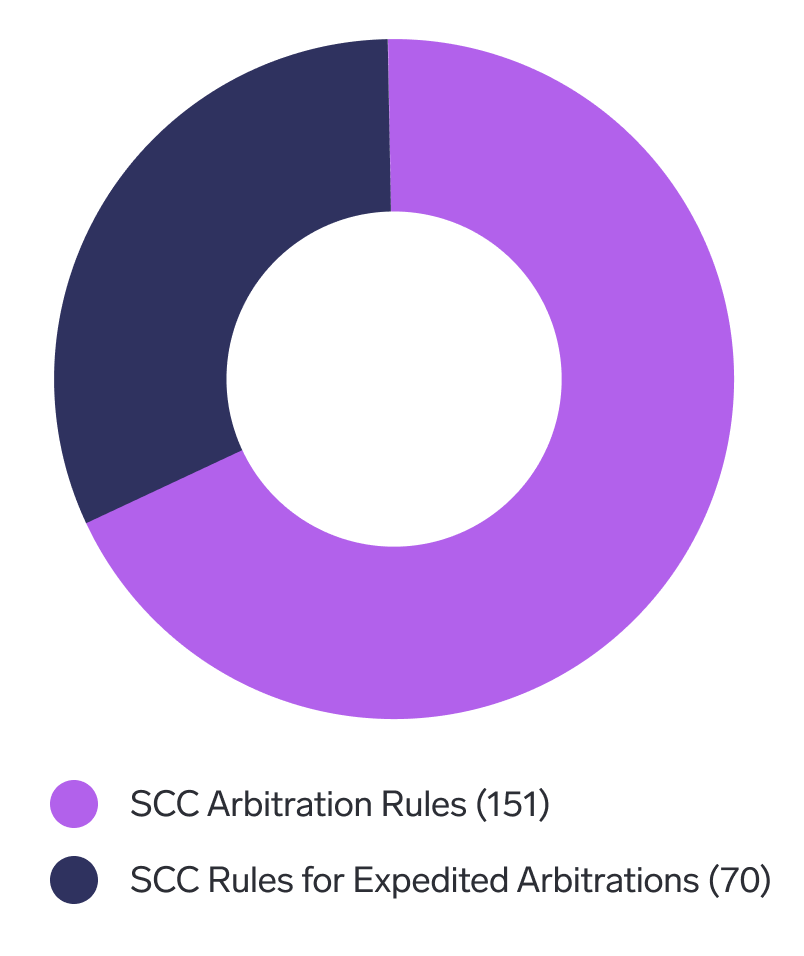

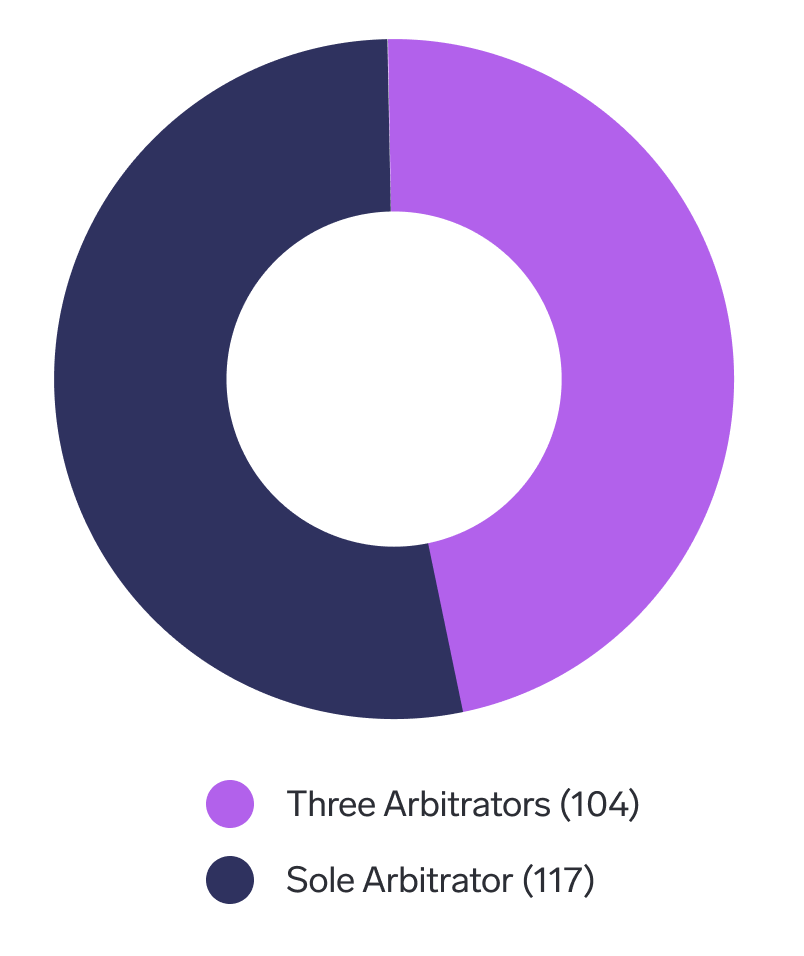

- Of these 221 arbitral awards, 151 were rendered under the SCC Arbitration Rules (see figure 1), of which 47 were decided by an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of a sole arbitrator and 104 were decided by an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of three arbitrators (see figure 2).

- In the remaining 70 cases, the final award was rendered by an Arbitrator, i.e., an arbitrator appointed under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations (see figure 1).

- This reflects the SCC’s typical annual caseload in which approximately one third of cases are registered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations and approximately two thirds of cases are registered under the SCC Arbitration Rules.

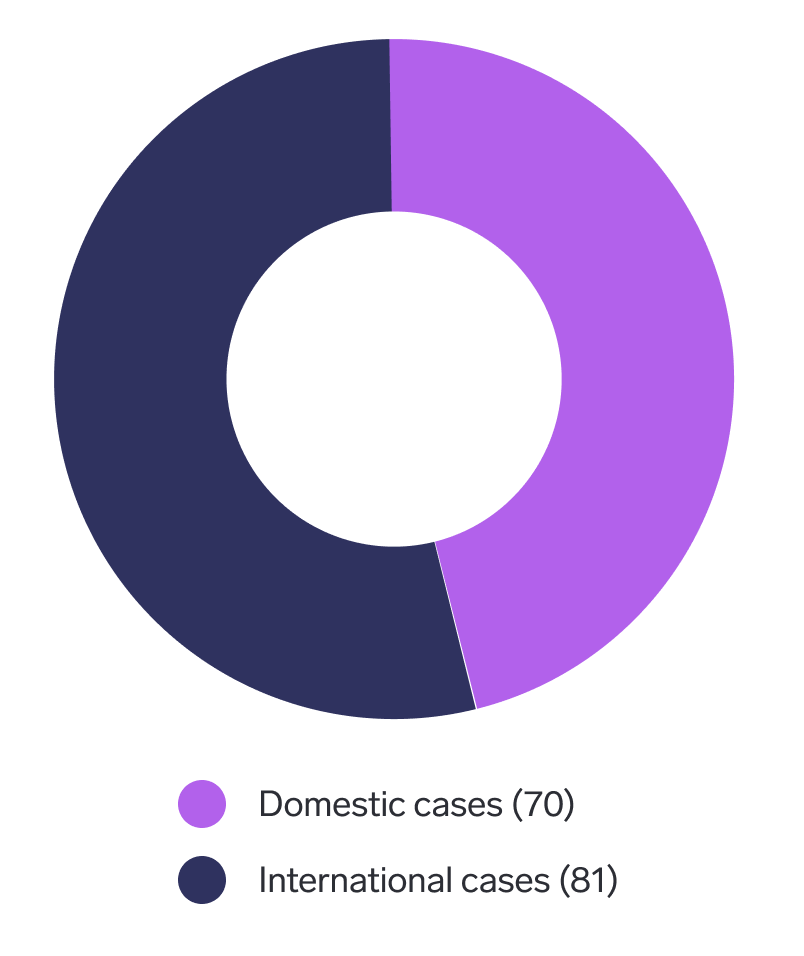

- A total of 24 out of the 47 sole arbitrator cases and 46 out of the 104 three-arbitrator cases administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules (46,4%) were domestic, with the remaining cases (53,6%) international, i.e., at least one of the parties was not Swedish (see figure 3).

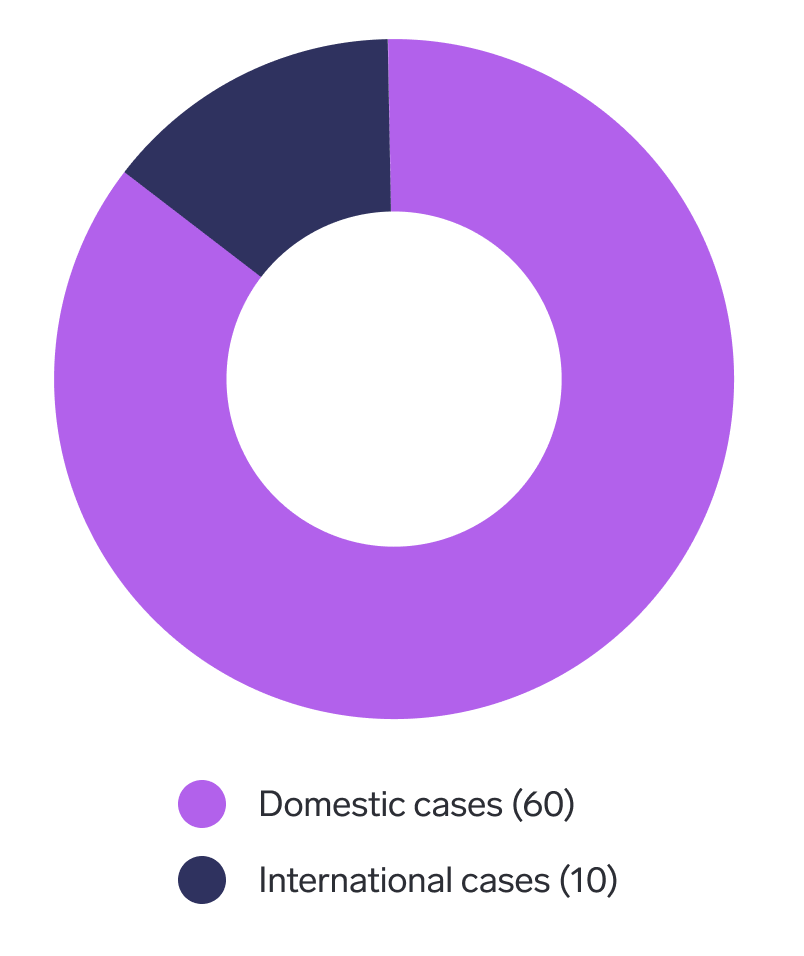

- A total of 60 out of the 70 cases decided under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations were domestic (85,7%), with the remaining 10 cases international, i.e., at least one of the parties was not Swedish. (see figure 4)

- A total of 429 arbitrators were appointed under the SCC Rules to decide these 221 cases, either by the parties, the party-appointed coarbitrators, or the SCC Board.

- Of these arbitrators 43,4% were Swedish. This represents an overall decrease in the number of Swedish arbitrators, and a corresponding increase in the number of international arbitrators, compared to the 2016 Report (54,3%). This result is despite the inclusion of qualifying cases administered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, the majority of which have been domestic. It demonstrates the continuing internationalisation of arbitration under the SCC Rules.

- In the interests of transparency and given the fact that there can be large variations between the total values in dispute in cases administered under the SCC Rules, the 2024 Report includes both the mean and median values of various data points. Percentages have been rounded to within one decimal place.

The 2024 Report

Part III of this 2024 Report presents statistical data on the costs of arbitration and on the time to render the award in cases decided by a sole arbitrator and by three arbitrators under the SCC Arbitration Rules.

Part IV of this 2024 Report presents statistical data on the costs of arbitration and on the time to render the award in cases decided under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations.

Part V of this 2024 Report presents statistical data on the recoverability of the parties’ costs. It describes how arbitrators have apportioned the costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation in the awards reviewed, as well as the nationality of the arbitrators under the SCC Rules.

Part VI of this 2024 Report provides some concluding remarks based on the data analysed, including comparisons with the conclusions of the 2016 Report.

Definitions

For the purposes of this 2024 Report:

“2016 Report” is the SCC’s report on the costs of arbitration and apportionment of costs under the SCC Arbitration Rules published in 2016.

“2024 Report” is the SCC’s report on the costs of arbitration and apportionment of costs under the SCC Rules published in 2024.

“costs of arbitration” are the aggregate value of the Arbitral Tribunal’s fees and the SCC administrative fee as finally set in the cost order contained in an award;

“costs for legal representation” are the aggregate value of the costs claimed by the claimant and the respondent for legal fees only. This report excludes costs incurred for expenses by the parties, counsel, the Arbitral Tribunal, and the SCC. The amounts presented in this report exclude VAT;

“Decision Maker” refers to Arbitral Tribunals and Arbitrators appointed under the SCC Rules.

“Formula” refers to the mathematical formula adopted by the SCC to determine the costs of arbitration for disputes under the SCC Rules;

“SCC” refers to the SCC Arbitration Institute; and

“SCC Rules” refers to the SCC Arbitration Rules and the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations.

All other capitalized terms are as defined in the SCC Rules.

Introduction

The 2024 Report is based on an analysis of 221 qualifying arbitral awards rendered between 2015 and 2022. This is out of a total of 1 428 cases registered by the SCC during the period, of which 1 304 were cases administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules and the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations. It is worth bearing in mind that during this period, two revisions of the SCC Rules and three revisions of the SCC’s schedules of costs also took place.

The breakdown of the 221 qualifying arbitral awards rendered under the respective rules is as follows.

Number of qualifying arbitral awards rendered under the SCC Arbitration Rules (151 cases):

- A total of 47 were decided by a sole arbitrator (23 international; 24 domestic).

- A total of 104 were decided by three arbitrators (58 international; 46 domestic).

- During the period, a total of 53,6% of the qualifying arbitral awards rendered under the SCC Arbitration Rules were international and 46,4% were domestic.

This represents a significant increase in the number of qualifying domestic cases compared to the 2016 Report (2 domestic cases decided by a sole arbitrator, and 7 domestic cases by three arbitrators), which suggests a greater harmonization and internationalisation of Swedish practice.

Number of qualifying arbitral awards rendered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations (70 cases):

- A total of 10 were international cases and 60 were domestic cases, which is in line with the Swedish market’s noted usage and preference for expedited arbitration under the SCC Rules.

The SCC is seeing an increasing number of parties requesting arbitration based on the SCC’s so-called “combination clauses”, the predominant of which provides the SCC Board with the discretion to determine the rules based on the circumstances of the case.6

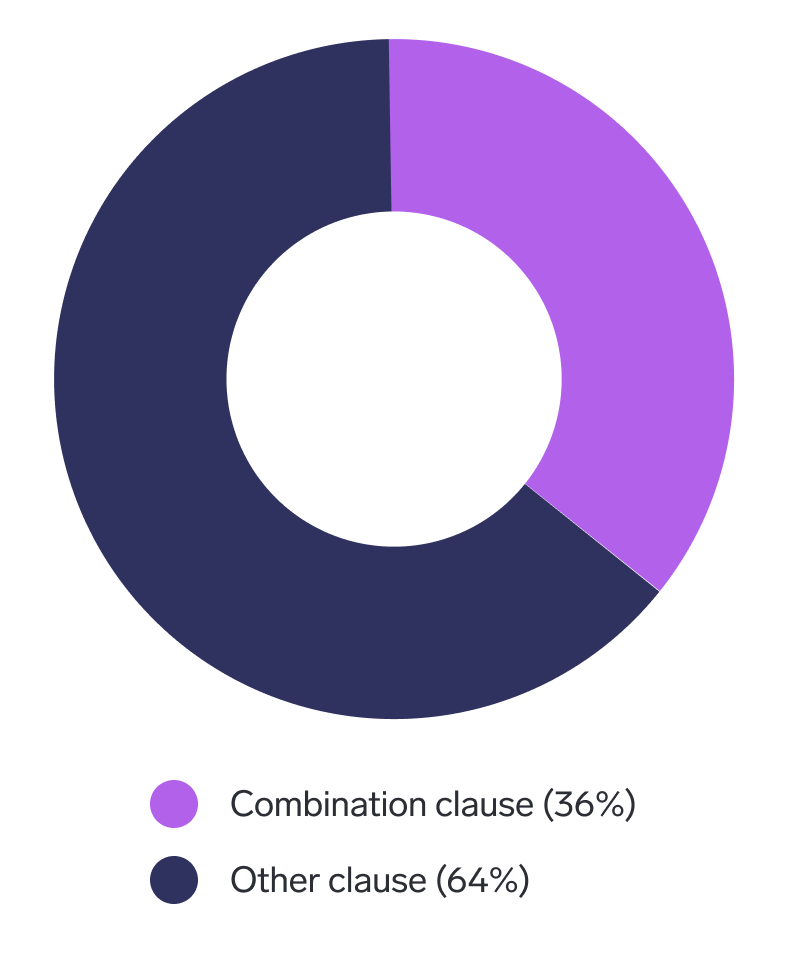

Of the 70 qualifying cases administered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, 25 (36%) were requested on the basis of one of the SCC’s combination clauses, with the vast majority of these invoked clauses (88%) provided the SCC Board with the discretion to determine the rules based on the circumstances of the case. The remainder (12%) applied a monetary threshold.

Costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation under the SCC Arbitration rules

Part I of this 2024 Report presents statistical data on the costs of arbitration and on the time to render the award in cases rendered under the SCC Arbitration Rules.

Pursuant to Article 16, in the absence of party agreement, the Arbitral Tribunal in cases administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules shall consist of a sole arbitrator or three arbitrators, having regard to the complexity of the case, the amount in dispute and any other relevant circumstances. For example, cases where the amount in dispute is under EUR 1 million will in general be decided by a sole arbitrator. Otherwise, the SCC Board undertakes a case-by-case analysis.

What are the costs of arbitration?

According to Article 49 (1) SCC Arbitration Rules, the costs of arbitration consist of:

(i) the fees of the Arbitral Tribunal,

(ii) the administrative fee,

(iii) the expenses of the Arbitral Tribunal and the SCC.

Pursuant to Article 51, the parties are requested to pay an amount as advance on costs, which corresponds to the estimated amount of the costs of arbitration. Pursuant to Article 22, the payment of the advance on costs is a necessary condition for the referral of the case to the Arbitral Tribunal.

In accordance with the SCC Arbitration Rules, where one of the parties fails to pay its share of the advance on costs, the other party will be invited to do so. Such party may then request a separate award from the Arbitral Tribunal for the reimbursement of the payment after the referral of the case. A failure to pay the advance on costs in full may result in the dismissal of certain claims and or counterclaims, or even of the case in full.

How are the advance on costs calculated?

The fees of the Arbitral Tribunal, the SCC’s administrative fee and a reserve for potential expenses are set on the basis of the amount in dispute in line with the table of costs contained in Appendix IV of the SCC Arbitration Rules.

The amount in dispute includes the aggregate value of all claims, counterclaims, and set offs raised by the parties to the arbitration (Articles 2 (3) and 3 (2) Appendix IV SCC Rules). With this, the SCC has adopted an ad valorem table of costs system to calculate the costs of the arbitration. The table of costs consists of a mathematical formula (“Formula”) for disputes amounting from up to EUR 25 000 and up to EUR 100 million. The advance on costs for disputes exceeding EUR 100 million is set by the Board on a case-by-case basis.

The Formula depends on two basic factors: the amount in dispute, which establishes the range of the table of costs within which the fees will be calculated, and the complexity of the dispute, which establishes the level at which the fees may be set.

Factors that may be considered in assessing the complexity of a dispute include whether the Arbitral Tribunal will have to deal with any jurisdictional objection, whether the dispute involves multiple parties, multiple contracts, or multiple claims, the nationality of the parties, the subject matter of the dispute, and whether it is likely that much documentary evidence will be submitted, or several witnesses will be heard.

The SCC has made available to parties a costs calculator on its website to provide additional transparency and predictability around cost for parties contemplating initiating an arbitration under the SCC Rules.7

Achieving balance

The fees of the Arbitral Tribunal vary in general from a minimum to a maximum level.

Depending on the complexity of each case, the SCC determines the fees anywhere between the two levels. In practice, these levels vary between minimum, median and maximum, with median values in-between these levels.

In exceptional circumstances, the SCC may deviate from the amounts set out in the table of costs when determining the fees, for example where the complexity and scope of the case justify a fee level beyond the maximum.

Amount in dispute and number of arbitrators

It should come as no surprise that the costs of arbitration in disputes decided by an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of three arbitrators are higher than those incurred in a dispute resolved by an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of a sole arbitrator. Having two additional persons deciding the dispute not only entails higher fees but can also be an indication that the dispute is more complex. Where higher amounts are at stake, the dispute often requires careful consideration by three experienced arbitration practitioners.

According to the SCC’s practice, in the case of an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of three arbitrators, each of the co-arbitrator in general receives 60% of the chairperson’s fee. However, after consultation with the Arbitral Tribunal, the Board may decide that another rate shall apply.

Generally, parties refer their disputes to an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of a sole arbitrator when the dispute is of a simpler character and when the amounts at stake are relatively low.

Of course, exceptions to this general rule exist, and occasionally parties may leave adjudication of high value claims to a sole arbitrator. The following is a summary of the data obtained from the cases reviewed in this 2024 Report.

Sole arbitrator

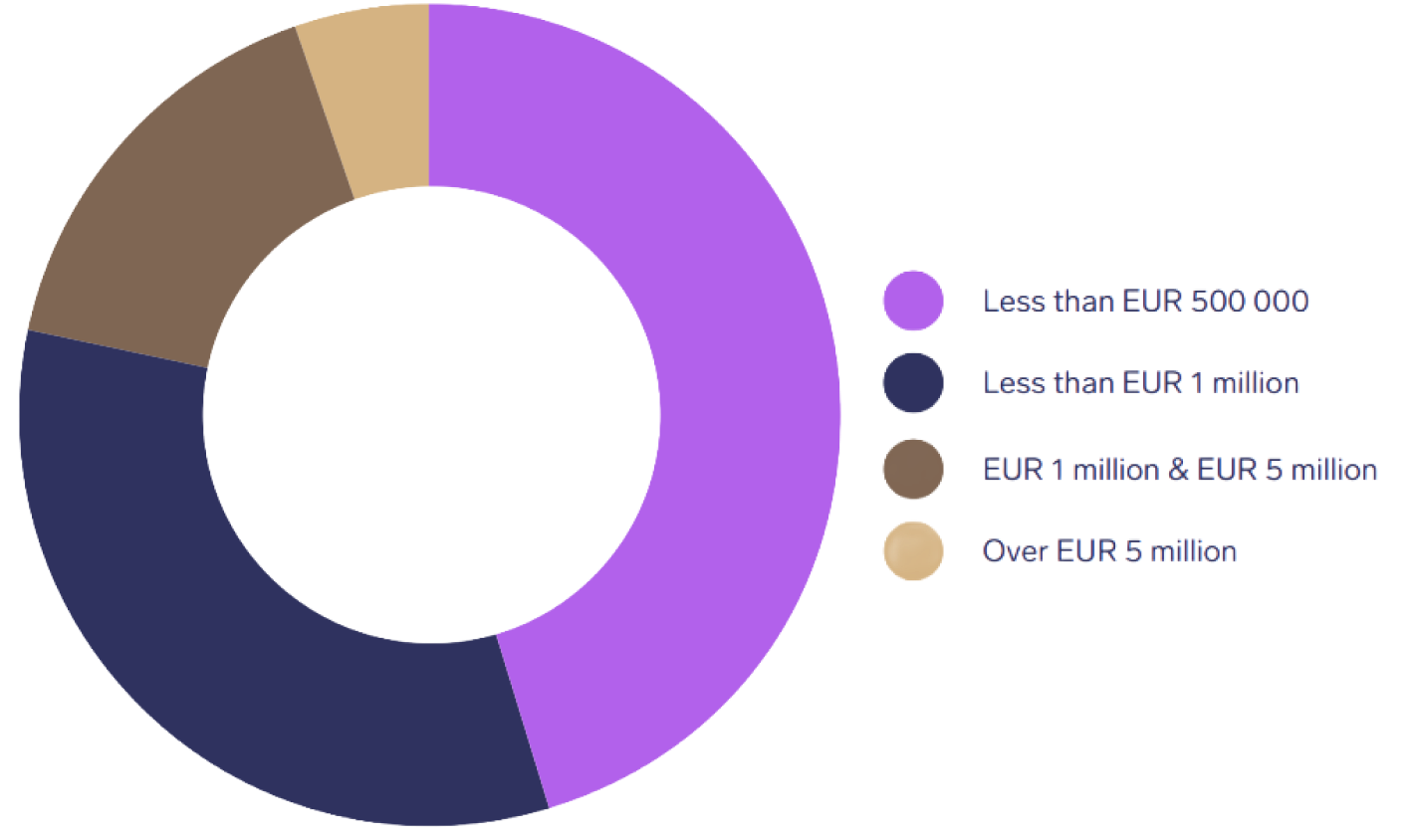

According to the 2024 Report’s breakdown of the cases decided by an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of a sole arbitrator under the SCC Arbitration Rules by amount in dispute, the results appear to be broadly in line with the 2016 Report, with a trend towards slightly higher amounts in dispute.

- The majority of these cases (70%) concerned an amount in dispute below EUR 1 million (compared to 78% in the 2016 Report).

- In most of these cases (51%) the amounts at stake did not exceed EUR 500 000 (compared to 59% in the 2016 Report).

- 25,5% of these cases had an amount in dispute that ranged between EUR 1 million and EUR 5 million (compared to 19% in the 2016 Report).

- In only 8,5% of these cases was the amount in dispute over EUR 5 million (compared to 4% in the 2016 Report).

- The median amount in dispute was EUR 470 503. By way of comparison, the median amount in dispute for all cases decided by an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of a sole arbitrator under the SCC Arbitration Rules during the period was EUR 361 229.

- The mean amount in dispute was EUR 2 530 694. By way of comparison, the mean amount in dispute for all cases decided by an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of a sole arbitrator under the SCC Arbitration

Rules during the period was EUR 1 293 692,3.

For the purposes of illustration, pursuant to the SCC’s 2024 table of costs an amount in dispute of EUR 470 503 results in an Arbitral Tribunal’s fee (median) of EUR 24 485 and an administrative fee of the SCC of EUR 13 556. However, as stated above, these figures vary in practice based on the circumstances of the case.

Three arbitrators

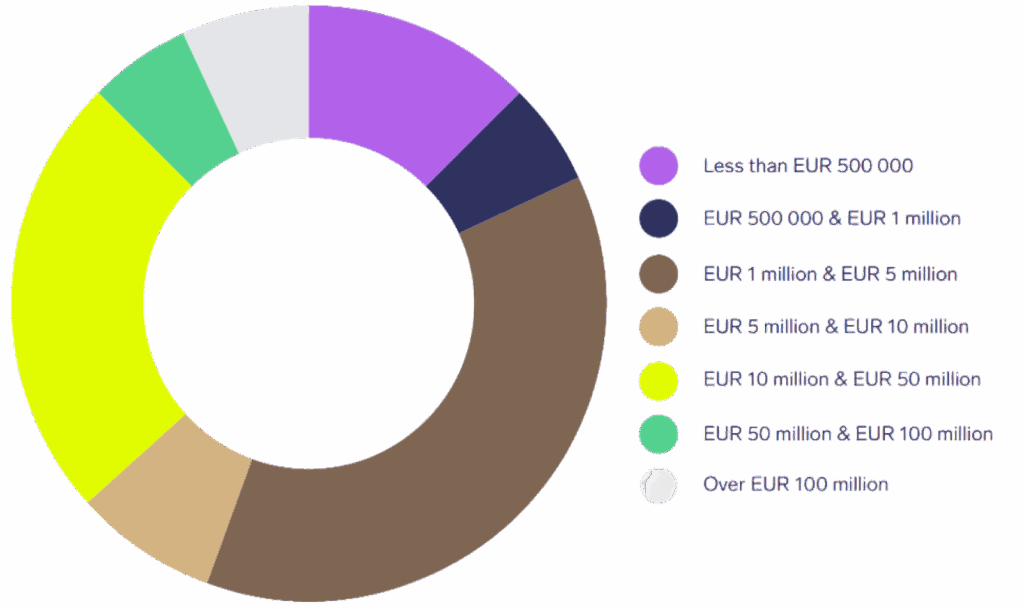

The breakdown of the cases decided by an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of

three arbitrators under the SCC Arbitration Rules by amount in dispute is

also broadly in line with the 2016 Report, with a broad trend towards higher amounts in dispute, although with a greater deviation than in the case

of an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of a sole arbitrator.

- In 12,5% of these cases, the amount in dispute did not exceed EUR 500 000 (compared to 13% in the 2016 Report).

- 5,8% of these cases concerned an amount in dispute between EUR 500 000 and EUR 1 million (compared to 15% in the 2016 Report).

- 37,5% of these cases concerned an amount in dispute ranging between EUR 1 million and EUR 5 million (compared to 32% in the 2016 Report).

- In 7,7% of these cases, the amount in dispute ranged from EUR 5 to EUR 10 million (compared to 9% in the 2016 Report).

- 24% of these cases concerned an amount in dispute between EUR 10 up to EUR 50 million (compared to 18% in the 2016 Report).

- In 5,8% of these cases, the amount in dispute ranged up to EUR 100 million (compared to 3,7% in the 2016 Report).

- 6,7% of these cases concerned an amount exceeding EUR 100 million (compared to 7,5% in the 2016 Report).

- The median amount in dispute was EUR 3 734 990. By way of comparison, the median amount in dispute for all cases decided by an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of three arbitrators under the SCC Arbitration Rules during the period was EUR 4 036 634.

- The mean amount in dispute was EUR 65 822 478,8. By way of comparison, the mean amount in dispute for all cases decided by an Arbitral Tribunal comprised of three arbitrators under the SCC Arbitration Rules during the period was EUR 79 608 088,3.

Combined figures

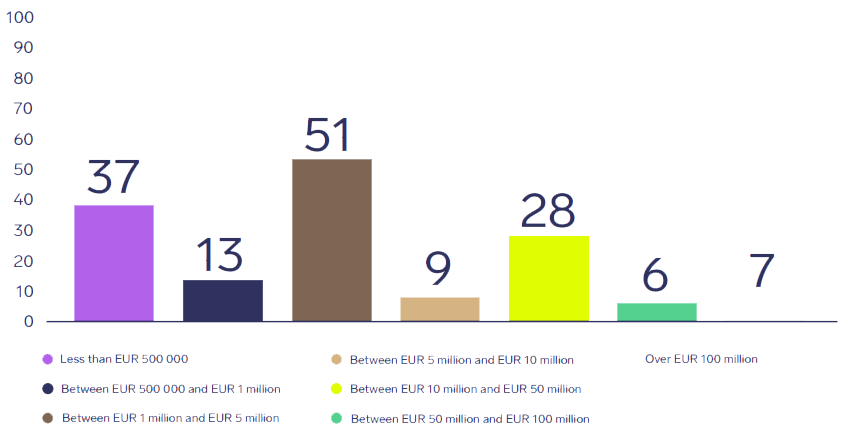

A breakdown of all the cases decided under the SCC Arbitration Rules by amount in dispute is as follows:

- Less than EUR 500 000: 37 cases

- Between EUR 500 000 and EUR 1 million: 13 cases

- Between EUR 1 million and EUR 5 million: 51 cases

- Between EUR 5 million and EUR 10 million: 9 cases

- Between EUR 10 million and EUR 50 million: 28 cases

- Between EUR 50 million and EUR 100 million: 6 cases

- Over EUR 100 million: 7 cases

- The median amount in dispute was EUR 2 096 060. By way of com parison, the median amount in dispute for all cases decided under the SCC Arbitration Rules during the period was EUR 1 496 880.

- The mean amount in dispute was EUR 45 686 476. By way of comparison, the mean amount in dispute for all cases decided under the SCC Arbitration Rules during the period was EUR 51 943 782,2.

For the purposes of illustration, pursuant to the SCC’s table of costs an amount in dispute of EUR 2 096 060 results in an Arbitral Tribunal’s fee (median) of EUR 121 407 in the case of three arbitrators, or EUR 55 185 in the case of a sole arbitrator, and an administrative fee of the SCC of EUR 29 671. However, as stated above, these figures vary in practice based on the circumstances of the case.

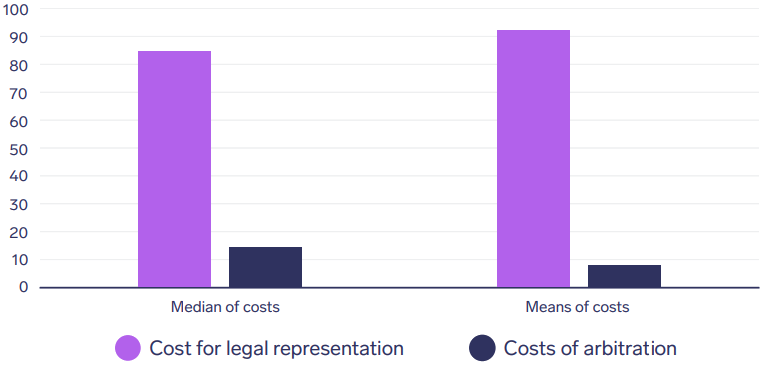

Getting the big picture – Median and mean values of costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation

In line with the 2016 Report, the costs for legal representation form the main part of a party’s costs during the dispute.

Sole arbitrator

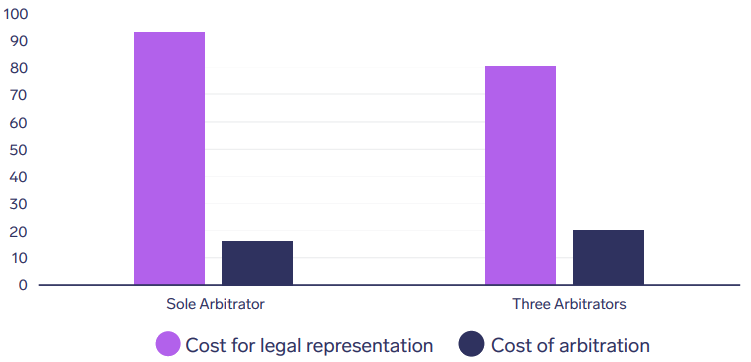

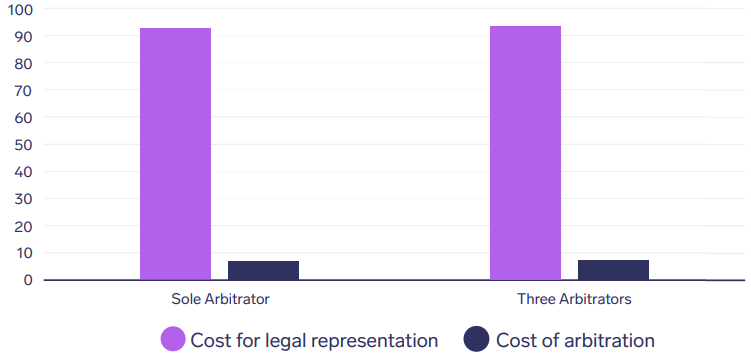

- In cases with a sole arbitrator, a median percentage of 93,6% of the total costs paid by the parties corresponded to costs for legal representation, whereas a median percentage of 15,8% was paid for the costs of arbitration.8

- In cases with a sole arbitrator, a mean percentage of 93,1% of the total costs paid by the parties corresponded to costs for legal representation, whereas a mean percentage of 6,9% was paid for the costs of arbitration.

- In terms of size, in disputes with a sole arbitrator the median costs for legal representation were 5,9 times higher than the median arbitration costs.

- In terms of size, in disputes with a sole arbitrator the mean costs for legal representation were 13,5 times higher than the mean arbitration costs.

Three arbitrators

Out of the total costs spent in an arbitration with three arbitrators, a median percentage of 80,8% was paid for costs for legal representation, with 19,2% devoted to pay the costs of arbitration.9 Out of the total costs spent in an arbitration with three arbitrators, a mean percentage of 92,8% was paid for costs for legal representation, with the remaining 7,2% devoted to pay the costs of arbitration. In disputes decided by three arbitrators, the median costs paid for legal representation were 4,1 times the median arbitration costs. In disputes decided by three arbitrators, the mean costs paid for legal representation were 12,85 times the mean arbitration costs. A comparison with the 2016 Report thus demonstrates that the pace of increases to the parties’ legal representation costs far outstrips the increase in the costs of arbitration.

Duration of disputes

The duration of an arbitration is measured from the date of the registration of the case by the SCC Secretariat until the date when the Arbitral Tribunal renders the final award.

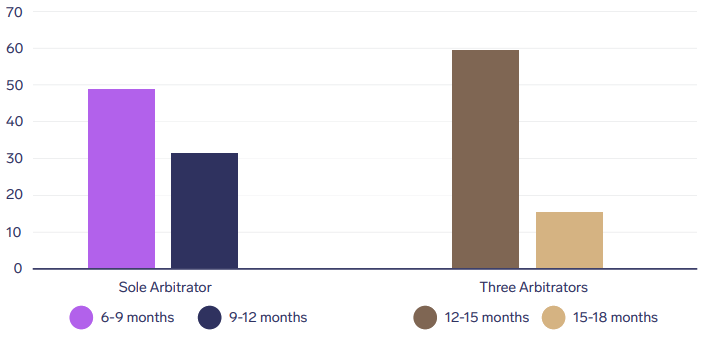

The data shows that there is a predominance of short-duration disputes, with some outlier cases that distorts the average values for the duration of disputes. For this reason, more meaningful data on the duration of disputes is obtained by looking at the median duration of disputes decided by sole and three arbitrators. However, for the sake of transparency, the mean values have also been included in this 2024 Report.

- The 2024 Report reveals that the median duration of disputes decided by sole arbitrators is 7 months (10,3 months in the 2016 Report) and 10 months for disputes decided by three arbitrators (15,8 months

in the 2016 Report). Looking at all cases, the median duration was 10 months (13,5 months in the 2016 Report). - By way of comparison, the mean duration of disputes decided by sole arbitrators is 10,2 months and 18,5 months for disputes decided by three arbitrators. Looking at all cases, the mean duration was 16 months.

- For context, in 2023 65% of arbitral awards under the SCC Arbitration Rules were rendered within 12 months.

While median values provide a “big picture” of disperse data, looking at the percentage of cases decided within a specific time span provides more accurate information on the duration of sole and three-arbitrator disputes.

- Looking at sole arbitrator cases in more detail, the data indicates that 78,2% of these cases were decided within 6-12 months from registration (48,9% within 6-9 months and 31,2% within 9-12 months). This compares to 66,6% in the 2016 Report.

- 70,2% of Arbitral Tribunals comprised of three arbitrators rendered the award within 12-18 months from registration (59,6% within 12-15 months and 15,4% within 15-18 months). This compares to 43,3% in the 2016 Report.

- In approx. 43% of cases, the award was rendered within 6-12 months of registration.

The 2024 Report thus clearly demonstrates that the duration of SCC arbitrations has measurably decreased since 2016. This is likely due in part to the SCC’s innovations in efficiency, with the introduction of the SCC’s

internal digital administration system in 2013 and in 2019 the launch of the SCC Platform, a cybersecure online case management system, among others.

Costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation under the SCC rules for Expedited Arbitrations

Part II of this 2024 Report presents statistical data on the costs of arbi tration and on the time to render the award in cases rendered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations.

What are the costs of arbitration?

According to Article 49 (1) SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, the costs of arbitration consist of:

(i) the fees of the Arbitrator,

(ii) the administrative fee,

(iii) the expenses of the Arbitrator and the SCC.

Pursuant to Article 51, the parties are requested to pay an amount as ad vance on costs, which corresponds to the estimated amount of the costs of arbitration. Pursuant to Article 23, the payment of the advance on costs is a necessary condition for the referral of the case to the Arbitrator. In accordance with the SCC Arbitration Rules, where one of the parti es fails to pay its share of the advance on costs, the other party will be invited to do so. Such party may then request a separate award from the Arbitrator for the reimbursement of the payment after the referral of the case. A failure to pay the advance on costs in full may result in the dismis sal of certain claims and or counterclaims, or even of the case in full.

How are the advance on costs calculated?

The fees of the Arbitrator, the SCC’s administrative fee and a reserve for potential expenses are set on the basis of the amount in dispute in line with the table of costs contained in Appendix III of the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations.

The amount in dispute includes the aggregate value of all claims, counter claims, and set offs raised by the parties to the arbitration (Articles 2 (3) and 3 (2) Appendix III SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations). With this, the SCC has adopted an ad valorem system to calculate the costs of the arbitration.

The table of costs consists of a mathematical formula (“Formula”) for disputes amounting from up to EUR 25 000 and up to EUR 5 million. The advance on costs for disputes exceeding EUR 5 million is set by the Board on a case-by-case basis. The Formula depends on two basic factors: the amount in dispute, which establishes the range of the table of costs within which the fees will be calculated, and the complexity of the dispute, which establishes the level at which the fees may be set.

Factors that may be considered in assessing the complexity of a dispute include whether the Arbitrator will have to deal with any jurisdictional objection, whether the dispute involves multiple parties, multiple contracts, or multiple claims, the subject matter of the dispute, and whether it is likely that much documentary evidence will be submitted, or that an oral hearing will be held.

Achieving balance

The fees of the Arbitrator in general vary from a minimum to a maximum level.

Depending on the complexity of each case, the SCC determines the fees anywhere between the two levels. In practice, these levels vary between minimum, median and maximum, with median values in-between these levels.

In exceptional circumstances, the SCC may deviate from the amounts set out in the table of costs when determining the fees, for example where the complexity and scope of the case justify a fee level beyond the maximum.

Amount in dispute

Cases administered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations are decided by the Arbitrator, i.e. a sole arbitrator. The SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations were developed to save parties time and cost where a standard arbitration would be less appropriate, such as when the dispute is of a simpler character and when the amounts at stake are relatively low.

Of course, exceptions to this general rule exist, and occasionally parties may leave adjudication of high value claims to an Arbitrator under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations. In line with the principle of party autonomy, the SCC will administer such cases in accordance with the parties’agreement.10

Moreover, the SCC is seeing an increasing number of parties requesting arbitration based on agreements to the SCC’s so-called combination clauses, the predominant of which provides the SCC with the discretion to determine the which rules shall apply based on the circumstances of the case.11

Of the 70 qualifying cases administered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, 25 (36%) were requested on the basis of one of the SCC’s combination clauses, with the vast majority of these invoked clauses (88%) provided the SCC Board with the discretion to determine the rules based on the circumstances of the case. The remainder (12%) applied a monetary threshold.

The following is a summary of the data obtained from the cases reviewed in this 2024 Report.

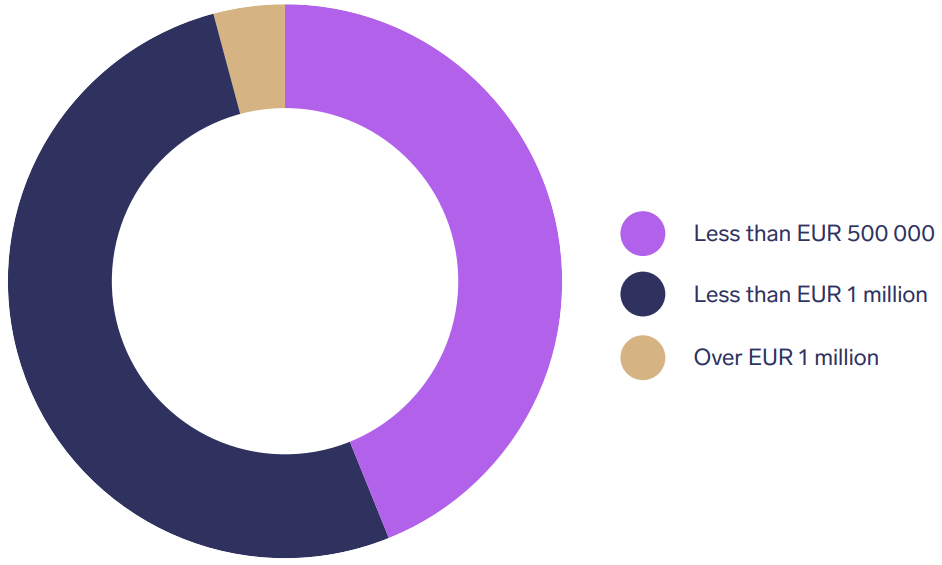

- A large majority of 92,8% of the cases decided under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations had an amount in dispute below EUR 1 million.

- The amounts in dispute in 80% of cases did not exceed EUR 500 000.

- Only 7,1% of cases concerned an amount in dispute over EUR 1 million.

- The median amount in dispute was EUR 139 151. By way of comparison, the median amount in dispute for all cases decided by an Arbitrator under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations during the period

was EUR 162 240,5. - The mean amount in dispute was EUR 321 883. By way of comparison, the mean amount in dispute for all cases decided by an Arbitrator under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations during the period was

EUR 837 744,9.

This reflects the SCC’s experience that the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations are most appropriate for disputes that are of lower-value, complexity and narrower in scope.

For the purposes of illustration, pursuant to the SCC’s table of costs an amount in dispute of EUR 139 151 results in an Arbitrator’s fee (median) of EUR 8 922 and an administrative fee of the SCC of EUR 5 176. However, as stated above, these figures vary in practice based on the circumstances of the case.

Getting the big picture – Median and mean values of costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation

It remains the case that the costs for legal representation form the main part of a party’s costs during the dispute.

- In cases decided under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, a median percentage of 84,5% of the total costs paid by the parties corresponded to costs for legal representation, whereas a median percentage of 14% was paid for costs of arbitration.12

- A mean percentage of 91,4% of the total costs paid by the parties corresponded to costs for legal representation, whereas a mean percentage of 8,6% was paid for costs of arbitration.

- In terms of size, in disputes decided under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, the median costs for legal representation were 6 times higher than the median arbitration costs.13

- The mean costs for legal representation were 10,6 times higher than the mean arbitration costs.

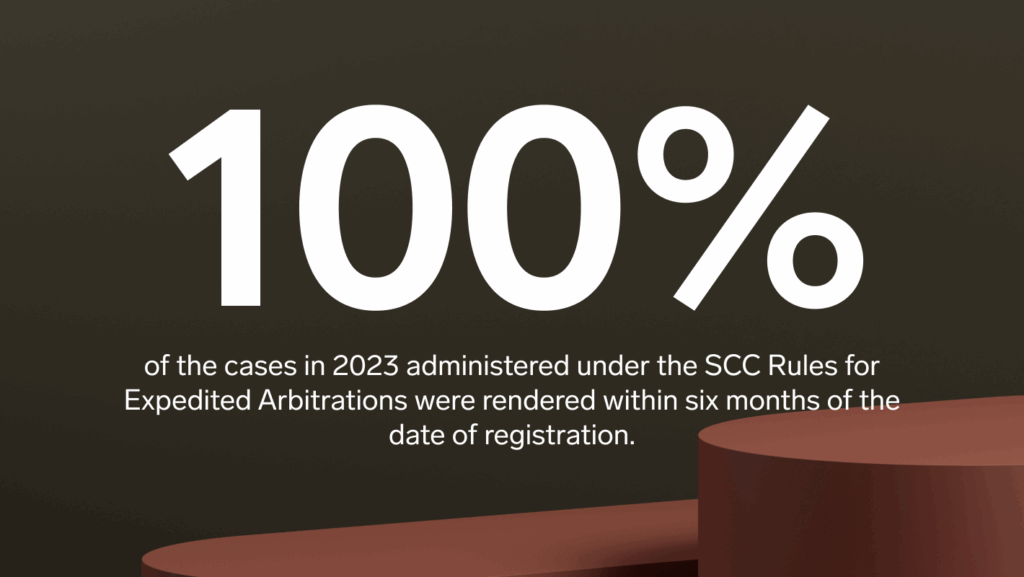

Duration of disputes

The duration of an arbitration is measured from the date of the registration of the case by the SCC Secretariat until the date when the Arbitrator renders the final award.

Under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, cases are “frontloaded”, in that the request for arbitration and the answer thereto constitute the statement of claim and the statement of defence, respectively, in order to save time while also ensuring the rights of the parties to be heard.

As a result, the deadline for rendering the final award in cases administered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations is three months from the date of referral of the case to the Arbitrator. In 2023, 100% of the final awards in cases administered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations were rendered within six months of the date of registration.

- The report reveals that the median duration of disputes decided under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations is 6 months from the request for arbitration and 4 months from referral to the Arbitrator.

- By way of comparison, the mean duration of disputes decided under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations is 6,3 months from the request for arbitration and 4,2 months from referral to the Arbitrator.

These statistics demonstrate the efficiency of the SCC’s case administration, with cases under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations typically being referred to the Arbitrator in two months.

Apportionment of costs of arbitration and costs for legal represetation

Legal standard for the apportionment of costs

Parties are jointly and severally liable to the arbitrators and to the SCC for the costs of arbitration (Article 49 (7) SCC Rules), regardless of the outcome of the case. This ensures the SCC is able to pay out directly the arbitrators’ and administrative fees and expenses in accordance with the final award, as well as to recover the costs of arbitration from either or both of the parties in the unlikely event of any deficit.

As to the internal cost liability between the parties, the Decision Maker decides which party will finally bear the costs of arbitration, as well as the costs for legal representation (Article 49 (6) and Article 50 SCC Arbitration Rules), in the absence of any agreement of the parties.

Since 2010, the SCC Rules take a simple and flexible approach to the apportionment of costs and do not contain any express presumption in favour of the loser-pays approach.14 Instead, Article 49 (6) and Article 50 of the SCC Rules provide the Decision Maker with the general authority to apportion costs with the outcome of the case as the primary factor to consider in their decision.

However, the SCC Rules provide the Decision Maker with the flexibility to weigh other factors when deciding who will bear the costs. The SCC Rules state that the Decision Maker should also have regard to other relevant circumstances when apportioning costs. As explained further below, the cases examined reveal that from the outcome of the case as starting point, most Decision Makers are inclined to consider the conduct of the parties as a secondary factor when making their costs decisions.

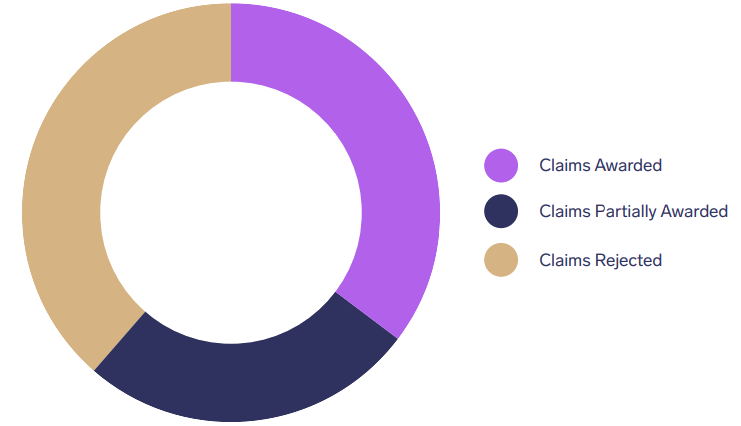

In line with the 2016 report, the 2024 Report has classified the final pool of 221 cases into three different categories depending on the substantive outcome. For the purposes of this 2024 Report, a party’s “success” was measured based on the quantum obtained.

SCC Arbitration Rules

- “Claims awarded” includes 53 cases where the claimant and or counterclaimant was awarded all or almost all of its claims (35%, compared to 46% in the 2016 Report).

- “Claims partially awarded” includes 40 cases where the claimant and or counterclaimant was awarded approximately half of its respective claims (26%, compared to 19% in the 2016 Report).

- “Claims rejected” includes 58 cases in which the claimant and or counterclaimant obtained substantially less than it claimed (38%, compared to 35% in the 2016 Report).

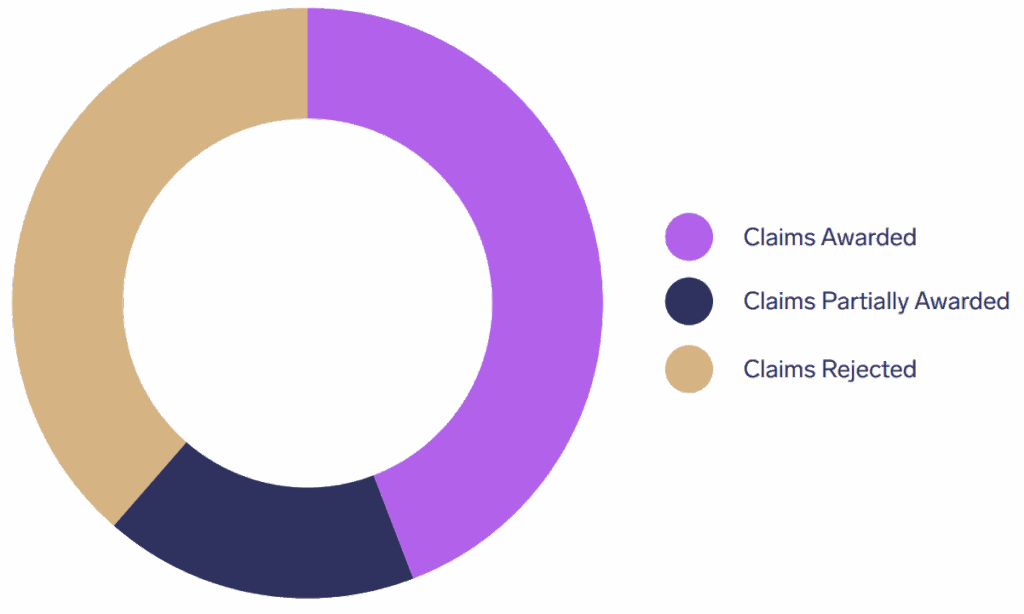

SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations

- “Claims awarded” includes 31 cases (44%) where the claimant and or counterclaimant was awarded all or almost all of its claims.

- “Claims partially awarded” includes 12 cases (17%) where the claimant and or counterclaimant was awarded approximately half of its respective claims.

- “Claims rejected” includes 27 cases (39%) in which the claimant and or counterclaimant obtained substantially less than it claimed.

Apportionment of costs on the basis of the outcome of the case

In arbitral awards rendered under the SCC Rules, the Decision Maker has apportioned the costs in three ways, which the 2024 Report in line with the 2016 Report has categorized as follows.

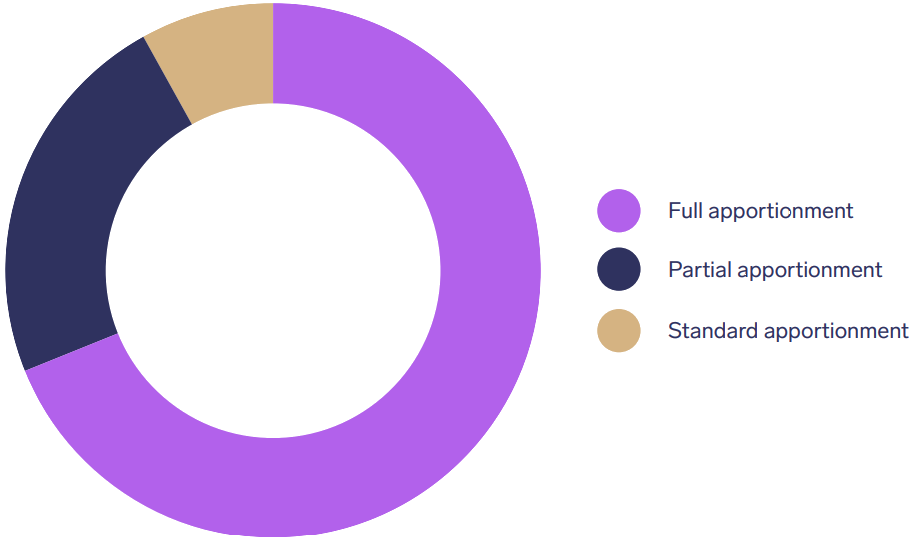

- “Full apportionment”, where one party (usually the unsuccessful party) was ordered to bear all the costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation (69% of cases, 45% in the 2016 Report).

- “Partial apportionment”, where costs were apportioned based on the relative success of the parties, and one or both parties were ordered to bear part of the costs of the arbitration and costs for legal representation in a proportion that mirrors each party’s relative success (23% of cases, 34% in the 2016 Report).

- “Standard apportionment”, where the parties were ordered to bear the costs of arbitration in equal shares and to bear their own costs for legal representation and other expenses (8% of cases, 21% in the 2016 Report).

Compared to the 2016 Report, Arbitral Tribunals have ordered full apportionment in significantly more cases, suggesting that increasingly the winner takes it all. This may be in line with findings that arbitral tribunals are in general not “splitting the baby” when it comes to the main claims in dispute.15

Full apportionment

- Decision Makers overwhelmingly order full apportionment when there is a clear winner, and particularly when that winner is the claimant.

The Decision Maker ordered full apportionment, instructing a party to bear all the costs of arbitration and all costs for legal representation, in 69% of all cases reviewed (a total of 152).

The report demonstrates that the dominant trend continues to be orders of full apportionment where there is a clear successful or unsuccessful party, with 91% Decision Makers deciding accordingly.

The Decision Maker ordered costs in full either against the unsuccessful respondent (85 cases), or against the unsuccessful claimant (69 cases). Full apportionment was ordered in 6,3% of cases (10 cases) where the claims were partially awarded and there was no clear winner or loser. Possible explanations for the deviation in these cases from the dominant approach (i.e. the shifting of the costs to the respondent, although the respondent was partially successful) may be that the measure of success was not based on the quantum of the claims awarded, but on the basis of the issues decided.

In cases where the claimant prevailed (“claims awarded”), 90,5% of Decision Markers ordered the respondent to bear in full both the arbitration costs and the legal fees, whereas in cases where the respondent prevailed (“claims rejected”), 84,7% of Decision Makers ordering the claimant to bear in full both the arbitration costs and costs for legal representation. Compared to the 2016 Report, this represents a significant improvement in the position of the respondent in recovering its costs where it has been successful.

In cases where the respondent prevailed (“claims rejected”), 7,1% of Decision Makers ordered standard apportionments, ordering each party to bear half the costs of arbitration and bear their own legal costs; when the claimant was the winner, 3,6% of Decision Markers ordered such standard apportionments and 30% of Decision Makers adjusted the costs in proportion to the parties’ percentage of success.

A comparison of the 2016 Report and the 2024 Report indicates that when the claimant is the losing party, Decision Makers are now only slightly more inclined to have regard to other circumstances than merely the outcome of the case in reaching their decisions on the apportionment of costs.

Partial apportionment

- Partial apportionments are the second-most preferred approach of Decision Makers when there is a clear winner

That is, Decision Makers have adjusted the costs order in a proportion that reflected each party’s percentage of success. Compared to the 2016 Report, the 2024 Report demonstrates that Decision Makers have ordered partial apportionment in proportionately fewer cases, 18% (40 in total) down from 34% (27 cases).

In stark contrast to the 2016 Report, the 2024 Report indicates that Decision Makers ordered partial apportionments less frequently in cases where either the claimant or the respondent prevailed in the dispute (7,5% and 16%, respectively, down from 41% and 37%), than in cases where there was no clear winner and claimant’s claims were partially awarded (77,5%, up from 22%).

In cases where claims were partially awarded, the dominant trend continues to be for Decision Makers to order partial apportionment in 58,5% of these cases (compared to 53%), followed by standard apportionment in 22,6% of these cases (compared to 40%), with full apportionment ordered in 18,9% of these cases (compared to 7%).

Standard apportionment

- Standard apportionments are the third-most preferred when there is no clear winner as when the respondent has prevailed.

Compared to the 2016 Report, standard apportionments were issued by Decision Makers in proportionately fewer cases, at 13,2% (20 cases), down from 21% (17 cases). Decision Makers also ordered standard apportionments more often in cases where claims were partially awarded (57%) than in cases where the claims were rejected or in cases where the claims were awarded (up from 47% in the 2016 Report).

In cases where the respondent prevailed (“claims rejected”), 7,1% of Decision Makers ordered standard apportionments, ordering each party to bear half the costs of arbitration and bear their own legal costs. When the claimant was the winner, 3,6% of Decision Markers ordered such standard apportionments.

Decision Makers continued to be more inclined to order each party to bear its own costs when they considered that parties had been more or less equally successful or unsuccessful.

- Compared to the 2016 Report, standard apportionments were less frequent in cases where claims were rejected (28,6% versus 41%), and the respondent was the successful party. However, Decision Makers also ordered standard apportionments less frequently in cases where the claimant was successful (14,3%).

Nationality of arbitrators

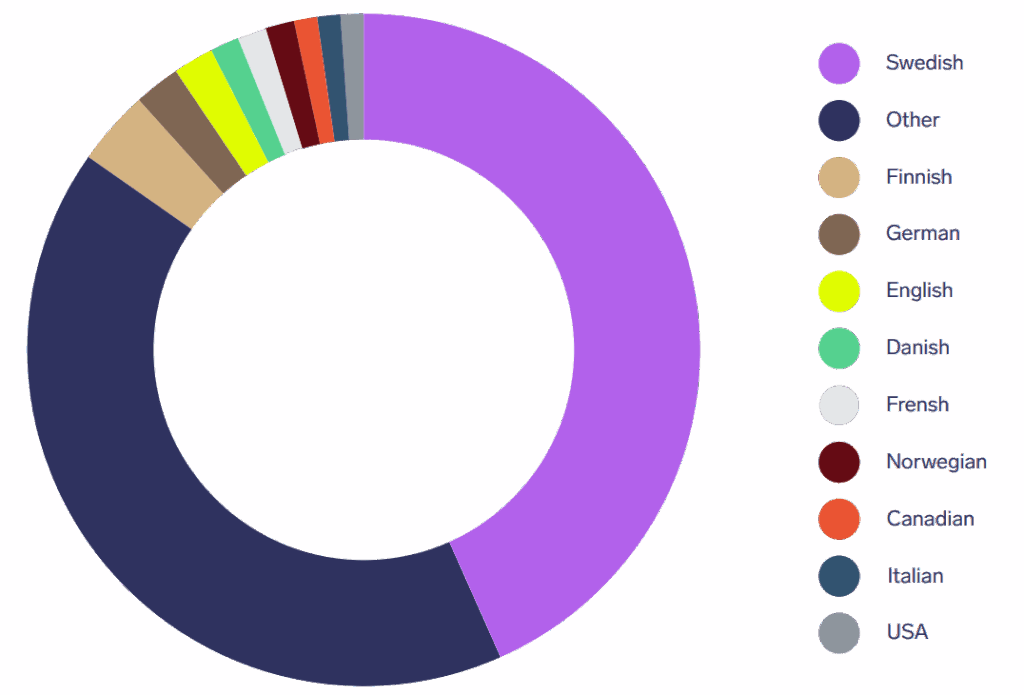

In the period of 2013-2023, which overlaps with both the 2016 Report and the 2024 Report, the arbitrators appointed under the SCC Rules have been comprised of 87 different nationalities.

Compared to the 2016 Report, the 2024 Report demonstrates a significant decrease in the number of Swedish arbitrators appointed under the SCC Rules, resulting in a broader number of nationalities and generally more diverse pool of arbitrators deciding the cases.

- A total of 429 arbitrators were appointed under the SCC Rules to decide these 221 cases, either by the parties, the party-appointed co-arbitrators, or the SCC Board.

- While Swedish arbitrators remain the largest group represented, the breakdown of the top 10 nationalities is as follows:

- Swedish (43,4%) (54,3% in 2016)

- Finnish (3,5%) (7% in 2016)

- German (2,3%)

- English (1,9%)

- Danish (1,4%)

- French (1,4%)

- Norwegian (1,2%)

- Canadian (1,2%)

- Italian (1,2%)

- USA (0,9%) (3,2% in 2016)

- According to the 2024 Report, the remaining 41,6% of arbitrators were of other nationalities from across six continents.

- Of the top five nationalities of non-Swedish arbitrators in 2016, two nationalities have fallen out of the top ten by 2022, Swiss (5,9% in 2016) and Russian (4,3% in 2016).

- The 2024 Report thus demonstrates an increased geographic diversity among the arbitrators appointed under the SCC Rules, reflecting the broader changes in the arbitration market of recent years.

Apportionment of costs on the basis of party conduct

Where the Decision Maker has departed from the general practice of de ciding on the apportionment of costs based on the outcome of the case, the most common consideration when determining the costs recoverable by the successful party was the parties’ conduct during the proceedings, which was cited in 26 cases (11,8%).

In line with the 2016 Report, the 2024 Report indicated the following considerations were identified to adjust the costs recovered by the (relative) winner:

- If the dispute could have been avoided (e.g., it was based on frivolous claims), or whether the claims or counterclaims were legitimate.

- Whether the parties had conducted the arbitration in an efficient manner.

- Whether a party had obstructed or overly complicated the proceedings through, for example, late jurisdictional objections or excessive document requests.

- If a party had refused to comply with the Decision Maker’s orders, or in the case of the respondent, failed to pay the advance on costs.

- Whether much time had been addressed in respect to an issue that was ultimately rejected.

- Whether much time had been spent on issues that had not been properly framed or presented by a party.

- Whether time had been devoted to claims that were later withdrawn.

Pursuant to one newly identified ground, the costs were adjusted as a party had rejected a settlement offer greater than the amount it was ultimately awarded. In that case, the Arbitral Tribunal consisting of a sole arbitrator (non-Swedish) acknowledged that the respondent has made a settlement offer exceeding the amount awarded to the claimant, justifying the adjustment. Thus, and in accordance with the SCC Rules, Decision Makers are having regard to the outcome of the case, each party’s contribution to the efficiency and expeditiousness of the arbitration and any other relevant circumstances.

Awarding costs for legal representation

The parties claimed for their respective legal costs in all 221 cases reviewed for this 2024 Report.

As stated above, when considering specifically the costs of legal representation, in cases where the claimant prevailed in all or almost all of its claims, i.e. in 136 cases or 61,5% of all reviewed cases, the claimant was awarded compensation in full for the costs of its legal representation in 86 cases, or 63,2% of these cases.

In cases where the respondent prevailed in its defence, i.e. in 86 cases or 38,9% of all reviewed cases, the respondent was awarded compensation in full for the costs for legal representation in 72 cases, or 83,7% of these cases.

When determining whether to award costs for legal representation, Decision Makers have in several (eight) cases reduced the amount awarded for the costs for legal representation on the basis that the party’s cost statement was considered not entirely reasonable. However, exact statistics cannot be extracted as a breakdown of such costs awards is rarely provided.

Considerations of Decision Makers when adjusting the costs for legal representation

The most common factor in adjusting the legal costs recoverable by each party was the reasonableness of the costs claimed.

Decision Makers have taken different approaches in respect to the reasonableness of the expenses incurred by a party for costs for legal representation. While the analysis of the 221 cases does not indicate any dominant trends, certain factors commonly considered by Decision Makers in assessing whether claimed costs were reasonable include:

- The fees claimed by the counterparty. When the costs incurred by one of the parties are considerably higher (twice or more), Decision Makers use their discretion to reduce the higher costs.

- The work devoted to each issue, the length and complexity of the dispute. Decision Makers have assessed the reasonableness of the parties’ costs claims in consideration of the complexity of the subject matter, the time spent discussing specific issues in the dispute, or the actual contribution that the costs incurred had in resolving the dispute.

- The parties’ procedural burdens.

- Burdensome, unfounded or unnecessary requests, including requests for document production characterized as unnecessary, changing of counsel at a late stage, or the late withdrawing claims.

- Costs not sufficiently evidenced or justified by a party.

Conclusions

The 2024 Report confirms that under the SCC Rules, the outcome of the case remains the main factor when determining the apportionment of costs. Decision Makers overwhelmingly order full apportionment when there is a clear winner, and particularly when that winner is the claimant.

The proportion of orders of full apportionment have increased.

Partial apportionments are the second most preferred approach of Decision Makers when there is a clear winner.

Standard apportionments are increasingly less common.

However, it is clear from the 2024 Report that Decision Makers continue to adopt different approaches to measure a party’s success. Some Decision Makers look at the quantum of claims awarded, while others prefer making a thorough claim-by-claim analysis, and still others take a more general approach concerning the importance of the main issues in which a party prevailed.

Aside from the outcome of the case, a secondary factor in the apportionment of costs has continued to be the conduct of the parties. Decision Makers see the conduct of the parties among the “relevant circumstances” to consider when finally deciding cost liability between the parties in accordance with the SCC Rules. Examples include frivolous claims, obstruction of the proceedings, unnecessary requests for document production, late jurisdictional objections, and changes of counsel late in the proceedings.

Decision Makers also continue to take into account whether the legal fees claimed are justified in the context of the procedural issues at stake. For example, engaging foreign counsel in a domestic dispute may be considered reasonable insofar as issues of foreign law are relevant, but when they are not, Decision Makers may refuse to award such legal costs.

Decision Makers have aimed to maintain an economic balance in the proceedings. For example, where costs claims are disproportionate compared to those of the counterparty, these may be considered unreasonable

and thus not recoverable.

Based on the 221 cases analysed for this 2024 Report, there is increasing diversity among the nationalities of the arbitrators appointed in SCC arbitrations.

As stated above, the aim of the 2024 Report was to provide an update on the 2016 Report, providing fresh data on the size of disputes, their duration, and costs, as well as how Decision Makers have ultimately apportioned the costs of arbitration and costs for legal representation in order to compare and draw conclusions in respect to arbitrations conducted under the SCC Arbitration Rules.

In comparing the 2016 Report and the 2024 Report, it is possible to make the following conclusions

- The proportion of costs for legal representation of the overall of arbitration in cases administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules appears to have substantially increased, particularly in cases where the Arbitral Tribunal was comprised of three arbitrators. This reinforces the conclusions of the 2016 Report, that the costs of arbitration constitute only a relatively small proportion of a party’s overall costs, that the parties have significant ability to influence the total costs by choosing the most appropriate rules for their dispute as well as the right legal counsel, and that arbitration under the SCC Arbitration Rules remains a cost-efficient method of dispute resolution.

- Moreover, according to the 2024 Report, the duration of cases under the SCC Arbitration Rules has visibly decreased. This further reinforces the conclusion that arbitration under the SCC Arbitration Rules remains a time-efficient method of dispute resolution. At the same time, the amounts in dispute have on average slightly increased in comparison to the 2016 Report.

- Decision Makers have significantly more frequently ordered full apportionment. The dominant trend towards Decision Makers ordering the full apportionment of legal costs for a successful party, and in particular the claimant, has continued. This may be in line with findings that arbitral tribunals are in general not “splitting the baby”.

- Decision Makers have ordered partial apportionments less frequently in cases where one party has prevailed in the dispute, but significantly more frequently in cases where the claimant’s claims were partially awarded.

- Decision Makers have ordered standard apportionments less frequently, but slightly more often where claims were partially awarded.

- The 2024 Report indicates that proportionately fewer Swedish arbitrators are being appointed in favour of a broader pool of arbitrators.This demonstrates the inroads being made in line with the SCC’s ongoing commitment to increasing diversity in arbitration.

- Given the inclusion of the costs decisions in arbitral awards rendered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, there is an increase in the number of domestic, i.e. Swedish cases represented in the data. A further possible reason for this uptick may be an increased harmonization in the practice of arbitration, which has influenced the orders for apportionment of costs by Decision Makers in domestic cases, which in turn has resulted in a greater number of awards forming the basis of the 2024 Report.

The 2024 Report has also for the first time provided data on disputes administered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations concerning the costs of arbitration and apportionment of costs by Decision Makers. Some general conclusions include:

- There appears to have been a greater uptake of the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations among Swedish parties. This may in part be due to a greater awareness in Sweden of the SCC Rules, and uptake of the SCC’s combination clauses, and thus more experience of the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations in practice.

- This imbalance also reflects the increasing number of arbitrations initiated under the SCC’s so-called combination clauses, and in which the Board ultimately decides which of the SCC Rules shall apply, and on the number of arbitrators in the case of the SCC Arbitration Rules. The majority of these to date has been domestic.

- Of the 70 qualifying cases administered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, 25 (36%) were requested on the basis of one of the SCC’s combination clauses, with the vast majority of these invoked clauses (88%) provided the SCC Board with the discretion to determine the rules based on the circumstances of the case. The remainder (12%) applied a monetary threshold.

- Awards rendered under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations have in general closely followed the strict deadlines applicable, demonstrating the clear time and cost-effectiveness of the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations in practice.

As the 2024 Report demonstrates, the costs of arbitration in cases administered under the SCC Rules have in comparison to the 2016 Report significantly decreased as a proportion of the total cost. This indicates that the SCC Rules and arbitration “the Swedish way” continue to be market-leading in ensuring efficiency and efficacy in arbitration for its users. Moreover, it is clear the SCC provides an appropriate forum for arbitrations of varying size and complexity.

The 2024 Report further reinforces the 2016 Report’s conclusions that most of the costs incurred are within the parties’ control. The parties have significant ability to influence the total costs by choosing the most appropriate rules for their dispute as well as the right legal counsel. Parties may then negotiate appropriate fee structures with their legal counsel in order to limit costs.

The SCC will continue to monitor the issue of costs and where possible enhance confidence and transparency in arbitration to ensure a better process, value for users, and an appropriate level of remuneration for arbitrators. This careful balance ensures the maximizing of efficiencies of time, cost, and quality in SCC cases.

About the authors

This report was prepared by Jake Lowther, Specialist Counsel, Lorenzo Nizzi, former Visiting Professional, and Samuel Hörberg Delac, former Research Intern, of the SCC Arbitration Institute. It is an update of the report “Costs of arbitration and apportionment of costs under the SCC Rules” prepared by Celeste E. Salinas Quero, former Legal Counsel of the SCC Arbitration Institute, in February 2016.

Notes

1 Jake is a dual-qualified lawyer (Australia & Sweden) and Specialist Counsel at the SCC. Lorenzo is an Italian jurist and former Visiting Professional at the SCC. Samuel is a former Research Intern at the SCC.

2 The 2016 Report is available here: https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/costs-of-arbitration_scc-report_2016.pdf

3 For further information, see the SCC website here: https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/news/higher-fees-for-arbitrators-from-1-january-2024/

4 SCC, SCC Express.

5 I.e., including SCC cases administered under the SCC Arbitration Rules, the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, the UNCITRAL rules, the SCC Mediation Rules, under Appendix II of the SCC Rules (Emergency Arbitrator), and the SCC’s other services.

6 For further information, see the SCC’s website here: https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/dispute-resolution-clauses/dispute-resolution-clause-english.

7 See the SCC website here: https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/our-services/cost-calculator.

8 The median value of the Arbitral Tribunal’s fees, the SCC’s administrative fee, and the costs of legal representation paid in cases under the SCC Arbitration Rules in disputes decided by a sole arbitrator were compared. It should be noted that median values may not add up to 100%.

9 The median value of the Arbitral Tribunal’s fees, SCC fee and costs of legal representation paid in cases under the SCC Arbitration Rules in disputes decided by three arbitrators were compared.

10 According to Article 11 of the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations, after receiving the answer, and prior to the appointment of the Arbitrator, the SCC may invite the parties to agree to apply the SCC Arbitration Rules with either a sole or three arbitrators, having regard to the complexity of the case, the amount in dispute and any other relevant circumstances.

11 For further information, see the SCC’s website here: https://sccarbitrationinstitute.se/en/dispute-resolution-clauses/dispute-resolution-clause-english.

12 It should be noted that median values may not add up to 100%.

13 The median value of the Arbitrator’s fees, SCC fee and costs of legal representation paid in cases under the SCC Rules for Expedited Arbitrations disputes were compared.

14 Cf. Article 41 “Costs Incurred by a Party” of the 1999 SCC Rules, which provided: “Unless the parties have agreed otherwise, the Arbitral Tribunal may, at the request of a party, in an Award or other order by which the arbitral proceedings are terminated, order the losing party to compensate the other party for legal representation and other expenses for presenting its case.”

15 See, e.g., Ana Carolina Weber, Carmine A. Pascuzzo S., et al., “Challenging the ’Splitting the Baby’ Myth in International Arbitration”, Journal of International Arbitration, (Kluwer Law International 2014, Volume 31 Issue 6) pp. 719-734; Stephanie E. Keer and Richard W. Naimark, “Arbitrators Do Not ‘Split the Baby’ – Empirical Evidence from International Business Arbitrations”, 18(5) Journal of International Arbitration, (2001) 573.